Language has a kind of expressive power that numbers cannot match. So why has so much of our research in the humanities and social sciences spurned verbal description in favor of numerical measures?

Humans are a diverse lot. Even so, research conventions dictate that explorations of the many facets of the human condition should now be represented in numbers: usually percentages, raw totals, averages, or deviations from the average on single or multiple scales. Variables are identified only if they can be operationalized and counted in some way. And while these numerical summations will sometimes give us a useful “big picture” view, they frequently distract us from seeing the enormous multiplicity that exists within human groups. This is heresy against current orthodoxy. But hear me out.

In my own field of communication such analyses sometimes gain a thin and partly unearned patina of rigor and exactitude. Speaking broadly, they can easily become fraudulent when they are meant to represent complex internal states: for example, levels of empathy, degrees of emotion or sympathy, or when even when representing acceptance of a thing, person, or idea. Should we be surprised that even something as straightforward as political polling is noticeably unreliable?

Governments, organizations, and publishers love “data.” Data sets are almost a prerequisite for any claim of academic seriousness. They appear to be unassailable. Dissertation advisors routinely steer their students to work up pages of numerical summaries that may say little about the uniqueness of individual cases. Tables, scales and percentages buy a degree of credibility. As the misplaced aphorism goes, “numbers don’t lie.” But of course they do. The appearance of a precise numerical measurement is probably the most important trope in the rhetoric of the social sciences, even when an individual measure would be more useful “opened up” with illuminating descriptions or representational stories.

Older and more discursive modes using ordinary language were once favored by an impressive group of mid-century thinkers systematically exploring cultural and individual markers. Among many others, Erving Goffman, Kenneth Burke, George Herbert Mead, and David Reisman enabled landmark advances in the humanities and social sciences. Their of use of dense description to explore underlying patterns of language usage and behavior sustained a broad range of explorations for many. As one modest scholar captivated by their probes, I could barely work fast enough to keep up with just a few of the their intellectual pathways. Their discursive modes of writing invited explorations of useful ambiguities, exceptions, and insights triggered by illuminating metaphors.

It is interesting to note that specificity of description is how narrative in all forms treats social issues. As the sociologist and rhetorician Hugh Dalziel Duncan noted, drama allows us to be “objects to ourselves.” But it should not fall only to the dramatist to witness and report another’s lived experience. Modern scholarship often needs the specificity of an individual case. One advantage is that a single study can explore an individual’s perceptions. Since these forms of awareness can vary across a population, they do the honor of treating a subject on their own terms.

Single or limited cases can also illuminate patterns evident in a portion of an entire class. Alexandra Robbins’ recent book focusing on a handful of elementary school educators (The Teachers, 2023) is surely more illuminating about current challenges in our public schools than a lot of the opaque data published every year.

![]()

Language is expressive; numbers are not.

I encountered the useless and diminished value of numbers in a study I completed several years ago that looked broadly at sound and hearing (The Sonic Imperative, 2021) The capacity to hear requires a broader range of reference points than with other kinds of projects. Sound has its own physics, which can be represented in units of volume (decibels) or pitch (frequency). But when looking at human perceptions of sound, we must consider individual and unique variations. The gateways to every human mind are distinctive. So, our perceptions of sound, or food, or images must bend to the subject. Even while we have acquired metrics that identify many features of a person, sensory complexity is best approached phenomenologically: as experiences we can explore, but are rightly owned by the individual.

Returning to the case of sound, we surely need the precision of acousticians, engineers and others who measure and document patterns and boundaries of auditory content. We have the tools and electronic instruments to make sound discussable. And in musical notation we also have an awkward but functional way to visually represent the ephemeral artifacts of organized sounds. But a copy of a musical score is not what passes through the ear. If we want to say more about that process, we all must be phenomenologists, applying a range of descriptive forms: self-reports, dense descriptions of others, and the judgments of academic critics who have devoted their lives to appreciating what we may not notice.

To cite a specific case, some researchers have tried to measure and set out gradations of the human response of empathy, which can be triggered by an image, sound, or a simple conversation. But using metrics to describe so personal an effect is a fool’s errand. We have better tools on display in the seminal works of many cultural critics. Academia would frequently do well to give more credibility to these adequately curated impressions, resisting the urge to flatten every idea into a one-dimensional category that can be numerically expressed. Language is expressive; numbers are not. Like music on the page, numerical tallies of all sorts are mostly dead on arrival until they can be converted back into the living form they are only meant to approximate.

![]()

In a pluralistic culture, public officials have a moral duty to understand that their magical thinking about what constitutes a full life cannot be binding on all.

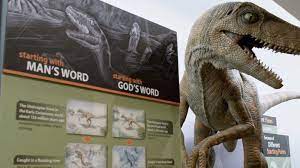

In a pluralistic culture, public officials have a moral duty to understand that their magical thinking about what constitutes a full life cannot be binding on all. The literalism of the evangelical fringe has pushed its followers into a kind of denial of the physical world that would seem impossible. But Johnson made it all the way through law school holding on to a version of “young earth creationism” that ignores the many new and impressive truths of paleontology, geology, meteorology, physical cosmology and oceanography. And what about carbon dating? A literal reading of the Bible’s Book of Genesis that posits that our earth is only several thousand years old is not “faith” in a richer spiritual sense, but the willful enactment of deceptions clothed in a rhetoric of piety. Old Testament language is definitive and hortatory. It is reflected in Puritan language that shows the same kind of rigid certainty: a form of religious thinking that was even too much for evangelist Pat Robertson.

The literalism of the evangelical fringe has pushed its followers into a kind of denial of the physical world that would seem impossible. But Johnson made it all the way through law school holding on to a version of “young earth creationism” that ignores the many new and impressive truths of paleontology, geology, meteorology, physical cosmology and oceanography. And what about carbon dating? A literal reading of the Bible’s Book of Genesis that posits that our earth is only several thousand years old is not “faith” in a richer spiritual sense, but the willful enactment of deceptions clothed in a rhetoric of piety. Old Testament language is definitive and hortatory. It is reflected in Puritan language that shows the same kind of rigid certainty: a form of religious thinking that was even too much for evangelist Pat Robertson.