Fighting back against our modern thought-police

A year ago it was apparent that the headwinds against progressive schooling were getting stronger. This post written at the time reflects that problem. Since then, a group of mostly of states have sought to legislatively impose all sorts of restrictions on teachers, professors, librarians and school boards. As I noted then, we could reach a point where scholars and teachers may need to pass over job offers because of draconian state laws. Reduced academic freedoms and free expression are central to the academic workplace.

In particular, Florida, Alabama and Texas have passed legislation that would prohibit academics from teaching about the social and political histories of the nation. Many would also not allow discussions or facilities provided for trans students.

We do not yet know how many of these hate laws will withstand court scrutiny. But the very thought should send shudders down the spines of those familiar with the attempts of German Fascists to purify their society of “decadent” art and “alien” ideas. Most of the homegrown pinheads proposing this censorship may have never learned that the United States and the West did the world a favor by sheltering a important German academics fleeing to safety from authoritarians. Walter Benjamin, Theodor Adorno, Else Frenkel-Brunswik and Herbert Marcuse are only a few intellectuals that found their way to the United States. They fled the Nazi’s thought police who found their teaching and religious beliefs alien to the culture. All focused their scholarship on culture and society, making advances in American explorations of philosophy, psychology, sociology and cultural analysis. Indeed, Adorno and Frenkel-Brunswik’s explorations of “The Authoritarian Personality” remains relevant in this era of populist-fascist dictatorships. What they described as theory we now understand as fact.

We do not yet know how many of these hate laws will withstand court scrutiny. But the very thought should send shudders down the spines of those familiar with the attempts of German Fascists to purify their society of “decadent” art and “alien” ideas. Most of the homegrown pinheads proposing this censorship may have never learned that the United States and the West did the world a favor by sheltering a important German academics fleeing to safety from authoritarians. Walter Benjamin, Theodor Adorno, Else Frenkel-Brunswik and Herbert Marcuse are only a few intellectuals that found their way to the United States. They fled the Nazi’s thought police who found their teaching and religious beliefs alien to the culture. All focused their scholarship on culture and society, making advances in American explorations of philosophy, psychology, sociology and cultural analysis. Indeed, Adorno and Frenkel-Brunswik’s explorations of “The Authoritarian Personality” remains relevant in this era of populist-fascist dictatorships. What they described as theory we now understand as fact.

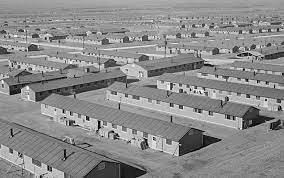

The “problem” that social conservatives think they are addressing includes ostensibly “dangerous” leftist ideas, and the teaching of what most misunderstand as “critical race theory:” a phrase that triggers fantasies that chain out past what are useful historical and theoretical probes. The goal is to prohibit teachers in history and the social sciences from confronting the fact of American racism first institutionalized with slavery and then embedded in nearly every corner of our national life. Tina Descovich, of “Moms for Liberty” sets out very narrow guardrails: “To say there were slaves is one thing, but to talk in detail about how slaves were treated, with photos, is another.”

Really?

No one alert to the challenges facing modern nations can ignore the enormous effect that racial and religious bigotry has had on its victims. The most advanced societies have made amends. But we are still easily upside down if the classroom is subjected to gag rules imposed by non-expert and misinformed politicians. Legislating away American attempts at necessary reckonings with the past is truly a fool’s errand. And ghosting services for gay and trans citizens is its own nightmare. Legislators would do well to acquaint themselves with Nazi programs in the 1930s and 40s to purge public spaces of supposedly “degenerate art,” including pieces by Picasso, Henry Moore and Jewish painters. Some of their work was officially hidden away, even though societies need the revitalization of those who may seem to be on the fringes.

The best educational communities do not impose curricular guidelines that would muzzle the insights of authentic scholarship. If it were possible to do so, such limits would empty out academia of its best and brightest in the fields of media theory, American history, modern criticism, American literature, philosophy, sociology, ethnic and religious studies. It’s one thing for a church or private organization to impose a-priori “doctrines,” that allow only narrow pathways for exploration. It’s quite another for non-expert legislatures or school boards to set rules that would restrict the free discovery of ideas that is the very reason for a university. We could reach a point where professional bodies representing various disciplines may need to issue warnings to teachers and scholars to reject job offers in states that have decided to turn their backs on the hard truths of the American experiment.

![]()