[Though many Americans have turned coffee into a bizarre kind of fountain drink, coffee retains its hold on us. This piece from 2015 is a reminder of its efficiency at helping reluctant neurons fire.]

New Yorker Cartoonist Tom Cheney obviously loved coffee. A lot of his cartoons featured the stuff front and center. My favorite was entitled the “Writer’s Food Pyramid,” with a food-group triangle of “essentials” for scribes that would give most dietitians severe heartburn. His pyramid was a play on those dietary charts that usually adorned classroom walls in the 80s. At the wide base of Cheney’s list were “The Caffeines” of cola, coffee and tea. They anchored the rest of a pyramid of necessities which included “The Nicotines,” “The Alcohols” and “Pizza” at the very top. Tough nicotine from tobacco has lost of most of its charms, the rest still make the perfect fuel cell for a cultural worker.

Many of us owe the completion of at least a few big projects to the caffeine that the brain needs more than the stomach.

Cheney obviously knew a lot about writers with their old typewriters, which movie mogul Jack Warner once hilariously dismissed as “Schmucks with Underwoods.” But there’s actually some method in all of this madness. Communication—at least the process of generating ideas—is clearly helped the spur of this addictive substance. We have more than a few studies to suggest that writers and others who create things can indeed benefit from the stimulant. Notwithstanding a recent New Yorker article suggesting just the opposite, caffeine is likely to enhance a person’s creative powers if it is used in moderation. I’m sure I’m not alone in owing the completion of at least a few books to the sludge that now makes my stomach rebel. As for decaf: it seems like the food equivalent of a non-sequitur.

It turns out the stimulant has a complex effect on human chemistry. As James Hamblin explains in a June, 2013 Atlantic article, caffeine is weaker than a lot of stimulants such as Adderall, which can actually paralyze a person into focusing for too long on just thing. It’s moderate amounts that do the most good. Even the New Yorker’s Maria Konnikova conceded the point. She noted that it “boosts energy and decreases fatigue; enhances physical, cognitive, and motor performance; and aids short-term memory, problem solving, decision making, and concentration … Caffeine prevents our focus from becoming too diffuse; it instead hones our attention in a hyper-vigilant fashion.”

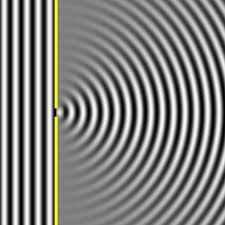

To put it simply, the synapses happen more easily when that triple latte finally kicks in. A morning cup dutifully carried to work even ranks over keeping a phone in one hand.

But there is an exception. A person facing a live audience in a more or less formal situation probably should avoid what amounts to a double dose of stimulation, given the natural increase of adrenaline that comes when we face a public audience. For most of us a modest adrenaline rush is actually functional in helping us gain oral fluency. It works to our benefit because it makes us more alert and maybe just a little smarter. But combining what is functionally two stimulants can be counter-productive. They can make a presenter wired tighter than the high “C” of a piano keyboard. We all know the effects. Instead of the eloquence of a heightened conversation, we get a jumble of ideas that are delivered fast and with too little explanation. In addition, tightened vocal folds mean that the pitch of our voice will usually rise as well, making even a baritone sound like a Disney character.

All of us are different. But to play the odds to your advantage, it is probably better to reserve the use of caffeine for acts of creation more than performance.

![]()