Paterson is remarkable for its director’s ambition to build a story around a character’s interiority.

There is something surprising and satisfying about Jim Jarmusch’s 2016 film Paterson, which chronicles the creative life of an everyman poet. The film follows its dominant character through a series of routine work days. He’s a bus driver, using the freedom granted by the predictability of his route to work out lines of poetry that are committed to paper at the end of the day.

Each morning he leaves his small bungalow and his artist wife for the short walk to the bus barn. Even on his feet he’s a natural observer; and Jarmusch gets out of the way to let us see the modest city that reveals itself every day. Once underway, it’s mostly the driver’s ears that take over, catching the conversations of the children and seniors who depend on his NJ Transit bus. He also absorbs the lives of locals in a neighborhood bar he visits after dinner. It’s part of his routine of taking the couple’s English bulldog for a walk. (Marvin was played by Nellie, who won the Palm Dog Award at Cannes).

If this all sounds like watching paint dry, you’d be surprised.

The film’s title has at least three meanings. The young driver’s name is Paterson. The town he lives and works in is also Paterson, in Northern New Jersey. And the name happens to be the title of William Carlos Williams’ most consequential book of poetry, which sits on Paterson’s desk.

Actor Adam Driver is skillful enough to let us see Paterson’s mind absorb his world. In this story there will be no crashes, no hold ups, or any break in the loving bond between himself and Laura. Instead, Jarmusch focuses on the linear thinking of Driver’s character, a man intent on working out his thoughts. Paterson doesn’t even carry a cell phone, which he perceptively sees as a distraction and “a leash.”

Periodically Jarmusch lets us see the results of Paterson’s verbal invention in his own scrawl. It unobtrusively slips under the film’s images in a corner of the screen. The lines contributed by writer Ron Padgett are very much in the Williams tradition: an economical free-verse style.

Motion pictures generally work from the outside in, using action rather than thought as motivating elements.

Here’s the interesting thing. Paterson is remarkable for its willingness to build the film around a character’s interiority. Films often show us a great deal, but usually starve our interest in understanding a figure’s state of mind. Motion pictures generally work from the outside in, using actions rather than thought as motivating elements. Actors may want internal motivations to bring their characters to life. But directors naturally want something interesting to show.

And there’s the rub. Poetry is frequently about passing impressions, layers of revelatory consciousness that are eventually made audible. As a form, it’s not necessarily fragile, but it is often subtle. A director has to be inventive and confident to put stories on the screen that build out from the inner life of a poet.

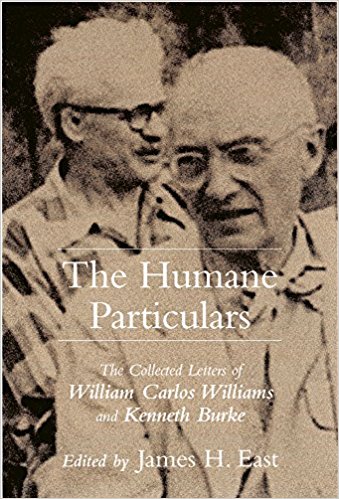

Interestingly, Williams was a friend of Kenneth Burke, perhaps the most influential of all American rhetorical scholars. When he visited Burke’s farm in Andover New Jersey the two men—Williams, a physician and poet of the ordinary, and Burke, the grand theorist of all things symbolic—would sometimes goad each other. Williams might gently mock Burke about his “damned theorizing.” But both thrived in the same realm of words and thought. Burke was driven by the desire to create a grand theory of everything, as revealed in our symbol-using. Williams often sought to record what his senses were telling him about about his busy life in the Garden State. That a film would seek to enter this world of verbal action is a reminder of the kind of transformative story an observant filmmaker can tell.