The truth is that we don’t really know why despair appears to be spreading across Middle America. But it clearly is, with troubling consequences for our society as a whole.

–Paul Krugman

A number of indicators have come together in the last year to suggest that the optimism that has flowed from the American faith in a better future is drying up. Poll data from Pew and others confirm that about half of Americans believe the country is on the wrong track. Moreover, wage growth especially in the middle class has stalled. There’s even a vocal minority in the Congress that believes federalism is so broken that the best remedy is simply to shut the government down, at least until budget reforms are made. Add in the current presidential campaign with its apocalyptic rhetoric, and the cloud we are under looks ominous indeed.

To be sure, some of this rhetoric of despair is a common pattern for political challengers, especially if regaining the prize of the White House seems far from certain. Even so, the mood of gloom that permeates most of the corners of our public life seems broad and deep, typified by descriptions of current presidential actions in draconian language usually reserved for America’s Twentieth Century enemies: German Nazism and Soviet-style Communism.

Of special interest is new evidence from various sources indicating earlier-than-expected mortality for white middle-aged Americans in the center and southern tier of the United States. Citizens in the nation’s interior who are struggling to remain in the middle class are dying prematurely. Economists, Angus Deaton and Anne Case recently reported that the death rates for whites 45 to 54 who never attended college increased by 134 deaths per 100,000 people between 1999 and 2014. This rise is in contrast to rates in other ethnic categories that are slowly falling.

The immediate causes are suicide and the abuse of drugs and alcohol. The underlying causes are more intriguing and obscure.

The data has interested economists like the New York Times’ Paul Krugman because there seems to be a possible correlation with what he describes as the “harrowing out” of the middle class. Wages in all but the top sectors of the economy are flat. Corporate consolidations continue to squeeze out “excess” workers. And good paying industrial jobs have mostly gone away, replaced in some places by the kind of piecework and part-time employment offered by Uber, Wal-Mart, universities, and other “new economy” employers who want workers, but without providing the traditional benefits that come with full-time employment.

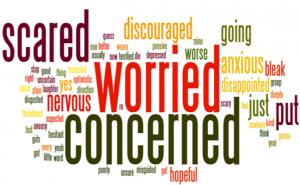

Finding true first causes for these rising mortality rates is a tricky business. But understanding the consequences in terms of how people register their opinions is far easier. Consider the word cloud at the top of this piece from the Gallup Organization. It represents common terms heard when Americans were asked several years ago to describe their government. To no one’s surprise pessimism reigns.

Similarly, blogger Sean Carroll’s own cloud of words commonly in the GOP represent their own unease about where the country is headed:

This generalized angst is now regularly on view at meetings such as the annual CPAC conference of movement conservatives. Ben Carson speaking in 2013 sounded as if the President of the United States was actually out to sabotage the durable roots of the republic.

Let’s say somebody were [in the White House] and they wanted to destroy this nation. I would create division among the people, encourage a culture of ridicule for basic morality and the principles that made and sustained the country, undermine the financial stability of the nation, and weaken and destroy the military. It appears coincidentally that those are the very things that are happening right now.

Again, we would expect the party out of power to emphasize concerns and problems. But political rhetoric usually comes with some built-in optimism, as in Ronald Reagan’s constant reassurance that “America’s best days lie ahead.”

Beyond economic and political motivations for this reign of despair, I would add a secondary cause that has unleashed its own demons across the culture. Although I’ve straightened the arrows of causation somewhat for the sake of space, its clear that one condition that has changed in recent years is that under-occupied members of society are less able to keep the dispiriting dregs of human conduct at bay: a significant effect of media that contribute to a weakening of our faith in an ordered world.

Here’s what I mean. The presence of ubiquitous connectivity and growing hours of screen time means that we cannot easily do the gatekeeping that was more easily achieved when roots in the community were deeper and accessibility to the outside world was less constant. Think of 1980 before digital media, trolls and journalistic bottom-feeding. While media were once heralded for expanding our horizons, we now function in white-out conditions of over communication that obliterate them. Given all the bizarre forms of clickbait that pull us in, we now “live”–if that’s the word–everywhere and nowhere. To speak in older 20th Century terms, we no longer let ourselves stay very long in the secure “real time-space frame” of family, work and friends.

Endless evocations of the absurd have their effects. We spend more time with “virtual” friends, virtual news, and the attenuated grievances of those on the margins who are given their provocative moments to act out in front of a camera. All of this has weakened our anchors in the more nurturing world of direct interaction. A person who has planted him or herself in front of a computer for the requisite six hours knows all too well the feeling of creeping isolation that comes with the supposed benefits of hyper-connectivity.

comments: woodward@tcnj.edu