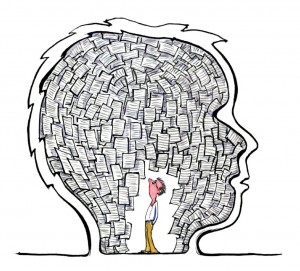

We our own islands of consciousness, forever separated from others. We may share the substrate of a common culture and lineage, and we can build bridges to each other, but we can never fully inhabit another’s unique psychological space.

Climate scientists warn that it will be just decades until areas of South Florida will become a watery archipelago. The level of the sea rises about one inch a year in Miami Beach, inundating streets that some residents continue to believe are flooded by water main breaks. Even in denial, they must sense that a chain of islands makes continuous connection with the rest of the community an insurmountable problem.

Interestingly, in the last six years communication scholar John Durham Peters has eloquently made the same observation about human communication (Speaking Into the Air, 1999). We are, he says, our own islands of consciousness, forever separated from others. We may share the same substrate of a common culture and lineage, and we can build bridges to each other, but we can never fully occupy the adjoining person’s world. His analysis turns the iconic lines of John Donne’s prose poem literally and figuratively on its ear.

All of this is Peters’ way of reminding us that we have oversold our abilities to make things right through communication. He notes that problems of connecting with others are “fundamentally intractable.” The goal of doing so creates a “registry of modern longings” that can never be fully satisfied. Disappointment is a natural part of the effort.

Our sensations and feelings are, physiologically speaking, uniquely our own. My nerve endings terminate in my own brain, not yours. No central exchange exists where I can patch my sensory inputs into yours, nor is there any “wireless” contact through which to transmit my experience of the world to you. . . . In this view, humans are hardwired by the privacy of experience to have communication problems.

Of course the theme of humans physically together and psychologically apart is universal, reflected in everything from Edward Hopper’s lone figures in the painting, Nighthawks (1942), to virtually any film or play that treats individuals and relationships in all of their complexities. The tensions inherent in coupling and adapting are shot through the work of film directors, ranging from Woody Allen to Ang Lee.

This perspective only seems pessimistic if we believe in a kind of communication that is so stipulative or stripped of complexity as to be uninteresting. I can say with great accuracy that the Ketchup in our household is in the refrigerator, and know I can be understood. But who cares? The things that usually matter–feelings, values, aspirations and needs–all feed into making each individual their own special case. Could it be otherwise when we engage with other living souls with different life histories, memories, fears and hopes?

Another part of our common over-optimism about communication is that we have sold ourselves on the belief that advances in technologies are themselves reasons to mitigate communication confusion. Our devices make it possible to talk or text through every waking hour. But, if anything, opportunities for sending and receiving messages only increase the chances to see the differences between us that remain.

The trick here is to accept the challenges that human complexity produces without decending into a solipsistic view that the outside world is mostly a mental mirage. To fall into that trap is to deny the ecstasies that are still possible when words, images and music make sometimes durable bridges to others.

Comments: Woodward@tcnj.edu