When you find yourself reminding a friend of what you told them yesterday, you are in the familiar territory of recalling something that mattered more to you than them.

Occasionally an idea in communication comes along that provokes the realization that it would not be possible to live without it. Good models can help us see what is right in front of us. So it is with a set of observations that fall under the name of Elaboration-Likelihood Model. The name might be a little off-putting. But as a framework for insights about how messages are likely to be received by others, the model is golden.

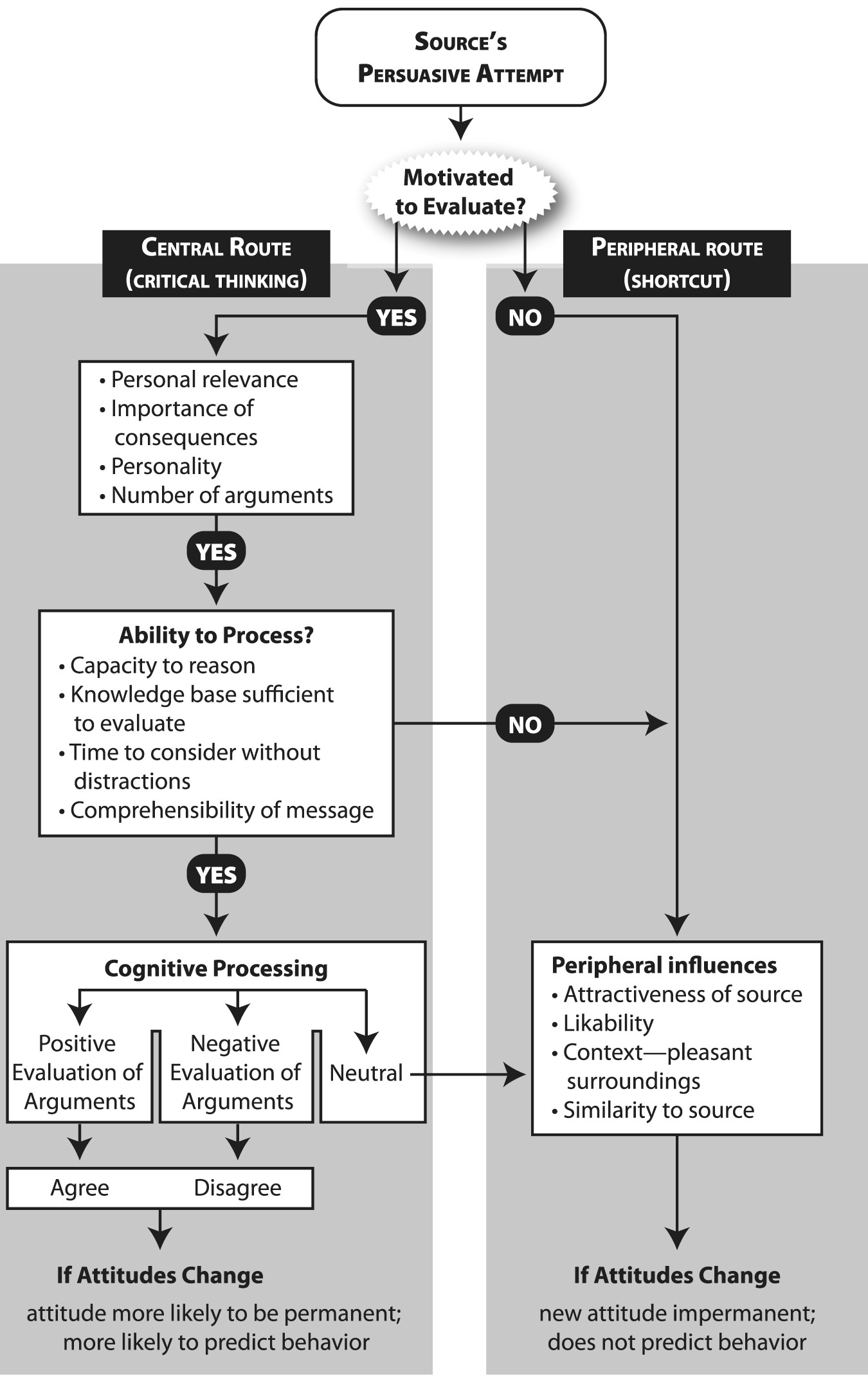

The work of Richard E. Petty and John Cacioppo, the model proposes that we think about the reception of messages as coming via one of two general pathways. Messages that are “centrally processed” are, by definition, the kinds that trigger a whole set of critical responses. These are claims and ideas readers or listeners think about. Their engagement means that they are more inclined to test these assertions against what they know. Their beliefs or behaviors have been put in play and may change.

The model assumes that serious attempts at advocacy or involvement must gain a strong foothold in our consciousness. Those that don’t—those messages that get scant attention—are said to be “peripherally processed.” A message like an advertisement or a casual request from another may wash over us quickly. We are not especially interested or motivated to hang on every word. And, as you would guess, the message is not likely to produce significant or lasting change. It has not created an impression that sticks.

All of this may seem more or less obvious. But considering how much a person or audience cares is a worthwhile question. It asks if you can trigger enough attention and interest to have a chance at getting change. As labels, “Peripheral” and “Central Processing” are good ‘top-of-mind’ concepts.

The model’s relevance increases every year as Americans recede into ever-deeper waters of message overload. We simply weren’t made to attend to what is now a routine exposure to many hundreds of messages every day. We may deceive ourselves into believing that we can multi-task and accurately consume all that it thrown at us. We can’t. Truth to be told, we’re not good multitaskers. Peripheral processing means that we will miss too much to feel bound by a specific request.

Watch a skilled grade school teacher handle a class and you will see a survivor who knows that active listening and central processing are essential and hard won. It takes time, repeated attempts, a lot of eye contact and follow up. When we get older we are our own bad actors, staring at phones, drifting into other thoughts and ideas, and distracted by internal chatter that will not allow us to focus.

Another person’s attention is essential. But it can’t be easily given.

When you find yourself saying to a friend our spouse “I mentioned it yesterday; I’m sure I said it” we are likely recalling something that mattered much more to us than the person who was supposed to be listening. And, while we can get frustrated at the other’s inattention, we also need to cut them the slack by recognizing that communicating with a peripheral processor is a bit like shouting in the forest. The people close by may look like they have heard us. The Elaboration Likelihood model reminds us to have some doubts.

Consider two recommendations. Repeat what you deem important. A tactful rewording of the message that you want to stick may help get the reaction you want. In addition, give the peripheral-processing “forgetter” some slack. To attend to every message that comes to us is not possible. If you tried to do it, you would need a mental health intervention. To be sure, another person’s attention may be expected. But the the requirements for sanity in an over-communicated society mean that it can’t be easily given.