Character measured by known virtues like honesty and doing good works was a huge concern for classical thinkers. Why do we now find the carnival barkers in our midst more worthy of our time?

It seems like a paradox that, amidst sufficient information to draw conclusions about the quality of a public person’s character, vast segments of the American public are unable or unwilling to notice disqualifying flaws. To be sure, humans can be taken in by scoundrels in any era. From Professor Harold Hill to Bernard Madoff, the charlatan “on the make” is a distinct American type. Among many others, historian Daniel Boorstin was especially vivid in chronicling American hustlers with a gift for self-promotion but a tenuous grasp on the Truth. Even when serious flaws of character become known, many of us have an incapacity to see them. Indifference also seems to be the norm, even when we will pay a deep price for believing fraudulent claims. It was so for citizens of New York’s 3d congressional district, who trusted George Santos . Years ago folks in Wisconsin fell for the the same kind of destructive character in the person of Senator Joe McCarthy. And it many be worse now; Congress has an entire “chaos caucus” of loquacious but slow thinkers.

What thoughts are reflected in those enthusiastic faces we see planted behind felonious candidates at their political rallies? Why do persons with the cultural tools to sense the mendacity of others still fail to act react appropriately? Clearly many of the nation’s collective woes are due to widespread indifference to signs indicating that a person should not be trusted to lead.

![]()

There is a useful thought-experiment here to puzzle out why traditional virtues of character have withered in the public sphere.

Our public reasoning has become inverted. Incredibly, every new formal accusation brought against former President Trump has produced a new levels of support, as if we were talking about parking tickets rather than civil convictions for a sexual assault and tax fraud. The ostensible ‘bad news’ that in more sober times would have disqualified a leader now seems to boomerang. It is not just the shabby spews of ad hominem attacks from Trump that have given our public life an Alice in Wonderland aspect. We can find similar lapses of judgment in other leaders in business and the arts.

The word itself now seems like an antique, but virtue actually has a long history in the classical world representing the general idea of a good person.

Giants in western philosophy such as Aristotle (b. 384 B.C.) and Cicero (b. 106 B.C.) have explored the subjects of the virtuous and the good. They are mentioned here because—among their many interests—both were rhetoricians interested in how audiences react in the presence of those who would influence them. For Aristotle, a good person had high ethos, meaning a person was known for virtues that included prudence, sense of justice, temperance, and courage. Their known strengths preceded them. Persons known to be burdened with the baggage of low credibility (meaning an indifference to the Truth, or ways to test it) were seen as lacking high ethos. Having the virtue of good character is reflected in Aristotle’s famous dictum that “character may almost be called the most effective means of persuasion.”

Cicero noted much the same regarding basic morality, arguing that virtue was “the habit of the mind which makes us consistent in doing good.” If this seems too wooly, think of the doctrines in most faith traditions that require engaging in acts of service to others. Or consider the exemplary lives of Americans such as Martin Luther King, Madeleine Albright or Fred Rogers.

Aristotle’s ethical standards for an able advocate included the capacity for reasoning accurately, awareness of what is appropriate to a situation, and the mastery of language. Add Cicero’s recommendations that people worthy of our support cultivate goodwill, kindness, and benevolence. These ideas aren’t alien to us, but we seem lost in the maw of popular media that can distract us from sorting the honorable from the self-promoters.

There’s another an important twist here. In our era we tend to plant false flags that affirm loyalty to certain individuals, mistaking an act of continuous devotion as its own kind of moral absolute. Interestingly, both philosophers centered their discussions of communication ethics on the agent. Neither had much to say about loyalty as a core virtue: a revealing fact, given the high status we now give to a person who is—not infrequently—totally devoted to an ethically flawed person. Many seem to have developed a withered form of ethics based on a fixed allegiance. What remains is more transactional, and based more on the personal rewards of a settled mind set. Put another way, we make fewer demands that others be “virtuous,” settling instead on their believability. In this realm, public figures with social capital matter more rather than those with integrity. Indeed, a person’s notoriety may be their chief asset in dominating a cultural space.

Perhaps we no longer want to be put to the test of thoughtfully assessing a person’s character. Our awareness of others outside our immediate circle is often nominal and impressionistic. If Aristotle thought the high ethos of a person was set prior to their appearance, we tend to construct our truncated version of it on the spot. Vetting by using the standards of logic and evidence requires more effort than we are willing to give.

![]()

If here are pleasures in delivering anonymous and wounding responses, they make a mockery of the familiar cant that the “internet wants to be free.”

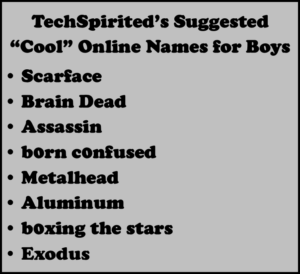

If here are pleasures in delivering anonymous and wounding responses, they make a mockery of the familiar cant that the “internet wants to be free.” The problem is that online pronouncements from individuals using pseudonyms are allowed. With exceptions, online protocols accept the kinds of false identities that were once associated with characters in spy novels working behind enemy lines. Typical are the monikers used by individuals who responded to a Slate.com story about the recent Boston bomb attacks a number of years ago. Slate was careful and responsible in its reporting. But as with most news sites, the individuals who signed on to make comments concealed their identities. Readers heard from “Celtic,” “ICU,” “ddool,” “roblimo,” “Dexterpoint,” “Lexm4,” and others. “Celtic,” for example, noted that the suspects were “Muslims,” expressing mock surprise that any of them would produce “terrorist actions.” “Dexterpoint” decried “lefties” who he imagined to be anxious to confirm that the terrorists were not Muslims. Slate’s policy has not changed.

The problem is that online pronouncements from individuals using pseudonyms are allowed. With exceptions, online protocols accept the kinds of false identities that were once associated with characters in spy novels working behind enemy lines. Typical are the monikers used by individuals who responded to a Slate.com story about the recent Boston bomb attacks a number of years ago. Slate was careful and responsible in its reporting. But as with most news sites, the individuals who signed on to make comments concealed their identities. Readers heard from “Celtic,” “ICU,” “ddool,” “roblimo,” “Dexterpoint,” “Lexm4,” and others. “Celtic,” for example, noted that the suspects were “Muslims,” expressing mock surprise that any of them would produce “terrorist actions.” “Dexterpoint” decried “lefties” who he imagined to be anxious to confirm that the terrorists were not Muslims. Slate’s policy has not changed.