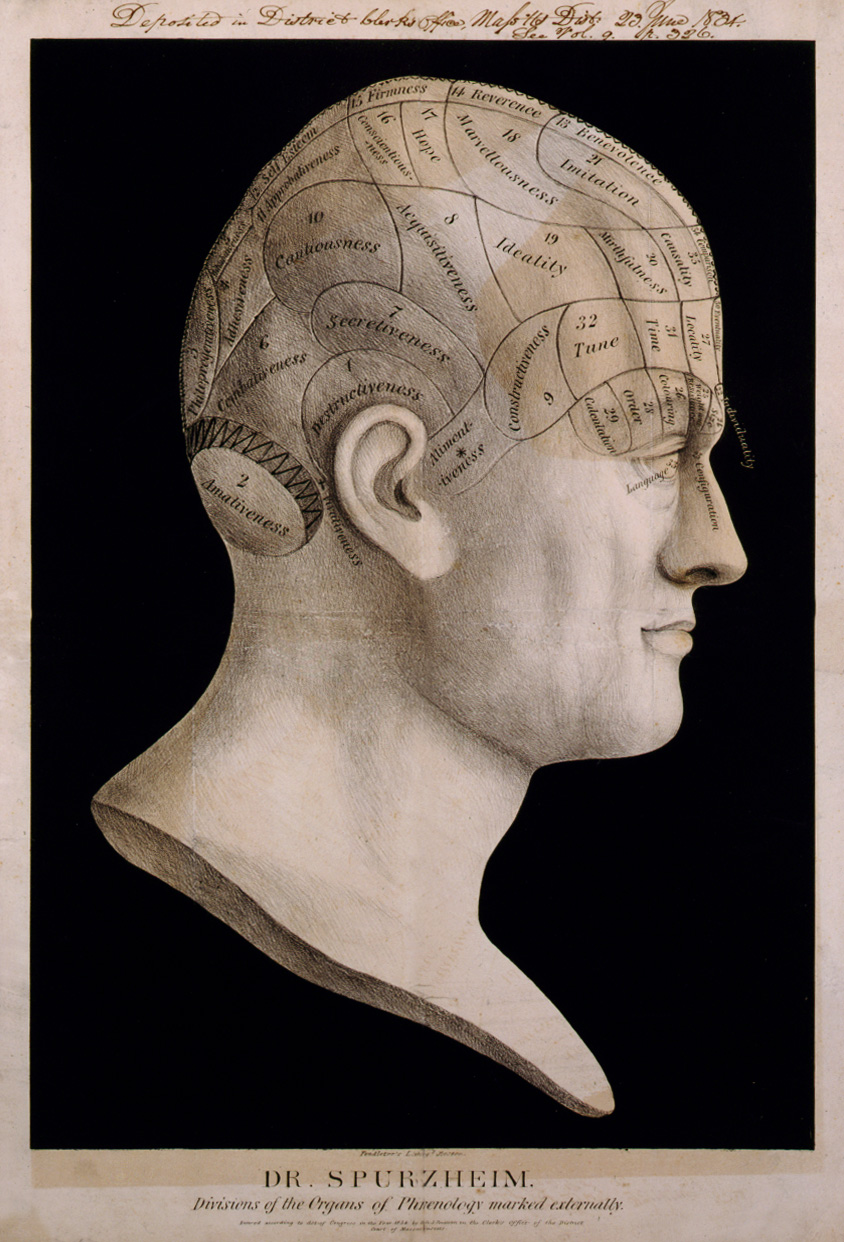

We are the species that ponders, muses, worries, fears, wonders, hopes and ruminates. It follows that we are also wired to make estimates of another’s state of mind based on almost anything they to say.

We know humans have rich inner lives, and that values and concerns are indirectly signaled to others in what we say. There is a sub-textual ‘meta-language’ that is embedded in the thoughts we express. Expression naturally reveals residues of the mind in motion. Not surprisingly, our skill at “reading” each other turns out to be one of the crucial markers of a person’s social intelligence. State-of-mind inferences are what make discourse possible. Our estimates usually mean that we can adjust to meet an interlocutor half way.

Our skill at ‘reading’ others is a crucial attribute, separating humans from other species, even smart robots. We might expect that Alexa, Siri and their counterparts will be able to answer truth-based questions. But we are usually going to come up with blanks if we look for signs of some sort of inner life.

This is why interiority is such an interesting idea.

A robot can be programmed with words that mimic feelings; it can also be programmed to have a kind of synthetic past. But ask Alexa what kinds of topics are most difficult to discuss, and we are probably going to get some version of it’s programmer’s interiority. Shift toward the stuff of everyday human life–feelings, experiences, a sense of self–and machine intelligence begins to founder as a pretender to the human mind.

We routinely act on the belief that we are mostly transparent to each other.

All of this is a useful reminder of how much we depend upon what is sometimes called “theory of mind” to infer mental states in others. The trigger is almost always our statements and their accompanying physical expressions: even simple cues like frowns or smiles. These are enough to turn the mysteries of another into estimates of apparent needs and aspirations. For example, if a friend tells us that someone we both know seems “on edge,” it’s entirely possible that the rhetorical signs of that state were inferred from statements ostensibly about something else. We assume there is a meta-language even in the most prosaic forms of rhetoric. What we sense is easily passed on in similar statements like “She seems lonely,” “I think he lacks self-confidence” or “She says she’s fine, but she doesn’t seem fine.” In short, we use the evidence of another person’s words to fill in a larger picture of their preferences and predilections. And while this is not psychoanalysis, it is a survival skill for a species that lives in communities.

All of this means that we act on the belief that we are partly transparent to each other. We count on our inferences to build out the bonds we seek with others. To be sure, most adults maintain a screen of privacy that can seem impenetrable and not easily inferred. In addition, our inferences can be wrong. Friends can surprise us with unanticipated feelings or reactions we didn’t expect. Even so, the daily business of making estimates of what others are thinking demonstrates a kind under-appreciated mindfulness.

And yet. . .

A Trump Caveat in Four Questions

Most of us are somewhat opaque. We keep a great deal behind a scrim that decreases our revealed vulnerabilities. We know more of our successes than we might say. We sense our fears, but suppress the impulse to speak about them. We rein in the rampant narcissism that once flourished in childhood.

But what happens when a person lives their life in a cognitive glass house? An absence of self-monitoring can mean that elemental needs, fears and resentments are likely to be on display with technicolor vividness. No inference-making by another is required; the person is psychologically naked.

This rarer form of what might be called “interiority at the surface,” is evident in the psychic transparency of Donald Trump. Even if we set aside his politics, it’s apparent to most Americans that obvious needs for status and affirmation float to the top of everything he says, like bubbles rising from the bottom of a pool. He’s the rare leader who has grown to adulthood seemingly unaware of the near-total display of his core motivations. To be sure, the surface bluster is convincing to some. Yet there is a far more common counter-narrative of something amiss just underneath, a chronic vulnerability made worse because he lacks awareness and self control. Without doubt, many chronic self-promoters can be blind to their obviousness. Even so, the problem of Trump’s externalized interiority poses stark questions for him and citizens alike:

- Does he not notice that his words so obviously betray his needs and fears?

- Has he never found reasons to admire the stoicism and mental discipline of John Kennedy, Martin Luther King or John McCain?

- Is there ever an impulse to lash out that’s worth suppressing?

- And should it always fall to ‘minders’ and citizens to worry about a leader who presents himself to the world as hopelessly insecure?

In a more usual case we will have to infer aspects of a person’s inner life, and that living with a certain degree of grace means keeping a filter in place between private resentments and public words.