In our narratives about how our world works we lean heavily on the idea of cause-and-effect predictability. But a causation slot that must be filled in makes the world seem more knowable than it really is.

In his book How The Mind Works (1997) psychologist Stephen Pinker notes that the very idea of science assumes that there are direct causes for any material effect. Ask an experimental psychologist about the nature of a particular behavior, and the conversation will eventually drift toward its possible social or familial roots. Look at research on urban gangs, and the talk will soon include the contributing forces of peer and environmental factors. The social and hard sciences are generally in the business of seeking first causes. They need this conceit in order to work. To be sure, we are often better off because of their efforts, but not always.

For most of us this science template has probably infused itself in the ways we make sense of the everyday world. Looking for causal chains seems like the very definition of mental rigor.

From this perspective cataloguing effects is not enough. For example, uniform crime reports are interesting, but only get us so far. Our accounts for how the world works is anchored in our faith that things can only get better when causes are revealed and controlled. After all, events without apparent causes are disorienting. A tree that falls and kills a passerby tests out willingness to accept seemingly random events with lasting consequences. We want to know why, and how to control conditions that can prevent such deadly events.

From this perspective cataloguing effects is not enough. For example, uniform crime reports are interesting, but only get us so far. Our accounts for how the world works is anchored in our faith that things can only get better when causes are revealed and controlled. After all, events without apparent causes are disorienting. A tree that falls and kills a passerby tests out willingness to accept seemingly random events with lasting consequences. We want to know why, and how to control conditions that can prevent such deadly events.

Even with this natural impulse, we overuse the template. A causation slot that must be filled in makes the world seem more knowable than it actually is. We cherish lexicons of determinism. For example, we easily classify people into personality types, where the labels (“neurotic”, “needy,” “depressed,” “obsessive,” to name a few) become concrete explanations for behaviors tied to personality traits. But why Aunt Millie has a personality disorder is still anyone’s guess. Similarly, when a plane falls out of the sky we resort to the same template for making sense of what has happened. When we ask “what went wrong?” we expect a precipitating cause to be named. Only later do accident investigations usually reveal multiple problems that combined to create a disaster.

In our rushed and over-communicated age we rely heavily on the simplistic explanation.

Consider a different kind of example. Imagine if you are a neuroscientist. How long can you retain your professional credibility if you take the risk of acknowledging that the mind is partly “unknowable?” Neuroscientist’s study the brain and generally shun discussion of the “mind,” the useful label for what the brain has given its owner by way of a wealth of experiences and perceptions. What I see in my ‘mind’s eye’ is likely not what others see. But how do we find the causes for those mindful thoughts? A brain scan won’t cut it. Consciousness can’t be reduced to predictable neural pathways. And so the idea of mind muddies the scientific impulse for the measurement of particular effects. Thus the brain sciences generally remain silent on this rich idea, preferring to study the organ of thought more than thought itself.

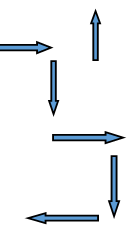

This kind of problem is why the search for first causes tends to force us toward the absurdly technical or the overly simplistic. On the simplistic side, compressed ideas about why things happen indeed yield answers: usually good enough to see us to the end of the day, but not very reliable as bases for creating lasting understandings. The shorthand vocabulary of causes that we inevitably use give us dubious deterministic links that we nonetheless cling to. And so Muslims cause terrorism, African-American males are dangerous to be around, and politicians are corruptible. Each labeled category is pushed next to an arrow that points to a list of supposed causes, producing “answers” that in their narrowness are hardly worth knowing.

Sometimes the best response in reply to an unfolding set of events is uncertainly. Even with the need for simplicity in our busy lives, we have to save room to let in the messiness that is part of the human condition. Instead of imagining arrows, we need to think of webs. A web is a better representation of lines influence that are complex and pass through rooms of intermediate and unknown causes. If we want to be a little smarter all that is required is the resolve to give up the short-term thrills of unearned certainty.

![]()