The usual vocabulary of public memorials includes the use height and solidity to reflect rebirth and remembrance. In two of the nation’s most visited monuments that has changed.

Because they are spatial and visual, public memorials exist as walk-through “texts,” giving form to the nation’s preferred narratives of shared loss or defiant restoration. Or so one would expect with the most visited site in New York, the 9/11 Memorial Park created on the site of the original twin towers.

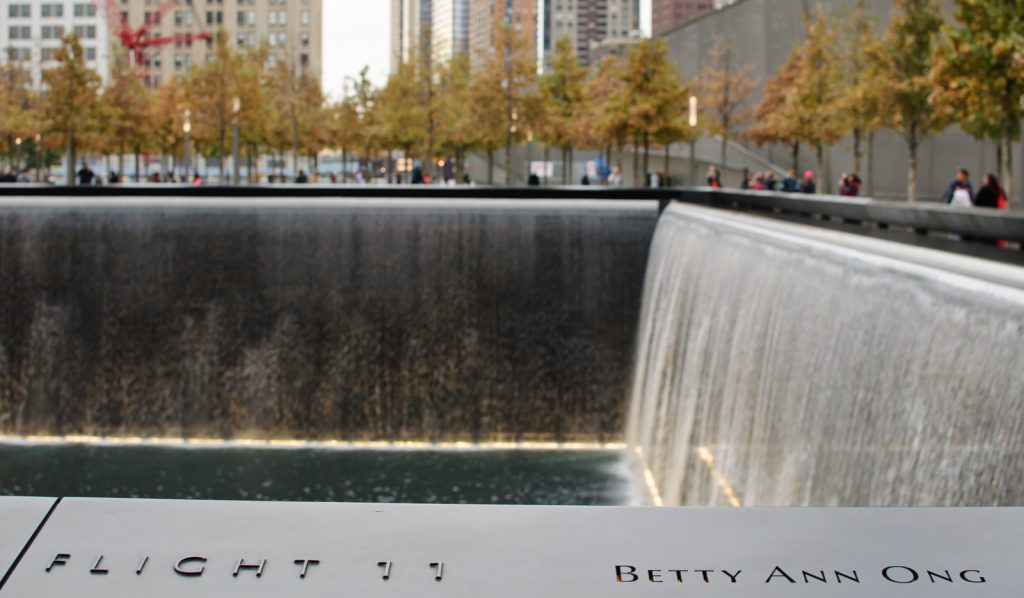

The park in the dense downtown area covers sixteen acres and consists of rows of Swamp White Oaks bridging two massive black cataracts 30-feet deep. These pools are the exact footprints of the two original towers that used to dominate the lower Manhattan skyline. Each wall in these open depressions is softened by waterfalls that descend in a rush to their sub-grade floors. The water then flows into another square opening at the center, dropping to a deeper level that cannot be seen by a viewer at the edge. The idea of total destruction is thus restated, bringing a visitor back to the awful moments when fire and gravity claimed these spaces.

The pools are framed at the top by waist-high bronze borders naming every victim who died in and around the towers, as well as at the Pentagon and on board the commandeered airliner that crashed in Western Pennsylvania. In all, over 3000 victims and rescuers died on that awful day, paying the price of coordinated attacks of terrorists who had turned four commercial aircraft into weapons.

The park is next to a new glass tower, David Child’s somewhat defensive looking One World Trade Center, rising from a ground-level bunker concealed by glass and topping out at 104 floors. The building is clearly meant to be the national answer to the attacks.

Other structures replacing older offices that were also destroyed will soon complete the rebuilding of the site, which includes an underground 9/11 museum.

For the designers, the key imperative was to visually accommodate a jumble of wounded emotions associated with the violation of our national invincibility, while also building a memorial to the men and women who lost their lives. In addition, there was the competing need of the city and the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey to project themselves as still at the vibrant heart of the nation’s financial center. The assault on the city could not be seen as fatal to its future.

All of these sensitivities are at play in the new World Trade Center. Memories aroused on any visit can give way to a host of feelings: pride in the courage of the rescuers on that day, a renewed sense of horror for the suffering of the victims, ambivalence about the root causes of terrorism targeting Americans, and even recent frustrations over whether the nation has been well served by the banking industries headquartered in the neighborhood.

The usual vocabulary of memorials includes the use of height and visual dominance to represent remembrance and renewal. Look at the war memorials in most town centers and they are often shafts of stone rising from sturdy plinths. References to the fallen are usually inscribed on the shaft. In small towns, every soldier lost to the commemorated war is almost always named.

The pools are thus an anomaly. They are empty dark spaces with water falling to their distant basements. They seem to exist to memorialize and metaphorically recreate the disaster, without an ambitious compensating gesture of rebirth. Perhaps this view underestimates the importance of the new tower and the forest of oaks, which have been given ample ground at the site to grow and expand. All are reminders that “reading” any monument to a national trauma can be tricky.

The black pools of lower Manhattan join the black stone trench of the Vietnam Veterans Memorial at the western end of the Mall in Washington D. C. It carries the names of over 58,000 soldiers who died in the long war that tore the nation apart in 1968. Maya Lin’s design was initially disparaged as a “gash of shame” because the memorial recedes into the ground rather than rising above it. But even with these initial doubts, the site has become a potent emblem of the sacrifices of that war, with aging vets always around and eager to bear witness to those whose names are etched in the black granite.

A visit to the wall is like a trip to a cemetery. The nearby Jefferson, Lincoln and Washington Monuments are more effusive; it’s easier to glorify a person than a long “quagmire” that turned into a losing cause. The Vietnam memorial can be read as a national acknowledgment of the enormous human costs of a tragic misadventure.

Taken together, it’s easy to see these vital monuments as representations of a more subdued national character. National politicians continue to preach the political equivalents of Old Testament dominance and retribution. Faith in American exceptionalism is still woven into their rhetoric. But these newer monuments tell a very different story.

Comments Woodward@tcnj.edu