In true debates, the press simply listens like the rest of us. In an authentic debate there may be moderators, but not questioners.

The political season always brings out a cycle of “debates” finally agreed to by cautious candidates and news organizations. Though everyone involved has different motives, the one most commonly expressed is that these events offer the public the chance to compare candidates side by side. In the unfettered give-and-take of a debate we are supposed to learn about issues that divide or maybe even unify those running for the same office.

Even so, most of these joint appearances fall short in testing persons and ideas. As usually formatted, they can’t achieve these lofty goals, for two reasons. First, the response times for individuals are always too short, often a minute or less. Bernie Sanders is right to call them “demeaning.” And second, for no valid reason the press wants in on the action as well. The quid pro quo is free airtime, if they can be part of the show.

Even so, most of these joint appearances fall short in testing persons and ideas. As usually formatted, they can’t achieve these lofty goals, for two reasons. First, the response times for individuals are always too short, often a minute or less. Bernie Sanders is right to call them “demeaning.” And second, for no valid reason the press wants in on the action as well. The quid pro quo is free airtime, if they can be part of the show.

Ideally, debates should deliver what philosophers call “dialectic:” a purposeful clash of views where claims and evidence are tested against a series of counter-arguments. Among others, Aristotle was certain that acts of public advocacy had a cleansing effect on the body politic. He believed we are wiser for subjecting our ideas to the scrutiny of others. This may sound lofty and abstract, but most of us do a form of this when we talk through a pending and important decision. We often want friends to help us see potential problems in a planned course of action.

In open societies such as ours we expect to hear contrasting opinions. It’s a wonderful process when it’ well-formatted. Otherwise—and as devised by most political operatives—a political debate is usually is little more than a joint press conference.

The candidates share part of the blame. They usually fear these exchanges. They and their staffs believe that a serious gaff can sink an entire campaign. So they hedge their bets. They agree to “debates” if they are moderated by a panel or at least a single journalist. The logic of journalism is to ask new questions at frequent intervals. This is when the process begins to go south. It’s further doomed when each side is given only a minute or so to respond. These errors are then compounded with a final counter-response that is barely the length of a sneeze. As it now exists, it’s little more than a lukewarm form of political theater.

A good debate will have no more than a moderator or time-keeper to equalize participation and keep things civil. The advocates directly address the claims and arguments of their opposites on what is usually a single broad but important subject area. Their opening remarks must be permitted to be longer than a television commercial. They then listen, refute, question, and challenge each other. When one issue seems to have been exhausted, the moderator may steer the pair to a related issue and then get out of the way.

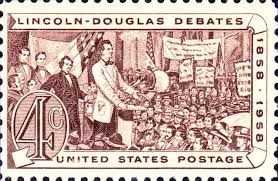

Lincoln and Douglas debated for hours by themselves without the assistance of others. Indeed, a prime form of Saturday night entertainment in the nineteenth century was a formal debate in a town’s biggest venue. The whole process of seeing two leaders explain their ideas under the scrutiny of an interested audience could be invigorating. By contrast, the short question-based formats commonly in American political debates generally ruin the chance to see how much a candidate truly knows, beyond the memorized sound bites that they repeat at every stop. Just when follow-up rebuttals might begin to test a candidate’s knowledge of an issue, the questioners usually interrupt and move on to a new topic.

Lincoln and Douglas debated for hours by themselves without the assistance of others. Indeed, a prime form of Saturday night entertainment in the nineteenth century was a formal debate in a town’s biggest venue. The whole process of seeing two leaders explain their ideas under the scrutiny of an interested audience could be invigorating. By contrast, the short question-based formats commonly in American political debates generally ruin the chance to see how much a candidate truly knows, beyond the memorized sound bites that they repeat at every stop. Just when follow-up rebuttals might begin to test a candidate’s knowledge of an issue, the questioners usually interrupt and move on to a new topic.

Several years ago Americans could catch a series of debates in the United Kingdom between Alistair Darling and Alex Salmond on Scotland’s referendum to go it alone as an independent nation. Scotland ultimately voted to stay: an outcome that might not hold these days, given their current displeasure with London’s intention to leave the E.U.

The original debates weren’t perfect by any means. But these televised clashes had the advantage of allowing both sides sufficient time to make essential arguments and extended refutations. As can be seen with the never-ending Brexit debate, the British expect that members of the government and individual M.P.s will be able to stand up under sometimes challenging counter-arguments from their ideological opponents.

Debates should extend beyond glib assertions of support or opposition. In the United States we rarely let candidates go on long enough to discover if they have confronted the full consequences of their positions.

![]()