We assume we are active and powerful because our language lets us imagine it.

Presidents easily muster fantasies of mastery and control. It is a habit to overestimate their abilities to manage events. My two over-the-top examples in this Hall of Fictions includes Donald Trump’s recent claims that destroyed Gaza along the Mediterranean can be turned into a vacation spot like the Riviera, and that Canada will be the 51st State. Trump always overpromises and then retreats. Even so . . .

Presidents easily muster fantasies of mastery and control. It is a habit to overestimate their abilities to manage events. My two over-the-top examples in this Hall of Fictions includes Donald Trump’s recent claims that destroyed Gaza along the Mediterranean can be turned into a vacation spot like the Riviera, and that Canada will be the 51st State. Trump always overpromises and then retreats. Even so . . .

Rhetoricians like to say that language has its way with us. The phrase is meant as a reminder that everyday language steers us to conclusions that usually promise more than we as individual agents or nations can deliver. Word choice can easily create perceptions that can make the unlikely more likely, the improbable possible, and a fantasy as an imagined outcome. Such is the nature of linguistic determinism. We can tie a wish to an action verb, and we are off and running, creating expectations for things that probably will not materialize. Who knew that simple verbs like “is” and “will” can be taken as fate, when they are more likely phantoms of deceit? Blame our overly-deterministic language.

Stephen Biddle and Jacob Shapiro indirectly made this point several years ago in The Atlantic when they noted that civil wars must usually “burn out” from the inside. A civil war such as Syria’s or Sudan’s might take years to wind down; an outcome outsiders can’t change very much.

Our verbs may sing their certainty, but forces we can’t predict are going to produce their own effects.

What seems inescapable is that committing ourselves to the control![]() of complex political forces is too easy. That is something we’ve come to know all too well since the Vietnam era, reconfirmed more recently in Afghanistan, Iraq and Ukraine. The military and social problems associated with nation-building are unforeseeable, giving us under-considered reasons to get lost in the neon glow of action verbs.

of complex political forces is too easy. That is something we’ve come to know all too well since the Vietnam era, reconfirmed more recently in Afghanistan, Iraq and Ukraine. The military and social problems associated with nation-building are unforeseeable, giving us under-considered reasons to get lost in the neon glow of action verbs.

We construct the world as a web of causes and effects. It’s natural that we will place ourselves and our institutions in the driver’s seat. We assume we can be in charge because our language so easily lets us imagine it. Blame our overly-deterministic language, along with the hubris that comes with being a preeminent military power. Both set up tight effects loops that seem clear on the page but elusive in real life.

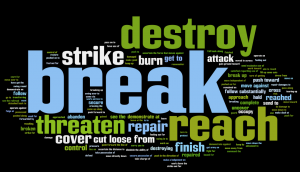

If we put individual culprits in a lineup they all look more or less innocent: verbs like affect, make, destroy, break, causes, starts, produce, alters, triggers, controls, contributes to, allows and so on.

In the right company these can be companionable terms. But let them loose within the rhetoric of a leader determined to make his or her mark and they can turn lethal. Fantasies of power and control impose more order on human affairs than naturally exists. They depend on verbs that flatter us by making us active agents, usually with all kinds of “unintended effects” we only discover later.

This sense of predictability is ironically aggravated by our devotion to the scientific![]() method. As Psychologist Steven Pinker has observed, we can’t do science without buying into the view that we can identify first causes. That’s surely fine for discovering the origins of a troublesome human disease. But even though this logic is diffused through the culture, it cannot hold when we immerse ourselves in the infinite complexities of human conduct. Discovering the reasons and motivations of others is far more difficult. Add in entities such as nations, political parties and tribes, and first causes are often unknowable. And so strategic calculations based on efforts to influence or control events are bound to produce disappointment.

method. As Psychologist Steven Pinker has observed, we can’t do science without buying into the view that we can identify first causes. That’s surely fine for discovering the origins of a troublesome human disease. But even though this logic is diffused through the culture, it cannot hold when we immerse ourselves in the infinite complexities of human conduct. Discovering the reasons and motivations of others is far more difficult. Add in entities such as nations, political parties and tribes, and first causes are often unknowable. And so strategic calculations based on efforts to influence or control events are bound to produce disappointment.

It’s a great paradox that we are easily outgunned by the stunningly capricious nature of human responses. Take it from someone who has spent a lifetime studying why people change their minds. We have models, theories, tons of experimental research and good guesses. But making predictions about any specific instance is almost always another case of reality crushing hope. We may be able to say what we want, giving eloquent expression to the goals we seek. And our verbs will predictably sing their certainty, but language is always going to produce its own surprises.

He says he is doing this for others. But his vindictive acts seem to spring from a persecution complex that turns the idea of a unifying president on its head.

He says he is doing this for others. But his vindictive acts seem to spring from a persecution complex that turns the idea of a unifying president on its head. Retribution is easily paired with the idea of hate, the engine that powers the desire to give a wounding response. In turn, this adds a level of worry within targets fearful of the negative consequences that may result. Alaska Republican Senator Lisa Murkowski recently reported her own fear of the consequences for doing her legislative duties. That is a terrible omen, and surely the reason we have a servile GOP.

Retribution is easily paired with the idea of hate, the engine that powers the desire to give a wounding response. In turn, this adds a level of worry within targets fearful of the negative consequences that may result. Alaska Republican Senator Lisa Murkowski recently reported her own fear of the consequences for doing her legislative duties. That is a terrible omen, and surely the reason we have a servile GOP.