-Add in the degraded audio quality of most streaming, MP3 compression, or home-based Bluetooth equipment, and you are suddenly in the cheap seats behind the restrooms–some distance away from what can be heard from a studio master released as a CD

A few years back I wrote a piece about whether we were done collecting books and music. Many people are, but it can be a mistake to abandon those once-loved CDs. What is interesting now is how streaming has come to dominate the music industry. Streaming means you pay a fee to access a vast library service with the music you want to hear. In most cases its incredibly small royalties are a thumb in the eye to musicians, but it is ever so convenient for people who want wall to wall music without having to lift a finger. No collecting required. In 2019 Spotify had become the dominant form of music delivery, with other services like Pandora, radio and YouTube not far behind.

What a different world the music industry was in 1999, when 900 million compact discs were sold. But in the years that followed, the CD lost favor and went into a near total collapse of sales. Suddenly perfect digital copies could be made without additional purchases. By 2007, most of the huge brick and mortar stores like Tower Records and HMV were shuttered, and favorite form of retail therapy died with them. CDs now sell at the modest rate of 31 million copies a year, with Japan the only remaining major consumer. In fact some who study music industry trends in the United States barely notice this superior older format.

As for streaming, what benefits consumers is often a nightmare for performers. Fee-based streaming services put performers at the end of a meager financial food chain that was mostly tapped-out before they were paid. In 2019 the Canadian cellist Zoe Keating reported that her royalty for each stream of her music played by Spotify was $0.0054.

This short essay came to mind after reading a recent article from the Guardian’s Matt Charlton, who wondered if there was any point in holding on to the silver discs that solved many of the problems inherent in vinyl records. Some audiophiles will disagree, but modern CDs can offer stunning sound. They also eliminated the problems created by physically trying to race a stylus through a narrow trough of vinyl. Clicks, pops, inner groove distortion, warping, and washed-out sound from worn down grooves are problems listeners no longer have to contend with. But as Charlton still sees it, CDs “are inherently unlovable, with none of the richness or tactile nature of vinyl, or the kooky, Urban Outfitters irony of tapes.”

This short essay came to mind after reading a recent article from the Guardian’s Matt Charlton, who wondered if there was any point in holding on to the silver discs that solved many of the problems inherent in vinyl records. Some audiophiles will disagree, but modern CDs can offer stunning sound. They also eliminated the problems created by physically trying to race a stylus through a narrow trough of vinyl. Clicks, pops, inner groove distortion, warping, and washed-out sound from worn down grooves are problems listeners no longer have to contend with. But as Charlton still sees it, CDs “are inherently unlovable, with none of the richness or tactile nature of vinyl, or the kooky, Urban Outfitters irony of tapes.”

His reasons don’t add up to much of an argument. Is he serious about the sonically handicapped cassette tapes that were originally designed for dictation? And what about “tactile vinyl” with grooves everywhere that you are not supposed to touch? I also must have missed the concerts at Urban Outfitters. Overall, I’m not feeling the vibe.

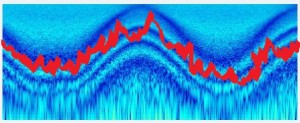

![]()

A CD has the capacity for sound accuracy higher than what Apple, Amazon and other music services are routinely streaming.

In fact, CDs are amazing as carriers of music and its supporting images and texts. The standard sampling rate of 44,000 Hz a second is a phenomenal rate for accurately rendering what microphones have heard (assuming your playback device has a decent digital-to-analogue converter.) This is the big remaining asset of the CD; it has emerged as an easy way to hold on to what avid music listeners call “lossless” sound. That is, a CD has the capacity for sound accuracy far above what Apple, Amazon and other music services are routinely streaming. Add in more degrading streamed audio files like MP3 compression or Bluetooth equipment, and you suddenly only qualify for the cheap seats near the restrooms.

Of course there are some caveats. Many listeners seem to have trained their ears to not care about less-than-optimal sound. And even a well-made CD won’t help what started out as a bad recording. In addition, if smaller cards and memory chips can now hold the same accurate audio content, the CD remains the most accessible medium we have for holding the complete package of music, notes and images that a carefully thought-out album represents. For me, new music starts from a physical CD, a personal “master,” before it is stored somewhere else as a high-quality audio file. What’s not to love about these small silver marvels?

![]()