There is simply no narrative form that is quite as effective as an extended video or film exploration of a complex person or trend.

Our heads are now and too often cast down to small screens so we can read even smaller messages. Sometimes it seems like we are spending our time looking at the equivalents of fortune cookie aphorisms.

We can do so much better. The technology is there. We just have to show an interest.

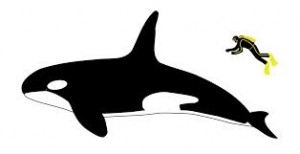

One of the more recent advances in our media is not particularly “digital” at all; it’s the rebirth of the longform documentary focusing on important histories and cultural trends. It’s not an overstatement to note that the culture changed after CNN broadcast Gabriela Cowperthwaite’s 83-minute documentary, Blackfish in 2013. More viewed it when it was distributed as a feature by Magnolia Pictures. Once people saw the trailer they were drawn to the film. Cowperthwaite put the issue of animal abuse front and center at the moment when the topic was at a cultural tipping point.

The prime advantage of most documentaries are that they are inviting entry points into an important narrative. The subject could be popular a single musician, a saga about one family, or our financial system. Diverse subjects have been explored with sensitivities to the people whose dreams have been realized or dashed by mostly systemic pressures that are not visible in shorter narratives. Most are personal; documentary filmmakers understand that their focus needs to be on individuals with stories to tell and tough choices to make. Many have also been trained to structure stories that are coherent even without an off-screen narrator. That was once a novel mode of working, tried by Frederick Wiseman, which has since become the norm.

The longform documentary is sometimes still used by PBS, though they are often more enthusiastic about non-confrontational elements in the natural world. And CBS once had a crack documentary unit headed up by Fred Friendly and Edward R. Murrow, now just a distant memory, but recalled in the feature-length docudrama, Good night and Good Luck (2002). Now it is mostly the larger streaming services and cable services that buy and schedule hard-hitting documentaries. HBO, Showtime and Netflix are examples. To be sure, financing documentaries and selling them is still a rugged and difficult process for a filmmaker, even though shooting can now be done using more economical digital equipment. We can thank a handful of dedicated professionals who have persevered–Alex Gibney, D.A. Pennebaker and Chris Hegedus, Ken Burns, Michael Moore–among many others.

Here are a few favorites that are generally available for streaming and found with a simple Google search:

Working and Workers

- American Factory (2019)

- Roger and Me (1989)

- The Last Truck (2009)

- Last Train Home (2009)

- Harlan County USA (1976)

Music

- Jazz

- Hitsville: The Making of Motown (2019)

- Seymour: An Introduction (2015)

- 20 feet from Stardom (2013)

- Glen Campbell, I’ll be Me (2014)

- Moon Over Broadway (1997)

- The Last Waltz (1976)

- Best Worst Thing That Could Have Happened (2016)

- Woman of Heart and Mind (2003)

Politics, Culture and Society

- Times of Harvey Milk (1984)

- The Inventor (2019)

- Alive Inside (2010)

- Enron: The Smartest Guys in the Room (2005)

- Man on a Wire (2008)

- The Fog of War (2003)

- Sound and Fury (2000)

- Hearts and Minds (1974)

- An Inconvenient Truth (2006)

- Gasland (2010)

- Fyre (2019)

- The War Room (1993)

There is simply no narrative form that is quite as effective as a well-made 90-minute exploration of a topic. We are lucky that the form has never been more accessible.

![]()