In this age of distraction many of us don’t notice when we sabotage our own messages.

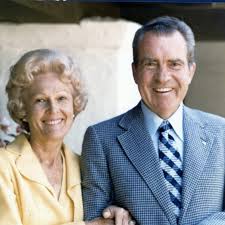

Over a lifetime of language use, if we are paying attention, most of us will notice the ironies and contradictions that so easily creep into our discourse. Some of us are better than others. And, as least in popular culture, even stand-up comedians can be good at zeroing in on pieces of our verbal or visual communication that are at war with other parts of the  same message. Think of the old Woody Allen joke: “Two elderly women are at a Catskill mountain resort, and one of ’em says, ‘Boy, the food at this place is really terrible.’ The other one says, ‘Yeah, I know; and such small portions.'” In those ancient days of my college experience there also seemed to be no end to repeating the same joke about Richard Nixon’s locution, “We can’t stand pat.” Of course he obviously meant that we need to keep moving forward. But Pat was his reliable spouse’s name. It was an unfortunate but funny unintended meaning that was further undermined by his dead-serious demeanor.

same message. Think of the old Woody Allen joke: “Two elderly women are at a Catskill mountain resort, and one of ’em says, ‘Boy, the food at this place is really terrible.’ The other one says, ‘Yeah, I know; and such small portions.'” In those ancient days of my college experience there also seemed to be no end to repeating the same joke about Richard Nixon’s locution, “We can’t stand pat.” Of course he obviously meant that we need to keep moving forward. But Pat was his reliable spouse’s name. It was an unfortunate but funny unintended meaning that was further undermined by his dead-serious demeanor.

We are all guilty of blindly producing unintended meanings. But in this age of distraction many of us don’t notice when we contradict ourselves in the same message. That’s why one is lucky to have someone who can be their formal or informal editor.

There is no shortage of examples.

A full-page ad in a recent issue of Psychology Today features an image of a counselor talking to college students under the shade of large tree. The counselor wearing an official-looking lanyard and gesturing to the others is obviously in charge. It’s the bottom headline that is out of sync. “Earn Your Counseling Degree Online,” it asserts. The college making this offer is apparently prepared to deliver to your computer nearly all of the skills and knowledge needed for a counseling degree. Is it possible to teach and master this kind of personal communication almost entirely on the internet? A promise of teaching full competence remotely needs more.

A full-page ad in a recent issue of Psychology Today features an image of a counselor talking to college students under the shade of large tree. The counselor wearing an official-looking lanyard and gesturing to the others is obviously in charge. It’s the bottom headline that is out of sync. “Earn Your Counseling Degree Online,” it asserts. The college making this offer is apparently prepared to deliver to your computer nearly all of the skills and knowledge needed for a counseling degree. Is it possible to teach and master this kind of personal communication almost entirely on the internet? A promise of teaching full competence remotely needs more.

- Lately I’ve been reading and writing a about Mark Twain, a towering presence in American literary history. Early in his career he expressed admirable outrage for the same kind of governmental grifting and malfeasance that we are seeing today. His

hostility to government leaders in the 1870s seemed prescient: an early warning for our own “Gilded Age.” And yet, as his biographers point out, his later years were often consumed in overspending on a lavish lifestyle, followed by dark moods when his investments floundered. I began to see my hero fading into the distance as he began duplicating the quest for easy wealth that he had criticized in his early writing.

hostility to government leaders in the 1870s seemed prescient: an early warning for our own “Gilded Age.” And yet, as his biographers point out, his later years were often consumed in overspending on a lavish lifestyle, followed by dark moods when his investments floundered. I began to see my hero fading into the distance as he began duplicating the quest for easy wealth that he had criticized in his early writing.

- There is an old advertisement for Alka-Seltzer Plus Cold Medicine featuring the testimony of a trucker, even though the medicine includes a warning to “not use heavy machinery” while using it.

- A few years ago I passed a car with a “Conquer Cancer” sticker on the back and a driver up front puffing on a cigarette.

- Denali National Park is pristine region of thousands of acres that is named after the Indian name of what is now been renamed Mt. McKinley, the highest Peak in North America. GMC clearly wants to invoke the same spirit of this natural wilderness with their popular Yukon Denali, a hulking SUV with, as one option, a gas V8 that gets 14 mpg in ordinary driving. To the extent that “the personal is political,” this seems like a non-sequitur on four wheels for any environmentally conscious driver.

Apparent contradictions can also yield pleasant surprises. I’m struck by the achingly beautiful music that was written by stoic men writing the last century, including Johannes Brahms, Edward Elgar and Sergei Rachmaninoff. Common motifs in many of their pieces are the very meaning of musical melancholy and wistfulness. Our modern view of masculine expression now admits to most of the same feelings that women express. Even so, and perhaps unfairly, I see in images of Brahms an unlikely figure to have produced examples like the 3rd Movement of the Third Symphony. The music of the Romantics is a reminder that a person’s appearance is an unreliable marker of what might be going on inside.

Apparent contradictions can also yield pleasant surprises. I’m struck by the achingly beautiful music that was written by stoic men writing the last century, including Johannes Brahms, Edward Elgar and Sergei Rachmaninoff. Common motifs in many of their pieces are the very meaning of musical melancholy and wistfulness. Our modern view of masculine expression now admits to most of the same feelings that women express. Even so, and perhaps unfairly, I see in images of Brahms an unlikely figure to have produced examples like the 3rd Movement of the Third Symphony. The music of the Romantics is a reminder that a person’s appearance is an unreliable marker of what might be going on inside.

- Facing politically divisive issues this June, President Donald Trump noted that “My supporters are more in love with me today, and I’m more in love with them, more than they even were at election time where we had a total landslide.” It was an odd kind of lexicon for a world leader to employ about him or herself. It is usually an insecure person might need to publicly affirm their popularity. That is usually left to others. Ironically, the compulsion to say it suggests the opposite. The spontaneous assertion of others’ love for oneself seems like reliable evidence of self-doubt.

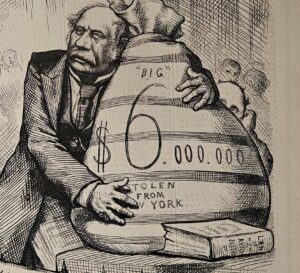

Anyone thinking that a corrupt and out-of-control federal government is a rare exception would do well to remember that Mark Twain’s well-named “Gilded Age: A Tale of Today” (1873) published in 1873 and featuring the same kind of grifting. Samuel Clemens as Mark Twain was a bitter critic of the superficial glitter that masked underlying social issues, highlighting the moral decay and the greed that characterized the era. To be sure, Twain later had his own investment and money-making schemes, mostly centered on printing and publishing. But along with the book’s co-author, Charles Dudley Warner, he viewed this period as a time of chaotic social upheaval, marked by rampant corruption, business speculation, materialism, and a vast contrast between the wealthy and the impoverished masses. As a recent PBS documentary about this period noted,

Anyone thinking that a corrupt and out-of-control federal government is a rare exception would do well to remember that Mark Twain’s well-named “Gilded Age: A Tale of Today” (1873) published in 1873 and featuring the same kind of grifting. Samuel Clemens as Mark Twain was a bitter critic of the superficial glitter that masked underlying social issues, highlighting the moral decay and the greed that characterized the era. To be sure, Twain later had his own investment and money-making schemes, mostly centered on printing and publishing. But along with the book’s co-author, Charles Dudley Warner, he viewed this period as a time of chaotic social upheaval, marked by rampant corruption, business speculation, materialism, and a vast contrast between the wealthy and the impoverished masses. As a recent PBS documentary about this period noted,