Political iconography is always interesting to read for attitudes and assumptions that are displayed rather than articulated. Visual imagery easily cuts through the limits of an individual’s level of fluency: their reluctance to “own” explicit language or express taboo thoughts. What people want to display can function as substitutes: visual analogues of fantasies and grievances.

Anyone viewing the images carried by the rioters who broke into the Capitol Building on January 6 could not help but notice that they communicated mostly through with flags and posters. Few seemed to be ready to address issues relevant to the deliberative space they occupied. And few pamphlets or tracts were left in the ransacked sections of the building: mostly flags that seemed to owe as much to shooter games and action films as any thought-out ideology. Such is the impoverished language of much of our civic culture that a person with poor eyesight could be forgiven for momentarily thinking the aggrieved monsters were just a disorderly drum and flag unit. But we now known their deadly intent.

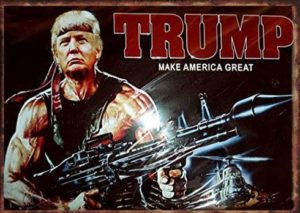

The image above of a “Rambo Trump” was on a flag of one of the insurrectionists staging the assault. It’s both funny and sad: comic book muscles, a lethal weapon, a look of toughness, a male color palette: all seemed to speak for some of those present and now charged with assorted crimes.

The flag can be purchased from an online dealer, and certainly invites a range of reactions to its intention to inspire: absurd, juvenile, pathetic, the detritus of a mind degraded by digital games. What could the carrier of the image have been thinking? Could he put his unintended cartoon into words? And how does someone end up wanting to carrying around an agitprop image of a sedentary and defeated real estate  developer whose rhetorical weapons are schoolyard taunts and a nasty sneer?

developer whose rhetorical weapons are schoolyard taunts and a nasty sneer?

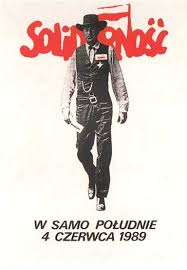

The Rambo image is an echo of the poster image used by Poland’s Solidarity Movement featuring Gary Cooper from the 1952 film High Noon. Cooper’s Will Kane was a peaceful man goaded into a showdown with a crook: a strong but reluctant sheriff who could articulate his principles. Guns were not his preferred tools of persuasion. And Cooper, who convincingly played a Quaker in Friendly Persuasion, could pull it off. In short, Solidarity in the 1980s was saying, among other things, that character mattered, that there is nobility in a degree of quiet dignity.

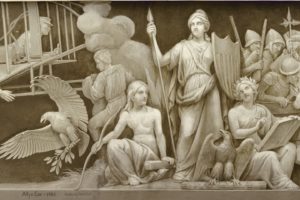

What a difference with the mob looking for someone to attack in the Rotunda, all under the gaze of the landmark paintings of John Trumbull, and the striking frieze by Constantino Brumidi just above them. To be sure, Brumidi’s images of moments in the national’s past are their own kind of preferred narratives that are now out of step with more recent revisions of the historical record. Even so, the Rotunda was completed as Lincoln’s message that the union had a future. It was to be a visual plea for unity and a dramatic way to honor the nation’s history. It’s doubtful those breaking into the Capitol had a clue about the hallowed ground they occupied, or how to engage others in ways appropriate to it.

What a difference with the mob looking for someone to attack in the Rotunda, all under the gaze of the landmark paintings of John Trumbull, and the striking frieze by Constantino Brumidi just above them. To be sure, Brumidi’s images of moments in the national’s past are their own kind of preferred narratives that are now out of step with more recent revisions of the historical record. Even so, the Rotunda was completed as Lincoln’s message that the union had a future. It was to be a visual plea for unity and a dramatic way to honor the nation’s history. It’s doubtful those breaking into the Capitol had a clue about the hallowed ground they occupied, or how to engage others in ways appropriate to it.

![]()