We have become a culture of grievance.

Maintaining healthy life-affirming personal relationships takes time and effort. Add in layers of complexity in dealing with our digital daisy chains, and we may begin to notice that the need to fix problems they create can outpace their advantages. Can we still have time for others if we are pushed into a reactive mindset that leaves us exhausted?

This does not apply to miraculous medical advances or life saving inventions. But it seems like everything else–from online banking to mastering a smartphone apps–is less easily mastered. GPS is an amazing advance. Using it for directions on a portable device, not so much. Or consider that a busy adult may need to appeal a denial of an insurance claim, or understand a wordy user agreement for a “one time offer,” or find workarounds to a firewall that denies information they are entitled to know. At least for this digital immigrant, examples accumulate as a typical day moves on. I recently gave up on doing a review of a journal article that I promised to complete after a run-in with a Fort Knox of gates: the requirement to find yet another new username and password to access the piece, then a pin I did not know, and then the appearance of a prompt insisting that I would need to reset some preferences in my browser. Only then could I cast my eyes on the article that carried no national security secrets. Or consider the widespread use of digital phone trees and closed option customer service recordings that delay us from reporting a specific problem or a simple request. These are typical with our cable supplier, which thinks it is in the communication business. Though it reliably collects its monthly charges, it is not. Any requests coming from our end are the rough equivalent of an airline routing a Twin Cities passenger through Miami.

What I am describing produces a consumer funk that settles into a cycle of grievances. Almost everyone seems to have the same complaints about broken service agreements or inert organizations that cannot be roused. With the so-called “internet of things,” common household items ranging from robot vacuums to washing machines are sold as “doing more” because of their added and unnecessary digital capabilities. We set them up with all the necessary strings that will later become hopelessly tangled: a new “account,” usernames, passwords, and numerical codes which may or may not match up with the platforms we are using. I am waiting for the day when a request for Alexa to turn on household lights will instead open our neighbor’s garage doors or turn on their vacuums. Like many, I have an account notebook in a mostly failed effort to keep a record of all my digital breadcrumbs. But they have clearly scattered across the pages, leaving indecipherable and crossed out passwords that resemble cave paintings covered in graffiti.

None of these single events are seriously egregious. But they can easily accumulate, leaving us in a state of festering grievance. Social media like to show us male and female “Karens” who have left the world of the sane, having been provoked into in a state of barely containable rage. Most seem to have lost their skills for interpersonal adaptation. Their explosions also spill out into in our polarized politics, where polling suggests that many less affluent Americans carry perpetual grievances about being left out of the American dream. Was Donald Trump channeling these thoughts with his surprising inaugural reference to “American carnage?”

What has changed in part is the nature of problem-solving and troubleshooting. In the analogue world of the last century various schemes for fixing things were sometimes within the grasp of a creative teen or adult. Getting a clear picture from a television might have come from simple manipulations of an over-the-air antenna. A new vacuum tube might revive an ailing radio. Now, obviously, our entertainment arrives in electronic lockboxes that turn us into supplicants. Instead of the tinkering mindset fostered in earlier epochs, we must become compliant followers of their protocols. I suspect recent legislative “right to fix” initiatives have come too late.

How do we stay sane and upbeat against the daily pounding we take from increasingly arcane channels of the organizations we need to do business with? At what point does this added complexity drain us of the energy to meaningfully deal with others in simple interpersonal space? Add in the problem of constant dysconnectivity and it is easier to challenge the assumption that digital tools are the fastest routes to restoring pieces of our lives that have fallen apart.

We can escape a doom cycle of continuous grievance if we use the tools that are already around us, perhaps:

- a vacation that that lets us get away from our broken connections.

- immersion in long form media—a novel, a film, or an hour-long performance of music.

- meditation in whatever form works

- an extended mode of physical movement on foot, on a bicycle, or on the water, all of which can put us back in the unmediated world that our bodies were made to know.

![]()

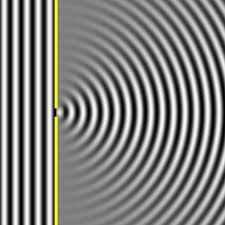

In early 2022 news reports in the New York Times and elsewhere indicated that federal efforts to explain the Havana syndrome focused on identifying common sets of medical and psychological conditions that would allow more comparative study of cases arising from high stress settings. Interestingly, there were similar reports of illness from Americans stationed in Austria and China, among other locations. The task was to sort out the normal stresses that come with a new foreign assignment from specific cases centered on complaints of headaches, nausea, ringing in the ears, and other conditions.

In early 2022 news reports in the New York Times and elsewhere indicated that federal efforts to explain the Havana syndrome focused on identifying common sets of medical and psychological conditions that would allow more comparative study of cases arising from high stress settings. Interestingly, there were similar reports of illness from Americans stationed in Austria and China, among other locations. The task was to sort out the normal stresses that come with a new foreign assignment from specific cases centered on complaints of headaches, nausea, ringing in the ears, and other conditions.