The toughest challenges any nation faces are usually systemic. And most are out of reach of filmmakers or photographers.

The familiar saying that “a picture is worth a thousand words” is one of those aphorisms that is so self-satisfying that we know we are never going to be challenged when we say it. But its not only wrong, its inverted. In fact, a picture is sometimes worth very little, and—at times—a distraction that costs us dearly.

Nearly a century ago the philosopher Susanne Langer made the obvious but profound observation that images are presentational; they easily reflect a piece of the material world back to us. Presentational media allow immediate and nearly universal access to all that can be seen, aided by the fact that–unlike texts–we don’t have to learn how to “read” images. To be sure, we can become visually more astute. But some visual content like the human face is instantly ‘readable.’ Even infants have this capability.

To be sure we need images: perhaps to inspire us, or maybe to simply figure out which slot of an electrical outlet is the “hot” side. But as Langer pointed out, language goes where visual artists can’t. It’s often the only suitable vehicle for expressing ideas, beliefs and values. And though we may doubt it, all of these are generative: they are among the first causes of why we think as we do: what we cherish, and what first principles we value.

Imagine you are putting together the 6:00 o’clock edition of a local television news show. In the competitive world of commercial television the last story you want to cover is one that needs an extensive verbal explanation. Your survival depends on showing rather than telling. In most cases news-gatherers are going to prefer blood on the pavement to sociological explanations that account for an increase in a city’s crime rate. Similarly, the same preference for the visual will devalue a story with an advocate explaining, say, the advantages of a single-payer medical system. The subject would make most video producers blanch. Other than a “talking head,” there’s nothing to show other than old “B” roll footage of patents sitting in medical offices, or perhaps a doctor taking someone’s pulse. A problem with television news is that its disparate and continuous search for interesting pictures distorts our attention. First causes are hard to show. So we may see patients describing the hardship of paying for out-of-pocket medicines. Their fears and anxieties work well in presentational media. But we are less likely to see a video analysis of American healthcare, or the parity-violating idea of rationing it. The uneven denial of some coverage—our de-facto system for all but the very rich—needs a rhetorically adept explanation. And if an expert goes before a the camera, they will be asked to keep their explanations very short. Think seconds rather than minutes.

Systems of belief can hide from the camera. Hence we may never give them the scrutiny they deserve.

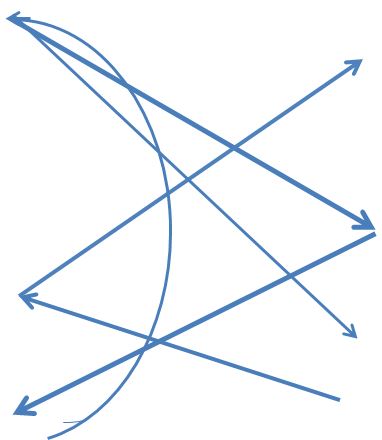

Here’s the problem, and its a huge one: the toughest challenges any nation or community face are usually systemic. That is, deeply embedded problems arise from old and rarely examined attitudes, ideologies, procedural traditions or group fantasies that must be described rather than shown. They are beyond the reach of even a talented video producer. In our ocular-centric world we can indeed see the effects of our worst problems: for example, urban poverty, poor schools, serious crime, industrial pollution, and so on. What can’t be reached with a camera are the fixed ideas–our ideological roots–that perpetuate them.

Consider a final brief example. Industrial pollution sometimes happens because industry lobbyists sometimes provide the legislative language for lax government regulations. But we don’t see that. There’s really nothing to show. The real action is in the almost invisible transfer of regulatory power from elected officials who are too close to the regulated, a significant slight-of-hand that does not make very interesting pictures. A competent political journalist or academician can explain these suspicious legislative alliances. But a reporter doing this kind of story will have to beg for screen time.

The effects of news driven by the need for interesting pictures is that we are often only moved by portrayals of feelings. That’s fine, but it often comes because we have a enfeebled tolerance for the discursive detail of print on the page or screen. Images are emotionally involving. But ideas require literacy and our willingness to use its tools.

![]()