The song “To My Old Brown Earth” was actually written by Pete Seeger in 1958, after the death of a friend. But for all of us with an awareness that we would someday lose this beloved man, the song was the perfect eulogy for Pete himself.

We usually assume that language has a specific and stipulative function to communicate directly and without adornment. But that’s obviously an incomplete view. Words set to music often have more power over us. The ear so readily learns to love the nondiscursive forms of organized sound. It follows that meaningful ideas underscored by the right music can be transcendent: actualizing feelings that might otherwise be out of reach.

As the Greek poets and others like Walt Whitman used the term, a “song” can be a kind of spoken elegy. His Song of Myself from Leaves of Grass (1855) is a meditation on his own young life and its possibilities. In his case, the music was wholly in the words, even though others like the composer Ralph Vaughan Williams created stunning soundscapes inspired by them. Williams’ massive A Sea Symphony (1910) soaks us in the sense memory of being at the edge of the water.

In our more prosaic uses of “song” today, the music is more literal, and the words are often forgettable. But not always. Early in the last century Oscar Hammerstein was writing music for the theater that fully exploited the power of lyrics to carry the emotional impact of a story. There would be no embarrassing opera librettos for him. The words of Showboat’s ‘Ole Man River (1927) eloquently explains the burdens of Joe, the weary African American deckhand who knows all too well the narrow boundaries of his life. The song structure written by Jerome Kern heightens its power even more.

The unadorned voice is sometimes a limited instrument. Music has a way of augmenting feelings that can energize an idea. Hammerstein’s You’ve Got to Be Taught from South Pacific (1949) was in its own way a more effective tract against racism than the more discursive efforts of reformers spoken in set speeches. The transformation of a statement conscience into an effective anthem is a powerful thing.

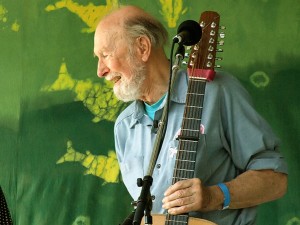

The power of worthy thoughts carried higher of the right melodic and rhythmic structure became clearer to many of us this year with the death of the singer and activist, Pete Seeger. He was 94. The writer of If I had a Hammer and Where Have all the Flowers Gone? was our contemporary Whitman, somehow finding the right sonic forms to gently challenge the nation’s drift away from its core ideals. That he became the musical consciousness of social progressives while also publishing guidebooks on how to play the American banjo somehow completed the circle.

A day after his death on January 27 many of us who followed his career found a copy of one of his tunes attached to an e-mail copy of his obituary. Provided free to the public by his friend Paul Winter, To My Old Brown Earth was actually written by Seeger in 1958, after the death of a friend. But for all of us with the awareness that we would someday lose this beloved man, the song was the perfect eulogy for Pete himself.

The words on the page are graceful:

To my old brown earth

And to my old blue sky

I’ll now give these last few molecules

of “I”

But when sung by the man who was clearly feeling the burdens of his many years, the simple words on the page seem to transmute into a something more elevated and universal. The simple wish of the song to “Guard” “the human chain” is somehow remade into a more durable testament to the living legend we were not prepared to lose. When a chorus finally picks up the theme, the effect is both poignant and heartbreaking.