For a devoted cadre of individuals, a home is the defining feature of a satisfying life.

“People centered” versus “place centered” offers a categorical and crude binary. We are never as simple as we might imagine. Even so, I am surprised at how often a person clearly becomes energized by where they reside or where they have been. For some, a physical place defines a person’s functional world more clearly than the interpersonal contacts they have. Houses are especially expected to function as refuges where the familiar becomes the comfortable: settings where markers of identity take shape and make a “home.” Journalists are fond of noting that someone’s residence has become an extension of their personality. We often hear that a room is a “reflection of an individual’s personality.” The photographs that prove it may not even include the occupant. The living spaces are said to ‘speak’ for themselves.

The master director James Ivory organized his most successful narratives around places: for example, the stately homes in his dramatizations of E. M. Forster’s Howard’s End (1992) and A Room with a View (1985). Ivory’s opening shot for Howard’s End wordlessly explores what a place means to one character’s identity. She strolls around the outside of her country home as dusk, the warm light inside revealing her animated family playing cards. The view from the outside is a visualization of her ideal. See loves the idea of the house. Only later when we meet the family do we see the tensions.

Even as a teen, Ivory recalls how he loved to visit the Thorne Miniature Rooms at the Art Institute of Chicago. Every detail is perfect in these three-dimensional miniatures of drawing rooms and bedrooms. They are a good representation of the “domestic perfection” that he and producer Ismail Merchant loved to put on the screen.

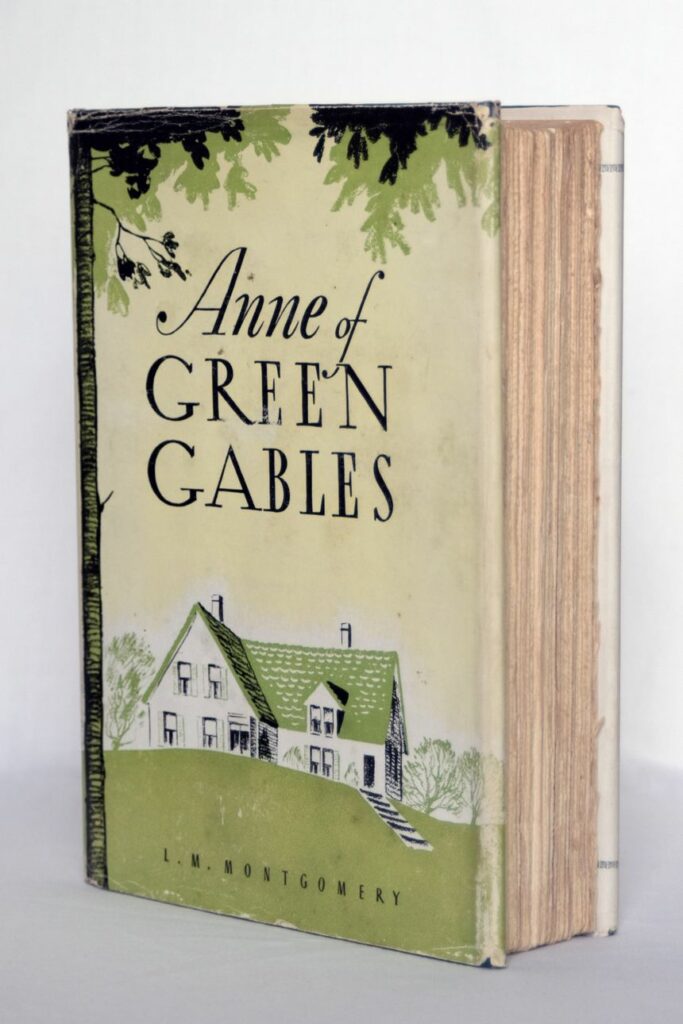

There is no shortage of stories where a home is the key character. Theater of all forms needs a scenic dimension, even if it is as prosaic as the contemporary houses in Steven Spielberg’s domestic dramas. Anne’s Shirley’s Green Gables modest farmstead on Prince Edward Island and Mr. Blanding’s problematic “dream house” being constructed in Connecticut (1948) are essential to their stories. More baroque is Rebecca’s shadowy Manderley (1940), or the vast spaces of Downton Abbey (Highclere Castle), where the aging roof has as many holes as some of the plot lines.

Homes can also be a malevolent character in a story: a narrative decision against type that violates usual expectations. Films like Poltergeist (1982), Netflix’ current The Watcher (2022) or The Amityville Horror (2005), all play with the familiar theatrical trope of home as a safe refuge.

We can approach the specialness of place from another angle as well. It is revealing to see what people choose to hang on their walls. Set aside a few obligatory photos of the family for a moment. Is the art mostly portraits? Landscapes or seascapes? Are the pictures in place to act as reminders of past or fantasized experience? And might it also be true that, for introverts, a “perfect” landscape like a Thomas Cole painting gets a prime spot because no person intrudes? I have a hunch, but nothing more than that. I suspect that it may be easier for many of us to idealize a place more than an individual.

For the modern art establishment, landscapes are especially passé. We expect interpreters of our world to give us a sense of lived experience: whether hopeful or disturbing. But the shopkeeper at any tourist spot will tell you that the popular art and reproductions that sell are usually conventional versions of the local scenery: perhaps the hillside villages of Cinque Terra above the Mediterranean, or the colorful mud pots of Yellowstone, or perhaps an over-the-top Kinkaid cabin in the woods.

The subject of shelter is a natural human concern. As the blight of far too many homeless remind us, humans need the protections of a closed and familiar space. Only 64 percent of Americans own a home. But as any viewer of the large number of home shows on television will know, the culture has passed the “need” level for shelter decades ago. In our media homes are now presented as stage sets: actual or aspirational. Many are especially prone to building trophy kitchens, even if they almost never cook and would be quick to dismiss Julia Child’s unglamorous workaday space preserved at the Smithsonian Institution. Indeed, a visitor transported to the present from America of the 1950s would be tempting to conclude that we have their turned homes into temples of affluence. Its easy to find fetishized “residences” in nearby suburbs where perhaps only the gardeners have ever walked around the properties. Celebrating their acquisition in print and pixels is its own reward.

But I’ve hedged the question. What predilections motivate many of us to warm to places more than persons?

![]()