Maybe it is enough to revel in the miraculous achievements of a larger-than-life figure.

Biographer Nell Painter remembers working on a study of the former slave and abolitionist, Sojourner Truth, who led a remarkable life of advocacy over a period spanning the mid-1800s. But several years ago Painter told a C-Span interviewer that her “closeness to me receded” as she worked her way deeper into Sojourner’s life. She respected her subject to the end, but finally doubted they would connect in a conversation. Sometimes the great and good are better left to be appreciated for works in their time. Pick the right moments from our own lives and we can all look a little strange to future generations.

Biographer Nell Painter remembers working on a study of the former slave and abolitionist, Sojourner Truth, who led a remarkable life of advocacy over a period spanning the mid-1800s. But several years ago Painter told a C-Span interviewer that her “closeness to me receded” as she worked her way deeper into Sojourner’s life. She respected her subject to the end, but finally doubted they would connect in a conversation. Sometimes the great and good are better left to be appreciated for works in their time. Pick the right moments from our own lives and we can all look a little strange to future generations.

If this happens with even a pivotal and influential leader, I wonder if there is a general pattern that dictates that a hero who triggers the writing or reading of a full biography will look a little less amazing after sustained attention.

Over many years of reading I’ve sensed this effect, sometimes because of documented lapses of judgment that began to accumulate. More or less honest chronicles of another life are bound to bring even the most lauded subject back to earth. Clearly, biographies ‘humanize’ their subjects.

Reading about another’s life can rise from the simplest of motives. We want to know more about how someone pieced together an exemplary existence. What luck or brilliance worked to their benefit? What friends or associates were influential, or lucky to have them in their lives? These kinds of questions lead me to books written by or about Joan Didion, Griffin Dunne, Frank Sinatra, Woodrow Wilson, Steve Jobs, Riccardo Muti, Dimitri Shostakovich, Oliver Sacks, Jim Henson and many others. Even at the hands of a first-rate biographer, and perhaps because of the writer, some luminaries can lose their luster. In a few cases I’ve encountered enough documented boorishness to happily put the book aside. In our current moment we probably don’t learn as much from someone’s character faults. We have Donald Trump for that. I take the fickle reader’s option of moving onto something that is likely to be more affirming.

Reading about another’s life can rise from the simplest of motives. We want to know more about how someone pieced together an exemplary existence. What luck or brilliance worked to their benefit? What friends or associates were influential, or lucky to have them in their lives? These kinds of questions lead me to books written by or about Joan Didion, Griffin Dunne, Frank Sinatra, Woodrow Wilson, Steve Jobs, Riccardo Muti, Dimitri Shostakovich, Oliver Sacks, Jim Henson and many others. Even at the hands of a first-rate biographer, and perhaps because of the writer, some luminaries can lose their luster. In a few cases I’ve encountered enough documented boorishness to happily put the book aside. In our current moment we probably don’t learn as much from someone’s character faults. We have Donald Trump for that. I take the fickle reader’s option of moving onto something that is likely to be more affirming.

It is easy to see why some distance opened up between Painter and her subject, or why I never made it to the final pages of biographical details of Elon Musk, Frank Lloyd Wright or Griffin Dunne. It is certainly not just the subject’s fault that chapters of their documented existence show a person that might be a bore, even if we had the chance to share a lunch with them. We all have our stories. Even so, it can be a long slog to follow a narcissist through a 500-page history of their personal and professional experiences.

There is also the very real chance that a biographer is a bad match for their subject, incapable of doing justice to the life they sought to illuminate. Think of Kitty Kelley’s unauthorized and widely criticized biography of Frank Sinatra (1986). In sharp contrast, David Maraniss seemed to be a good match for his biography of the younger Bill Clinton, First in His Class (1996). Maraniss marveled at how this quick study was able to so easily connect with others. The documentation of these instances was compelling enough to shape my research for several years, growing into a book-length study (The Rhetorical Personality, 2010).

There is also the very real chance that a biographer is a bad match for their subject, incapable of doing justice to the life they sought to illuminate. Think of Kitty Kelley’s unauthorized and widely criticized biography of Frank Sinatra (1986). In sharp contrast, David Maraniss seemed to be a good match for his biography of the younger Bill Clinton, First in His Class (1996). Maraniss marveled at how this quick study was able to so easily connect with others. The documentation of these instances was compelling enough to shape my research for several years, growing into a book-length study (The Rhetorical Personality, 2010).

Maybe it is enough that figures like Didion or Sinatra had such miraculous talents that their work is reason enough to be an admirer. When life happens, its myriad details can easily get messy.

There is another issue that may arise more from the reader than the original writer. We live in an age when many of us are living through episodes of what is sometimes called “moral injury.” This occurs when a person is forced to witness physical or psychological atrocities. Writing about political influence was most of my life’s work, possibly leading to the development of a habit of quitting a study about a political leader who exhibited massive failures of character. I seemed to have had my fill. Perhaps a more analytic reader than I would persevere and be the better for it.

![]()

In many places incidental or ambient noise hovers at around 45 dB, or the equivalent of several household appliances running. But it can quickly go higher if a person is located in the vicinity of an airport or a busy highway.

In many places incidental or ambient noise hovers at around 45 dB, or the equivalent of several household appliances running. But it can quickly go higher if a person is located in the vicinity of an airport or a busy highway. Bank Park has 1400 loud speakers hovering in its packed seven-tier grandstand, enough to encourage any person in love with stillness to escape with a homerun over the center field wall. Granted, no one wants a silent sports venue, or a concert where the reactions of listeners are not part of what should be a contagious and magical experience. But it also seems apparent that some among us are careless in allowing our aural pollution to bleed into another’s personal space. You know the common culprits: fake low-fi bass spilling out of a car and onto nearby streets and sidewalks, or the pretend power represented in noisy after-market mufflers hanging from Honda Civics or Harley Davidsons.

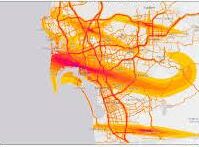

Bank Park has 1400 loud speakers hovering in its packed seven-tier grandstand, enough to encourage any person in love with stillness to escape with a homerun over the center field wall. Granted, no one wants a silent sports venue, or a concert where the reactions of listeners are not part of what should be a contagious and magical experience. But it also seems apparent that some among us are careless in allowing our aural pollution to bleed into another’s personal space. You know the common culprits: fake low-fi bass spilling out of a car and onto nearby streets and sidewalks, or the pretend power represented in noisy after-market mufflers hanging from Honda Civics or Harley Davidsons. Perhaps the best explanation for rethinking the intrusion of noise in our lives was offered by Les Blomberg of the Noise Pollution Clearing house, who imagined what it would be like if we could see the trail of noise we leave in our wake. It is a wonderful insight. In this image, the acoustic mess we sometimes make would look like piles of refuse or spattered paint tossed into the paths of others.

Perhaps the best explanation for rethinking the intrusion of noise in our lives was offered by Les Blomberg of the Noise Pollution Clearing house, who imagined what it would be like if we could see the trail of noise we leave in our wake. It is a wonderful insight. In this image, the acoustic mess we sometimes make would look like piles of refuse or spattered paint tossed into the paths of others.