Friends of singer Tony Bennett noted that his last years with dementia did not deter him from performing his music.

[Music remains unique in its ability to refire memories that have been dormant. Perhaps it is a trigger to important “autobiographical memories.”]

It seems impossible to consider the vital sense of hearing without celebrating the special phenomenon of music, which has a lock on many of us. Watch a two-year-old child move to the beat of a song and we are reminded that the ear readily learns to love music’s embedded rhythms. Often minimized as a pleasant addendum to life, music is more accurately described as central to its enactment. It is undervalued if it is seen as anything less than a prime generative source for refreshing the human spirit.

All of this was eloquently reinforced in Michael Rossato-Bennett’s 2014 documentary, Alive Inside. The filmmaker initially signed on for just one-day to film an effort to reclaim an older American lost to dementia. The experiment soon captivated the filmmaker and became a full-time project.

Most of the film’s subjects were selected by social worker Dan Cohen, who discovered that many seniors reconnected with their own lost memories when reintroduced to the music of their youth via a compact player. For one older gentleman it was simply enough to hear the restless swing of Cab Calloway through earbuds to lift a fog of non-communication. Beyond kick-starting lost memories, the music brought the man alive emotionally. He suddenly had access to his distant past as an accomplished dancer and musician. It was the “mental glue” that held his old self together.

The idea of a wearer of a set of headphones experiencing private ecstasy is hardly new. But it means so much more when the person listening was thought to be little more than a piece of human furniture. It turns out that music is the perfect vehicle for reclaiming memories thought to be gone forever. Neuroscientists have noted that music triggers well-named “autobiographical memories” that can be tapped in almost no other way. In the words of Australian researchers Amee Baird and William Thompson, music can be “an island of preservation in an otherwise cognitively impaired person.” Songs “powerfully engage the frontal regions of the brain, which are typically spared from damage.” The neural pathways that relay music are among the most durable in the brain. Friends of singer Tony Bennett noted that his last years with dementia did not stop him from coming fully engaged again when asked to sing his music.

The same was true in Rossato-Bennett’s documentary when headphones were placed on Mary Lou Thompson, a younger woman perhaps in her early sixties with early-onset Alzheimer’s Disease. Even recognizing the purpose of an elevator button was difficult. Thompson’s husband could only marvel at the sight of his wife, earbuds in place, slowly unfolding her lean, tall frame to glory in an old Beach Boys song she obviously never forgot. It was like watching a time-lapse image of a closed flower opening to the sun. I’ve seen very few screen documentaries that so dramatically revealed a person’s instant transformation.

There may be reasons to lament the mobile phone as a device that undercuts the value of direct and immediate experience. But there can be no doubt that a portable music player enriches us by being a potent memory trigger.

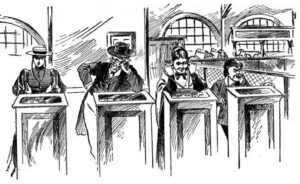

Even the crusty innovator Thomas Edison sensed music’s power to mesmerize. Listeners at the 1893 Columbian Exhibition in Chicago clamored to hear distant voices and songs on his audio cylinders, often through rubber ear tubes. It was then a miraculous idea that voices could be captured in midair to be heard years later. Even though he had become deaf, Edison seemed to understand the regenerative possibilities of sound for rebuilding the human spirit. It’s no surprise he identified the humble phonograph as his most satisfying invention.

Even the crusty innovator Thomas Edison sensed music’s power to mesmerize. Listeners at the 1893 Columbian Exhibition in Chicago clamored to hear distant voices and songs on his audio cylinders, often through rubber ear tubes. It was then a miraculous idea that voices could be captured in midair to be heard years later. Even though he had become deaf, Edison seemed to understand the regenerative possibilities of sound for rebuilding the human spirit. It’s no surprise he identified the humble phonograph as his most satisfying invention.

![]()