Do we get the spark of rapture for any work of art from elements resurrected from our own memories?

The playwright, Tennessee Williams described a memory play as a story that unfolds from the perspective of a major character. It’s a wonderful phrase that can be extended to the viewer of visual art, opening up the idea that what any of us “see” may come from what we can bring from our past experiences. This process is, of course, subjective, and frequently hard to put into words; the effects of images are not always converted into ordinary language. But we may still encounter feelings and attitudes we already know. Form in representations of the the body or a face, or of an image’s setting and colors may trigger resonances we welcome back to our consciousness.

The playwright, Tennessee Williams described a memory play as a story that unfolds from the perspective of a major character. It’s a wonderful phrase that can be extended to the viewer of visual art, opening up the idea that what any of us “see” may come from what we can bring from our past experiences. This process is, of course, subjective, and frequently hard to put into words; the effects of images are not always converted into ordinary language. But we may still encounter feelings and attitudes we already know. Form in representations of the the body or a face, or of an image’s setting and colors may trigger resonances we welcome back to our consciousness.

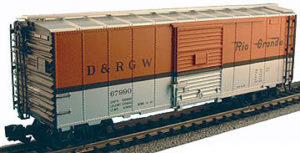

The question came up because I get asked what I “see” in the few old model railroad boxcars I collect. They are about 18 inches long. I’m tempted to say that I thought everyone had these in their living room. But—following a train of thought here—the straight answer is that they surely revisit some of the same synapses I experienced as a child crossing through the extensive rail yards in Denver. The steel behemoths were lined up for blocks, the colorful livery designs representing different railroads untouched by graffiti scribblers. Any kid in the west growing up in the middle of the last century was primed to see railroads as the transformative force reshaping the plains. These imposing lines of wheels and metal somehow became my own totems.

To be sure, children then would have to be older to learn the dreadful consequences of what all this westward expansion meant for indigenous people. But the broader point remains: do we get the spark of rapture for any work of art from elements resurrected from our memories?

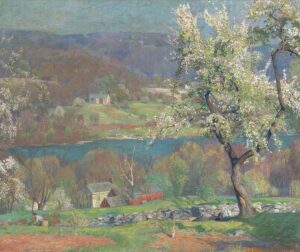

I have a sense this process is why many of us respond positively to the lush landscapes of Georgia O’Keefe, Thomas Cole or Daniel Garber. To view many of their works is to revisit attributes of place that have stayed with us. Most have been fortunate to have experienced their subjects of big skies, lush lakes and forests, or vast open spaces.

Abstract expressionists and the sometimes-dreary avant-garde of the art establishment have moved on from the representative style of these older painters. But even the colored boxes and neat lines of a Mondrian can probably trigger associations—conscious or not—bubbling up from obscure experience.

Does it matter if art is another version of a memory play? Perhaps not. But self-aware artists may recognize in their own visual rhetoric echoes of impressions they already know. In the maw of a churning culture their private resource is transformed into forms that trigger different pleasures in others.

![]()