Are we a nation that is still addressable as a national community?

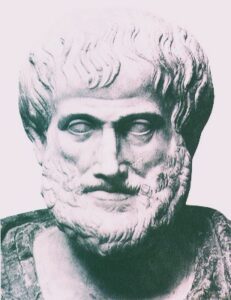

Since the early democracies in Sicily, we have assumed a person or group with a persuasive intent must think of message elements that build on shared attitudes. This idea is a central canon in communication studies. We understand an audience to be the generative source of successful persuasion attempts. As Aristotle noted, It’s from their views that a persuader fashions ways to connect with them. If I want to be elected to the city council, I must have the assent of the community who can vote yea or nay. They must be addressed and satisfied. Dictators in closed societies have other non-rhetorical means for gaining compliance.

We still lean heavily on the belief that we can lump individuals together in cohesive groups with demographic and attitudinal similarities, fashioning an acceptable message that draws from their views. Traditional media outlets such as television networks often “sell” their audiences to advertisers based on some of these features. And virtually every music, film and television producer is convinced they know their “market,” which is presumably a ‘market of shared values and ideas’ as much as anything else.

Even so, the concept of the audience rarely works as well in fact as it does in theory. In their study of The Mass Audience (1997), James Webster and Patricia Phalen remind us that “audiences are not naturally occurring ‘facts,’ but social creations. In that sense, they are what we make them” We imagine their similarities with us, or at least our shared views of how the world works.

There are two problems with this core idea the audience. One is that with the proliferation of media choices contained in the internet turn out to gather together neither uniform nor very predictable audience types. Even the motives of those who self-select themselves into the same group can be surprisingly diverse. For example, it would be risky to infer much about the audience for content that has identified as part of a Facebook group. Having a shared interest sometimes tells us less than we think. Even analysts at Nielsen Media Research—the nation’s venerable audience research firm—would concede that it’s extremely difficult to come up with meaningful metrics especially for most media sites.

The second problem is even more daunting. The structural changes in our more dominant social media make individual usage scattered and fragmented in ways that are hard for anyone to know. Aristotle wrote one of the first studies of human communication (The Rhetoric, circa 335 BC) with an eye on the challenges of addressing a few hundred citizens within a small city. Today, by contrast, audiences are sometimes defined in the millions, with messages delivered to them on a host of platforms that increasingly muddle the question of what makes a message visible or likeable. Algorithms can put individuals in line to receive a particular message. These are ostensibly extensions of metrics identified by a person’s known media and consumer habits. But how message bits “play” with a receiver is still hard to predict.

The second problem is even more daunting. The structural changes in our more dominant social media make individual usage scattered and fragmented in ways that are hard for anyone to know. Aristotle wrote one of the first studies of human communication (The Rhetoric, circa 335 BC) with an eye on the challenges of addressing a few hundred citizens within a small city. Today, by contrast, audiences are sometimes defined in the millions, with messages delivered to them on a host of platforms that increasingly muddle the question of what makes a message visible or likeable. Algorithms can put individuals in line to receive a particular message. These are ostensibly extensions of metrics identified by a person’s known media and consumer habits. But how message bits “play” with a receiver is still hard to predict.

Market “insights” can be notoriously prone to failure, as a recent ad for Apple iPads demonstrated. Buyers of Apple products want to be known as hip, edgy, and ready to change the natural order of things. . . . Except when they are not. The bright lights designing Apple’s introduction to their new iPad forgot their core audience includes a lot of creative people. In fact, rarely has a company heard so quickly that they missed the mark, as Tim Cook later admitted. They misjudged the regard their audience surely felt for various tools of the arts that the company so gleefully trashed in their ad. Frankly, its an unintended horror movie. Take a look.

Beyond our love of mass market films and major social media sites like Instagram, do we share anything like the common civic culture that was easier to see in the pre-digital age? Maybe general revulsion to this ad says yes. But if modern life now proceeds as continuous exposure to a series of visual riffs in broad-based and space-restricted media such as U-tube or Google Plus+, is there any chance to create a series of appeals can consistently speak to their heterogeneous users?

All of these concerns may appear rather abstract. But they have real consequences. We traditionally assume that effective messages usually get their energy from appeals that trigger a sense of identification with a source and their message. We also assume that communication failure can often be attributed to messages that have “boomeranged,” meaning a piece of discourse has actually alienated those who received it. But, of course, you have to care about the effects of your words. So a fading tradition that assumes our words are chosen to match the needs of a given audience raises practical questions about whether enough Americans have the will to function in a society that coheres.