I wonder what it means to carry the awareness that we have bullseyes painted on our backs.

There’s something inherently disconcerting about being a “target.” The lethality implied in the early use of the term is still with us, more than it should be, but its also obvious that its meaning has clearly broadened. Even so, the 17th Century origins of the term are grammatically consistent with how we still use it today, namely: to be the object of another’s attempt to have us yield. In the noun form, a “target” is a person. As a verb, to be “targeted” means that we are the quarry of someone else. A word rarely heard by our ancestors is now firmly in the canon of common usage.

In different language, the idea was even a rule of thumb for Aristotle, who instructed citizens of Macedonia on how to assess audiences, adjusting verbal appeals to match their characteristics.

What is so striking about the modern use of the word in marketing and every kind of communication is that it has become ubiquitous. A pitch for almost any ideology, service or product is strategically designed to convince anyone identified as falling within the target audience. This is still standard lingo of Marketing 101. My guess is that even children as young as eight or nine understand this form of exchange in what is too often a one-way transaction. Sellers often seem to reap benefits from their “core demographic” that exceed what comes to the buyer. This “margin” is a bedrock of American consumer culture.

I wonder what it means psychologically to carry the awareness that we have bullseyes painted on our backs. Our daily consciousness can’t help but remind us that we are being tracked for what we represent rather than who we are. We cannot live in this culture without the knowledge that others are interested in us less as free agents and more as bodies ready to comply with particular appeals. Add in just enough delusion, and someone within a target audience may be flattered by the apparent attention. But those who are more aware know better. Even so, the wary will still be among the consumers who collectively lost $3.3 billion in 2020 from online scams and other offers of things or services that were never delivered.

We now occupy a world where software makers target us with appeals to buy computer protection to ward off many others who target us for personal gain. On the internet, easy anonymity and clever algorithms mean that the odds can favor the grifters.

The side calculation of estimating our trust in others

To be sure, targeting is not always easy. It must happen amid an overload of channels and platforms, reducing the effectiveness of any one appeal. Selling today means aiming for prey concealed in a forest of competing distractions. Being noticed is one problem; being persuasive is another.

But the game persists. The uber-strategy of targeting has altered the ways we relate to others. The awareness of being in the crosshairs and about to receive another’s self-serving messages makes us wary. We are often unsure who we can trust. Interestingly, the idea of a person with “good character” who merits our confidence was Aristotle’s gold standard for effective persuasion. In his words, who we are often speaks louder than what we say. Now, we must now constantly do side calculations to determine who among our many contacts will not violate our the faith we have placed in them. Every calculation pushes us further into defensiveness and suspicion: realms that, among other things, are fertile ground for conspiracy theorists.

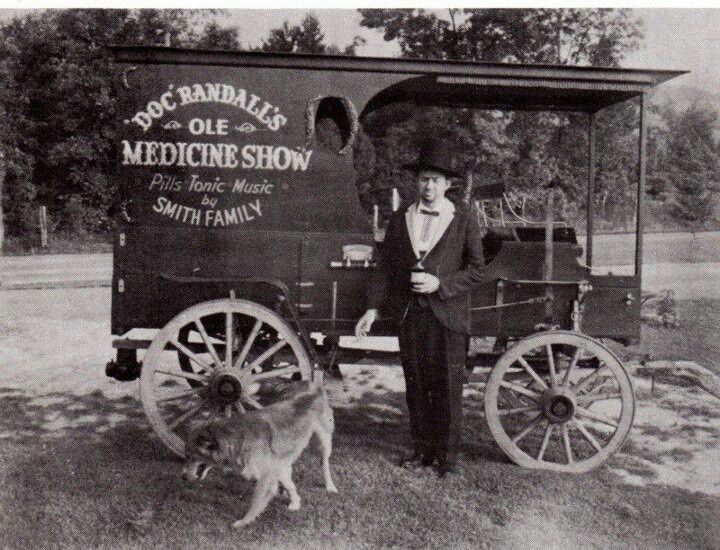

So, rhetorically, we now sit in a very different place. The strategy of the “double game” played for laughs in old classic films like The Music Man (1962) or The Sting (1973) has now taken on the attribute of a common norm applied to messages that come to us from beyond the small bubble of family and friends. What was once a plot device has become a dominant and darker transactional pattern.

![]()