Internet giants seem to be racing to the bottom by turning their news sites into picture books with bright colors and sparse content.

Tech is turning out more drek. Why is almost every site trying to convert their news into clickbait pictures? We don’t need to see B-roll footage of the misery in Gaza for a story about what the next steps to secure peace might be. The real news lies in the thinking of figures in Gaza, the White House and Tel Aviv. We also need clear numbers rather than images to account for the ruinous health care costs facing many Americans.

For what it is worth, this insight came to me after a necessary upgrade to Windows-11. After purchasing a new computer to be able to manage the decidedly underwhelming software, Microsoft thrust it’s MSM Webpage at me as an added bonus. It was enough to trigger my frustration.

Their page of ads and news “stories” caught my eye quite literally. The layout of the version I saw was a stash of videos dealing with everything from the weather to news about barely qualified people seeking White House jobs. The real meat of some of these stories could be more efficiently presented in straightforward reporting and more than 500 words of text.

One medium is never fully convertible into another medium.

We all love visual stories. But the hard truth is that a person’s world becomes highly circumscribed if their access to big and important ideas is hobbled with the need for interesting pictures. I noticed my frustration because my new computer came with glitches that needed to be fixed by adjustments to specific settings, none of which were well explained by a person on YouTube who assumed his job was to show me something. I was looking for lists and sequences, which had to be awkwardly communicated off camera by a tech who was trying to be helpful.

My mistake was turning to a visual medium. I finally got help from a print-oriented forum where the emphasis was on explanation and amplification, not interesting images.

As this site has noted before, many worthy ideas do not have an easy visual form. Policies, values, administrative decisions, directions on fixing a computer problem and similar kinds of topics need discursive amplification, not a talking head proceeding at the glacial pace of 200 words a minute. Ditto for help in speeding up my slow computer. YouTube can be helpful in showing how to fix things; but not so much if there is a lot of telling to do as well. It has unfortunately become the default medium for explaining something, even when the explainer has no flair for visual communication. It is used because it is there. If you find yourself frantically taking notes from a segment, you can understand the paradox of having to translate from a medium of images to a medium of ideas. As we know, at least intuitively, one medium is never fully convertible into another medium.

Recent news stories report another decline in the reading ability of the nation’s grade-schoolers occurring along with handwringing from professors at Harvard complaining that their students won’t read. If we wonder what the cost of turning our kids into smartphone addicts is, we may not need to look any further. The small screens of those phones and their equivalents are full of junk images and too little supporting text.

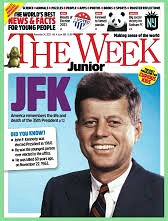

It does not have to be this way. A glance at The Week Junior, the popular weekly news magazine for kids, shows how non visual topics can be covered in effective ways. Even subjects like freedom of speech and the characteristics of good poetry can be explained in interesting and age-appropriate levels. The Week Junior is a model of how our children should spend more of their time.

It does not have to be this way. A glance at The Week Junior, the popular weekly news magazine for kids, shows how non visual topics can be covered in effective ways. Even subjects like freedom of speech and the characteristics of good poetry can be explained in interesting and age-appropriate levels. The Week Junior is a model of how our children should spend more of their time.

Obviously, visual clickbait functions as a hook to pull a consumer in. But I worry that we are aiming at the low. Young “readers” may need primary colors and cartoon images at the gateway of literacy. But older readers should be self-starters. If we allow the acquisition of knowledge and new information to proceed at the pace of a poky PowerPoint show, we can only admire our predecessors who understood that advanced insights require the incisive comprehension of a master reader.