Shakespeare gave his audiences fair warning about advancing age and the risks of clinging to power. By the end of the play, King Lear is old and crazy, with his dominion in chaos.

There’s a lot of discussion in the popular media about political leaders who have stayed in power too long. Our recent history with Joe Biden at age 82 and Donald Trump at 79 are the most recent cases of apparent declines in mental stamina, though, in Trump’s case, the evidence is decidedly mixed. Incompetence and dementia can look like the same thing. There is also the example of Mitch McConnell (83) in the Senate, who appears to not have had the good graces to step down when he could keep track of his thoughts. Senator Diane Feinstein of California was incapacitated before she died at 90, and the District of Columbia’s Eleanor Holmes Norton seems to be suffering through the same frailty. On the whole, these cases and others like them feed a cultural norm of impatience with those still in power and showing unusual longevity.

Interestingly, and as a matter of policy, the Church of the Latter-Day Saints picks their oldest elder to be their leader. Dallin H. Oaks will start his term to lead the church at the age of 93, one year older than the recently elected President of the central African state of Cameroon. By contrast, many commercial airline pilots must retire at the comparatively young age of 65. And surgeons are mostly done by age 70. But just when a trend seems clear, someone like Bernie Sanders (84) comes along, exciting the young with his articulate and impassioned rebukes of his Senate colleagues and Donald Trump. Sanders is an example for arguing that “age is just a number.” And there is the special case that is New York City, which has just elected 32-year-old Zohran Mamdani as mayor. By comparison, and with some exceptions, many of Sander’s colleagues in Congress–most in their 60s or older–lack the inclination or stamina to be effective legislators.

Interestingly, and as a matter of policy, the Church of the Latter-Day Saints picks their oldest elder to be their leader. Dallin H. Oaks will start his term to lead the church at the age of 93, one year older than the recently elected President of the central African state of Cameroon. By contrast, many commercial airline pilots must retire at the comparatively young age of 65. And surgeons are mostly done by age 70. But just when a trend seems clear, someone like Bernie Sanders (84) comes along, exciting the young with his articulate and impassioned rebukes of his Senate colleagues and Donald Trump. Sanders is an example for arguing that “age is just a number.” And there is the special case that is New York City, which has just elected 32-year-old Zohran Mamdani as mayor. By comparison, and with some exceptions, many of Sander’s colleagues in Congress–most in their 60s or older–lack the inclination or stamina to be effective legislators.

Shakespeare could have easily imagined the enfeebled American nemisis, King George III, who was 81 when he died. Today, some of Britain’s senior leaders end up in the House of Lords, which has a ceremonial and advisory role in governmental affairs. We have no equivalent of a body of wise old men and women who can apply their experience to intractable national problems. That’s too bad because there are leaders from both parties who could help shape some constructive paths forward for the nation. Easing out President Nixon in 1974, after the Watergate coverup, was arguably easier because of the presence of senior members in both parties who convinced him that it was time to go.

Joe Biden’s struggles to remain alert and coherent were evident at the end of his presidency. Perhaps that is one reason so many Americans are primed to consider whether Trump is able to process information and ideas and, more tellingly, to perform the very presidential necessity of staying on point throughout a presentation. Sadly, even less than a year into his administration, some of his constituents and his counterparts in other nations no longer view him as having the character needed to be a reliable partner. The General Services Administration will want to count the silverware when he finally leaves the public housing we mistakenly assumed he would leave in tact.

I have sympathy with younger Americans who claim that the nation’s leadership should be in the hands of more nimble minds. There is a lot of grumbling about “boomers” my age who have ostensibly damaged accesibility to the American dream. Did we give our children too much? Did we grow too isolated and materialistic? Have we sentimentalized the accumulation of wealth at the expense of more universal values? And have we allowed our media to be turned into wall-to-wall distractions that diminish real life experience?

I have sympathy with younger Americans who claim that the nation’s leadership should be in the hands of more nimble minds. There is a lot of grumbling about “boomers” my age who have ostensibly damaged accesibility to the American dream. Did we give our children too much? Did we grow too isolated and materialistic? Have we sentimentalized the accumulation of wealth at the expense of more universal values? And have we allowed our media to be turned into wall-to-wall distractions that diminish real life experience?

All of these questions are timely. On the other hand, it is easy to be disappointed to discover that many current protesters responding to Trump administration policies are much older than youthful activists in the 1960s. Protests against Isreal on college campuses are an exception. But I have attended recent rallies and marches against Trump-era policies where the age of the average attender seems to be on the far side of 60. That is not going to cut it if we are going to renew this society.

Watching President Biden manage his presidency, I am impressed at how disciplined he is in not answering all of the criticisms that come his way. As a senator he was not always a study in forbearance. And he could showboat. But perhaps age and the burdens of managing an impossible federal bureaucracy have fed a clear desire to keep his focus on the bigger issues he has tried to manage. He gets too little credit for successes in reshaping immigration practices on the southern border, doing what he can to stabilize inflation, becoming a predictable ally to our friends, and bringing some industrial jobs back to the U.S. No doubt he frustrates conflict-loving media, who would like nothing better than clips of snappy presidential retorts. He is not particularly good copy, at least compared to his two predecessors. But as an older man, he has freed himself from testosterone-fueled rage that so many in politics seek to display. Age has its virtues. It is a disappointment that more Americans can’t see them.

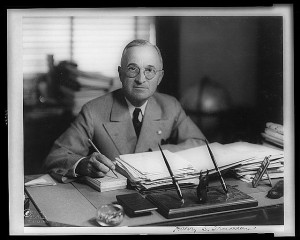

Watching President Biden manage his presidency, I am impressed at how disciplined he is in not answering all of the criticisms that come his way. As a senator he was not always a study in forbearance. And he could showboat. But perhaps age and the burdens of managing an impossible federal bureaucracy have fed a clear desire to keep his focus on the bigger issues he has tried to manage. He gets too little credit for successes in reshaping immigration practices on the southern border, doing what he can to stabilize inflation, becoming a predictable ally to our friends, and bringing some industrial jobs back to the U.S. No doubt he frustrates conflict-loving media, who would like nothing better than clips of snappy presidential retorts. He is not particularly good copy, at least compared to his two predecessors. But as an older man, he has freed himself from testosterone-fueled rage that so many in politics seek to display. Age has its virtues. It is a disappointment that more Americans can’t see them. President Harry Truman also sensed the high costs of becoming shrill. The former President had a hot temper. Even before he was elected, he had more than his share of critics. But his approach to not publicly respond to criticism made a lot of sense. In the days when letters often carried a person’s most considered rebuttals, his habit was to go ahead and write to his critics, often in words that burned with righteous indignation. But he usually didn’t mail them. The letters simply went into a drawer, which somehow gave Truman permission to move on to more constructive activities, such as a good game of poker.

President Harry Truman also sensed the high costs of becoming shrill. The former President had a hot temper. Even before he was elected, he had more than his share of critics. But his approach to not publicly respond to criticism made a lot of sense. In the days when letters often carried a person’s most considered rebuttals, his habit was to go ahead and write to his critics, often in words that burned with righteous indignation. But he usually didn’t mail them. The letters simply went into a drawer, which somehow gave Truman permission to move on to more constructive activities, such as a good game of poker.