Anyone thinking that a corrupt and out-of-control federal government is a one-off national disaster would do well to remember Mark Twain’s disgust with the “Gilded Age” of his era.

Americans are obviously alarmed at the chaotic dismemberment of the federal government and its norms in these early months of the Trump Administration. Reliable media resources like the Washington Post and New York Times are reminding us of Trump’s attempts to undermine constitutional limitations, and especially his use of the Presidency and its powers to generate income for his family and friends. The current fallout with Elon Musk makes it obvious that tech leaders have sought to win government contracts and punish potential competitors in nearly every industry, from automobiles to steel. Trump family businesses continue apace with efforts to solicit new real estate deals from Arab states and elsewhere, while using government decrees to restrict manufactured products traditionally supplied by former allies like Canada and Germany.

Anyone thinking that a corrupt and out-of-control federal government is a rare exception would do well to remember that Mark Twain’s well-named “Gilded Age: A Tale of Today” (1873) published in 1873 and featuring the same kind of grifting. Samuel Clemens as Mark Twain was a bitter critic of the superficial glitter that masked underlying social issues, highlighting the moral decay and the greed that characterized the era. To be sure, Twain later had his own investment and money-making schemes, mostly centered on printing and publishing. But along with the book’s co-author, Charles Dudley Warner, he viewed this period as a time of chaotic social upheaval, marked by rampant corruption, business speculation, materialism, and a vast contrast between the wealthy and the impoverished masses. As a recent PBS documentary about this period noted,

Anyone thinking that a corrupt and out-of-control federal government is a rare exception would do well to remember that Mark Twain’s well-named “Gilded Age: A Tale of Today” (1873) published in 1873 and featuring the same kind of grifting. Samuel Clemens as Mark Twain was a bitter critic of the superficial glitter that masked underlying social issues, highlighting the moral decay and the greed that characterized the era. To be sure, Twain later had his own investment and money-making schemes, mostly centered on printing and publishing. But along with the book’s co-author, Charles Dudley Warner, he viewed this period as a time of chaotic social upheaval, marked by rampant corruption, business speculation, materialism, and a vast contrast between the wealthy and the impoverished masses. As a recent PBS documentary about this period noted,

[T]he average annual income [for an American family] was $380, well below the poverty line. Rural Americans and new immigrants crowded into urban areas. Tenements spread across city landscapes, teeming with crime and filth. Americans had sewing machines, phonographs, skyscrapers, and even electric lights, yet most people labored in the shadow of poverty.

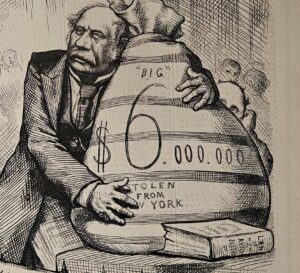

We may consider adopting the author of Huckleberry Finn and political cartoonist Thomas Nast as patron saints we can turn to as we suffer through the destruction of our once more-ordered politics. Twain hoped but never achieved the idea that Nast would go one speaking tours with him, drawing his his sour images of greed while Twain talked about the moral depravity of a growing class of plutocrats.

Twain joined a number of other Connecticut neighbors and New England thinkers in decrying the collapse of honest and compassionate leadership. In the words of biographer Justin Kaplan, he used the novel employing the “raw materials” of “disaster, poverty, blighted hopes, bribery, hypocrisy, seduction, betrayal, blackmail, murder and mob violence.” This “incredible rottenness,” he believed, filled every corner of American life. It left Twain with little hope that American politics could be set right. His literary peers were similarly aghast at the self-dealing and corruption that defined the era. Walt Whitman wrote that “the depravity of the business classes of or country is not less than has been supposed, but infinitely greater.”

Are we Beyond the Capacity for Self Government?

![]() Perhaps less known is that there are periods in his life when Twain was sour on even the idea of democracy. With the Civil War a recent memory, I would guess that his faith in the judgment of the South where he grew up was not high. And he was none too happy with his self-satisfied Hartford neighbors as well. It is worth remembering that as a younger man, and for just a few weeks, he was a member of the Confederate Army, until, as he tells it, he got bored.

Perhaps less known is that there are periods in his life when Twain was sour on even the idea of democracy. With the Civil War a recent memory, I would guess that his faith in the judgment of the South where he grew up was not high. And he was none too happy with his self-satisfied Hartford neighbors as well. It is worth remembering that as a younger man, and for just a few weeks, he was a member of the Confederate Army, until, as he tells it, he got bored.

The lesson of Twain’s colorful past is relevant to the question of whether the U.S. now has the human resources for effective and democratic self-government. The perceived power centers of our lives have been fragmented and taken up residence in our devices, with digital mesmerism leaving many of us with little energy to consider what part of this formerly great society we want to be a part of. As with Twain, all of us have to deal with unsavory political acts, hopefully finding redeeming values in our connections to families, sports and art. To paraphrase Friedrich Nietzsche, and to Twain’s credit, ‘We have art in order not to die from ugly social truths.’