To the question “Where was I?” a common reply is that we were probably “peripherally processing:” tuning out most that was said.

[A 2018 essay on a very helpful theory of message reception got the basic model right. But in hindsight I discovered that I didn’t more thoroughly consider how our busy lives force us to sacrifice the rewards of being fully engaged with a single challenge. Drifting away from a person’s words now seems like the norm. I suspect we only have the required discipline at peak moments of focus when we know that something important is on the line: everything from two pilots in a cockpit reviewing contingencies prior to what will be a difficult landing, to a journalist getting just one shot to ask a newsmaker a question. Too infrequently do we engage in this kind of critical awareness. Here’s an updated version of that piece with two key terms from a theory that offers useful language to access whether a receiver is fully engaged on a single task.]

Occasionally an idea in communication comes along that provokes the realization that it would not be possible to live without it. Good theories can help us see what is right in front of us. So, it is with a set of observations that fall under the name of Elaboration-Likelihood Model. The name might be a little off-putting. But as a framework for insights about how messages are likely to be received by others, the model is golden. It has been enormously helpful in various branches of the social sciences. We are in the realm of the theory when we wonder how we missed seeing or hearing a message that came our way. To the question “Where was I,” the answer is probably that you were focused on a challenging task or, more likely, tuning out most everything that came your way. Not paying adequate attention is a modern affliction.

Elaboration Likelihood Theory

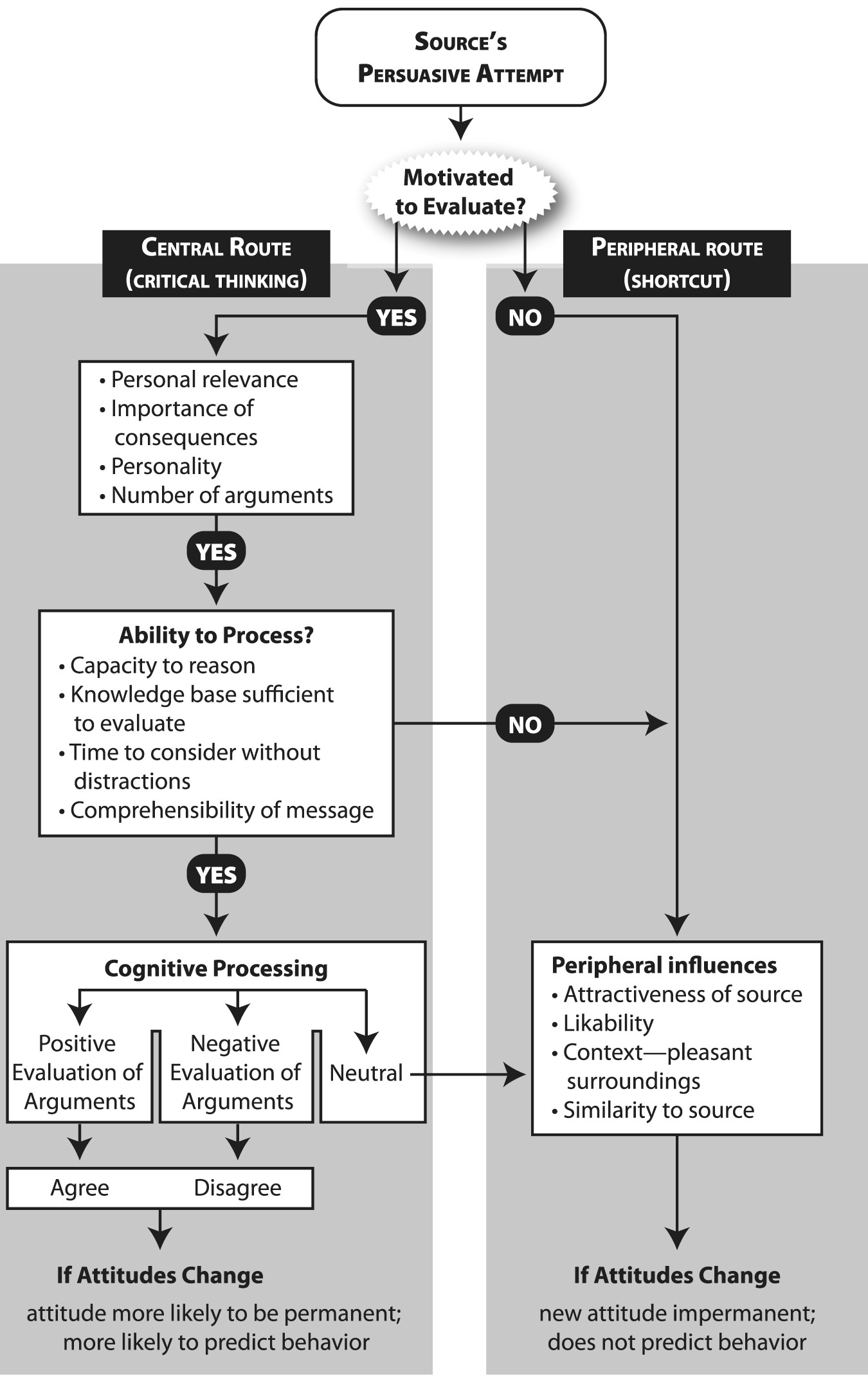

The framework first proposed by Richard E. Petty and John Cacioppo proposes that we think about the reception of messages as coming via one of two general pathways. Messages that are “centrally processed” are, by definition, the kinds that trigger a whole set of critical responses. These are claims and ideas readers or listeners think about. Their engagement means that they are more inclined to assess these assertions against what they know. Their beliefs or behaviors have been put into play and may change.

The model assumes that serious attempts at advocacy or involvement must gain a strong foothold in our consciousness. Those messages that get scant attention are said to be “peripherally processed.” A message like an advertisement or a casual request from another may wash over us quickly. We are not especially interested or motivated to hang on every word. And, as you would guess, the message is not likely to produce significant or lasting change. It has not created an impression that sticks.

The model assumes that serious attempts at advocacy or involvement must gain a strong foothold in our consciousness. Those messages that get scant attention are said to be “peripherally processed.” A message like an advertisement or a casual request from another may wash over us quickly. We are not especially interested or motivated to hang on every word. And, as you would guess, the message is not likely to produce significant or lasting change. It has not created an impression that sticks.

All of this may seem more or less obvious. But considering how much a person or audience cares is a worthwhile question. It asks if you can trigger enough attention and interest to have a chance at producing real effects. As labels, “Peripheral” and “Central Processing” are good ‘top-of-mind’ concepts. Keep them in your head as you parse out the amount of energy you want to invest in sending or receiving a message.

The model’s relevance increases every year as Americans recede into ever-deeper waters of message overload. We simply weren’t made to attend to what is now a routine exposure to many hundreds of messages every day. We may deceive ourselves into believing that we can multi-task and accurately consume all that is thrown at us. We can’t. Truth to be told, we’re not good multitaskers. Peripheral processing means that we will miss too much to feel bound by a specific request. It’s antidote is active listening.

Watch a skilled grade schoolteacher manage a class and you will see a survivor who knows that active listening and central processing are essential and hard won. It takes time, repeated attempts, aa lot of eye contact and follow up. When we get older, we are our own bad actors by endlessly staring at phones and multitasking. As we’ve noted before, none of us are good multitaskers. Multitasking is the gateway to incorrect directions, missed messages, misunderstandings and, finally, a growing frustration of being disconnected from people that matter.

Another person’s attention may be essential. But it is not easily given.

When you find yourself saying to a friend our spouse “I mentioned it yesterday; I’m sure I said it” we are likely recalling something that mattered much more to us than the person who was supposed to be listening. And, while we can get frustrated at the other’s inattention, we also need to cut them the slack by recognizing that communicating with a peripheral processor is a bit like shouting in the forest. The people close by may look like they have heard us. The Elaboration Likelihood model reminds us to have some doubts.

There’s also an interesting twist here. Someone who is fully engaged with their own thoughts—critically thinking them through—may not have much time for another’s extraneous conversation. Albert Einstein was supposedly forgetful. Was this was because he was engaged in the challenges of playing out the nuances of major insights like the theory of relativity? By now it is a cliché for an author to construct a character like the absent-minded professor: intensely focused on one thing, yet unable to take in the verbal clutter around them. That’s my excuse, even if no one no one lets me get away with it. But you can see the irony here: peripheral processing might be one consequence of central processing. The more we are locked into exploring a singular idea, the less we may be available to adequately receive the messages of others.

Of course, the model is more nuanced than I have presented. Wikipedia has a more complete overview of it. And models with only two reference points need to accommodate the likelihood of various gradients. But anyone who wants to break through the crust of a peripheral processor can start by considering several recommendations. First, repeat what you deem important. A tactful rewording of the message that you want another to retain may help. Second, give the peripheral-processing “forgetter” some slack. To deal with every message that comes to us is not possible. If we tried to do it, we would need a mental health intervention. To be sure, another person’s attention may be expected. But the requirements for sanity in an over-communicated society mean that it can’t be easily given. Finally, as a receiver, practice central processing. Repeat what you heard someone else describe. Take notes. Ask questions. Do whatever is required to fully give yourself over to their message.

![]()