Few would probably want to listen to a full requiem as their last act, nor would they want to put their mourners through the extended storms of sound that most contain. What works?

One wag once offered the view that death was God’s way of telling you to slow down. It’s probably a better joke only for people who have lived a full and busy life. Yet it is an interesting thought experiment to inquire about the kind of music that might be requested from a person about to depart this world. What might they want to hear, if anything? What might we suggest?

So much music is written to acknowledge death, or to celebrate a person’s life. Brahms, Verdi, Beethoven, Mozart, Haydn, Fauré, and others have written full requiems, or music intended to memorialize the dead. It’s perhaps the least they could do for their mostly private benefactors. The rest of us—if we have such wishes at all—might muse about something closer to home: a piece of music that serves as a kind of summarizing farewell.

This query has some interesting science behind it. We have evidence that hearing is durable to the very end of life, and maybe even a little further. It is one of the last functions to shut down. Even in dying patients, the brain apparently continues to receive sounds through the auditory nerve.

In the film The Big Chill college friends reunite at the funeral of one of the group who took his life in his 30s. Another helpfully pounds out a version of the Rolling Stones “You Don’t Always Get What You Want” on the church organ. The knowing smiles of the rest suggests a building middle-aged angst that director Lawrence Kasdan used as the film’s theme.

Music as the Embodiment of a Life

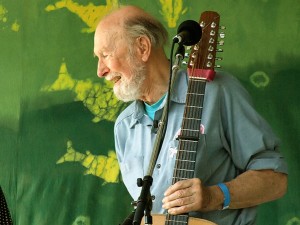

More optimistically, folk legend Pete Seeger seemed to know exactly what he wanted to say in a piece he wrote for a deceased friend. It is a simple ballad that also represents the grace of Seeger himself. The musical tribute he and a choir offer seems just right: a suitable requiem for the Hudson Valley troubadour who died in 2014.

More optimistically, folk legend Pete Seeger seemed to know exactly what he wanted to say in a piece he wrote for a deceased friend. It is a simple ballad that also represents the grace of Seeger himself. The musical tribute he and a choir offer seems just right: a suitable requiem for the Hudson Valley troubadour who died in 2014.

Few would probably want to listen to a full requiem as their last act. One exception might be Gabriel Fauré’s Requiem. The last portion, In Paradisum, is the essence of a musical promise of something better that is yet to come. It is the sonic equivalent of weightless levitation; anyone should feel renewed by its invitation to let the woes of the world to fall away.

There’s clearly no single right choice for all. My regret about those reaching the natural end of a full life is that health care in this period usually won’t allow a last musical denouement. The sounds of hospitals and medical machinery often dominate. Helpful though they are, they often preclude the sonics of what could be a “good death.”

Though I don’t plan to need it soon, right now I’d select the Sussex Carol by the Choir of Women and Girls of England’s Canterbury Cathedral for sustained listening. Young voices put to the service of familiar music can make magic. Next week the choice will probably be something else.

Folks creating films, dramas and operas often find the right mix of musical elements. Composers have to be good at finding musical benedictions that pull off the miraculous task of converting feelings into sound.

![]()