[Forbearance is sometimes the best policy. It’s common to respond to every provocation. It’s even easier since our retorts can often be anonymous. But as this 2014 post notes, there is a degree of grace in letting a misguided view pass without a response]

[Forbearance is sometimes the best policy. It’s common to respond to every provocation. It’s even easier since our retorts can often be anonymous. But as this 2014 post notes, there is a degree of grace in letting a misguided view pass without a response]

In the age of Trump every verbal action seems to trigger a response. Judgments are easy and somehow self-affirming. It is always tempting to think that we are being helpful when we explain to the misguided how they have failed to notice their mistakes. Since others offer corrections or criticisms of our ideas or acts; the least we can do is return the favor

Aristotle was one of the first to systematically describe how a person should defend their ideas when challenged. He equated the ability to make counter-arguments as just another form of personal defense. Though the great philosopher used other words, he essentially noted that we shouldn’t allow ourselves to be pushed around. This was about 380 B.C., demonstrating that some things never change.

Even so, it has perhaps become too easy to fire off a rejoinder or a personal attack. Most of us find it hard to be in a public space and not encounter cross-court slams from an ideological opponent that seem to need an equally aggressive return.

The digital world easily brings our indignation to the fore. Many websites welcome comments, the majority of which are misguidedly protected with anonymity. And it isn’t just the trolls that are rattling on about a writer’s sloppy logic or uncertain parentage. In private and public settings everyone seems to be ready with a hastily assembled attitude. The felicitous put-down is so common that screenplays and narratives seem to wilt in their absence. What dramatist could write a scene about a family Thanksgiving dinner without including at least a couple of estranged relatives rising to the bait of each other’s festering resentments? To make matters worse, some of us actually get paid to teach others how to argue, with special rewards going to those who are especially adept at incisive cross examination.

There are many circumstances when the urge to respond is worth suppressing. Sometimes saying nothing is better than any other alternative: less wounding or hurtful, or simply the best option in the presence of a communication partner who is out for the sport of a take-down.

The psychological rewards are overrated.

Even a brilliant rejoinder is not likely to force an errant advocate back on their heels. You may be itching to correct them. But they are probably determined to ignore you.

And there are costs to becoming shrill. Harry Truman famously sensed this. The former President had a hot temper. Even before he was elected he had more than his share of critics. But his approach to responding to criticism made a lot of sense. In the days when letters often carried a person’s most considered rebuttals, his habit was to go ahead and write to his critics, often in words that burned with righteous indignation. But he usually didn’t mail them. The letters simply went into a drawer, which somehow gave Truman the permission to move on to more constructive activities, such as a good game of poker.

Not responding to someone else’s provocative words can have at least two advantages. The first is that your comments probably won’t be received anyway. We tend to ignore non-congruent information, a process known in the social sciences as “confirmation bias,” but familiar to everyone who has ever said that “we hear only what we want to hear.” The second advantage is that rapid responses to others can carry the impression that the responder lacks a certain grace. Not every idea that comes into our heads is worth sharing. In addition, fiery replies sometimes indicate that we weren’t really listening. Just listen to almost any interview with former New York Mayor Rudolph Giuliani.

Time gives us a better perspective. It allows us to better anticipate how our responses will be judged. Most importantly, it helps us break the cycle where one wounding response is simply piled on to another.

![]()

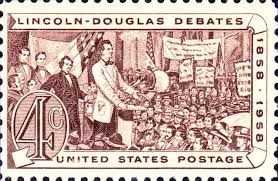

In true debates, the press simply listens like the rest of us. In an authentic debate there may be moderators, but not questioners.

In true debates, the press simply listens like the rest of us. In an authentic debate there may be moderators, but not questioners.

Lincoln and Douglas debated for hours by themselves without the assistance of others. Indeed, a prime form of Saturday night entertainment in the nineteenth century was a formal debate in a town’s biggest venue. The whole process of seeing two leaders explain their ideas under the scrutiny of an interested audience could be invigorating. By contrast, the short question-based formats commonly in American political debates generally ruin the chance to see how much a candidate truly knows, beyond the memorized sound bites that they repeat at every stop. Just when follow-up rebuttals might begin to test a candidate’s knowledge of an issue, the questioners usually interrupt and move on to a new topic.

Lincoln and Douglas debated for hours by themselves without the assistance of others. Indeed, a prime form of Saturday night entertainment in the nineteenth century was a formal debate in a town’s biggest venue. The whole process of seeing two leaders explain their ideas under the scrutiny of an interested audience could be invigorating. By contrast, the short question-based formats commonly in American political debates generally ruin the chance to see how much a candidate truly knows, beyond the memorized sound bites that they repeat at every stop. Just when follow-up rebuttals might begin to test a candidate’s knowledge of an issue, the questioners usually interrupt and move on to a new topic.