If you have work to discuss with others, think twice before turning a meeting into a bad video.

All of us are discovering the mixed experience of connecting with others via one or another video application. The default has usually been a connection through Zoom, FaceTime or Skype. But if you really want to discuss ideas rather than “chat,” you may have a better discussion without staring at a screen that looks like a time-warp version of your high school yearbook.

A screen filled with faces is not only a distraction, there is a solid theoretical reason why video undermines discussion. As early as the 1950s the great thinker Susanne Langer explained that “presentational media”–meaning media forms that emphasize images– easily dominate over “discursive” forms that communicate by what has been said. Ideas require more cognitive effort than simple images.

The problem is that our era preferences images. Zoom is a prime example. It’s fine for visiting too rarely seen grandkids or family. But it’s far less satisfactory explaining complex thoughts, policies or values. You’ve maybe had better luck, but my Zoom audio levels are terrible and obviously operating with very little bandwidth. By contrast, the conference call system I’ve been using for classes puts a person’s voice at close range, not four feet away as picked up by an afterthought microphone. It’s just easier to hear people when their ideas and inflections are more clearly rendered. It would not add much to see my students in their virtual phone booths. (I cheat a little: they also have pre-loaded PowerPoints to follow at the same time.)

As to the Supreme Court: most of the attention in these sessions is where it should be: on the quality of arguments and evidence.

It’s no surprise a preference for audio only is what the Supreme Court has recently chosen. They are communicating via a simple conference call system. Granted, the lawyers answering questions would surely like to read the body language of the Justices. But most of the attention in these sessions is where it should be: on the quality of arguments and evidence.

I’m not alone in thinking that we have oversold turning teaching into television show of reaction shots. Writing recently in the New York Times (May 4), Kate Murphy writes that others have noted how the steam has gone out of their meetings or teaching: undermined by out of sync sound, bad pictures, and the inevitable challenges of forcing all participants to go into an awkward self-presentation mode . Never mind the interruptions from unwanted intruders.

Not surprisingly, audio-only phone use is way up. It’s also finally being recognized as an often overlooked form of telehealth, especially in the mental health field. A lot of Americans are sensing that there is less need to see the people they want to talk to.

To be sure, communicating by phone or video is far from perfect. As most of us are discovering everyday, we are hard-wired to connect in real time and real space. And while there are times when it is great to see others, if you have substantive work with others to complete during this period of self-isolation, think twice before turning a meeting into a bad video.

![]()

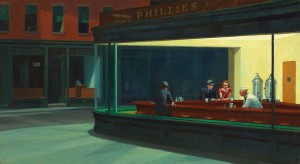

The present moment has created more self-isolation than most would like. We know what it means to be alone with one’s own thoughts. Chatter with others may be in short supply. But our consciousness can easily take the chatter inside. We may share a common culture and lineage, and we can build bridges to each other, but can our reservoirs of self-reflection ever be made transparent?

The present moment has created more self-isolation than most would like. We know what it means to be alone with one’s own thoughts. Chatter with others may be in short supply. But our consciousness can easily take the chatter inside. We may share a common culture and lineage, and we can build bridges to each other, but can our reservoirs of self-reflection ever be made transparent?