This administration wanted us to be repelled by values that were honored just days before.

For decades I worked in a professional environment that placed a lot of faith in honoring the ideas of diversity, equity and inclusion (DEI). For most of my years in college teaching these were part of the catechism of values to make higher education available to as many students and faculty as possible. We wanted more diverse students to choose our program. And we knew in the 70s that more women should be part of the faculty. Living by these standards was not always easy, but evidence of progress was all around us: the positive symbolism of an African American President, a woman taking over as head of the country’s largest automobile maker, and a revolution in the number university presidents, deans and provosts with diverse backgrounds. All were proof that higher education and the managers of innovative groups everywhere were no longer a monoculture.

Who knew that in a few more years that on January 20th of this year the nation would suddenly be asked to abandon these progressive ideals that made these changes possible, This administration wanted us to be repelled by values honored just days before, not to mention an iconic statue sitting in the harbor in front of Donald Trump’s hometown.

Who knew that in a few more years that on January 20th of this year the nation would suddenly be asked to abandon these progressive ideals that made these changes possible, This administration wanted us to be repelled by values honored just days before, not to mention an iconic statue sitting in the harbor in front of Donald Trump’s hometown.

Now, this government is centered on white guys and a few women seemingly selected by Trump for their fashion-magazine looks. I can imagine storage rooms in corporations stacked floor to ceiling with unused copies of employee training materials with titles like Fostering Diversity in the Workplace or The Multicultural Corporation. Could the implicit racism of this destructive change be mitigated if we shifted the language to celebrate “differences,” “fair play” and “cultural variety?”

Positive values can reside in good people, even when their traditional signifiers have been stolen.

When I first heard the pronouncement against DEI–followed so far with the termination of 120,000 federal workers–I thought it was a joke: akin to banning positive expressions about Santa Claus, puppies, or landmark civil rights cases. But the negative reactivity of the new administration is deadly serious and spreading. We know we are on a slippery slope when politicians think they can take ownership of traditionally eulogistic words and simply redefine them as dyslogistic. The mistake of confusing words with thoughts is a fool’s idea of governing, resulting in governments like Florida’s, where language, curricula and books are already censored. Thankfully, positive values can reside in good people, even when their traditional signifiers have been stolen.

When I first heard the pronouncement against DEI–followed so far with the termination of 120,000 federal workers–I thought it was a joke: akin to banning positive expressions about Santa Claus, puppies, or landmark civil rights cases. But the negative reactivity of the new administration is deadly serious and spreading. We know we are on a slippery slope when politicians think they can take ownership of traditionally eulogistic words and simply redefine them as dyslogistic. The mistake of confusing words with thoughts is a fool’s idea of governing, resulting in governments like Florida’s, where language, curricula and books are already censored. Thankfully, positive values can reside in good people, even when their traditional signifiers have been stolen.

This all seems so dystopian and retro. It is no surprise that golf next to a golf cart is the president’s game, or that his wife stays mostly out of sight, or that his country club decorated in the gothic style of Sunset Boulevard (1950) is his preferred setting. Even the temporary co-president of Elon Musk with roots in white South Africa has become an ersatz Norma Desmond who no one wants to see. I expect a new Executive Order may yet come to affirm all of this patriarchy by making Old Spice the official national scent, along with a preferred diet of a sandwich of white meat with mayonnaise on white toast.

In spite of the abundance of pale rich guys milling around the White House, beyond Washington there is a more inclusive representation of talented folks who still sustain so many successful institutions of this country. Thankfully, Emma Lazarus quoted at the base of the Statue of Liberty never imagined that the nation would ‘Deport the tired, the poor, and the huddled masses yearning to breathe free.’

![]()

At the Oval Office meeting the President took the opposite position of the one urged by Marco Rubio. Rubio suddenly fell silent. As the Guardian reported, “The image of a sullen Rubio quickly went viral online, with one social media user dubbing him ‘the corpse on the couch.’”

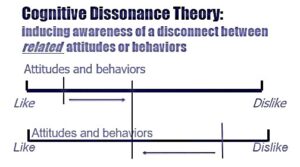

At the Oval Office meeting the President took the opposite position of the one urged by Marco Rubio. Rubio suddenly fell silent. As the Guardian reported, “The image of a sullen Rubio quickly went viral online, with one social media user dubbing him ‘the corpse on the couch.’” There are many possible refinements and variations on this model, but even in its simplest form it offers a theory of how our attitudes can change. Festinger was also wise enough to never underestimate our willingness to deny a contradiction.

There are many possible refinements and variations on this model, but even in its simplest form it offers a theory of how our attitudes can change. Festinger was also wise enough to never underestimate our willingness to deny a contradiction.