By necessity, A.I. must assume a kind of fraudulent authorship, easily revealed in meaningless pronouns.

The recent flurry of news about refined A.I. “intelligence” which can process and mimic coherent discourse– if not authentic emotional states—has been hard to miss. But in the breathless rush to proclaim the human-like capabilities of ChatGPT and other language-based systems, something basic has been overlooked. The real deficits of these programs are their incapacities to handle human processes represented in meaningful pronouns.

Obviously, these systems are using language and grammar forms we recognize, but their shortcomings are concealed by their verbosity. We now have chatbots that can talk more than our worst oversharing relatives.

Here’s what’s missing. When we use it, the pronoun “I” is the human equivalent of the North Star. Our awareness of it gives us the power to take ownership of objects, needs, feelings, and a reserved space in what is usually a growing social network. Children learn this early, building an emerging sense of self that expands rapidly in the first few years. Eventually they will distinguish the meanings of other pronouns that allow for the possibility of not just “I,” but “we, “you,” and “them” as well. This added capacity is a major threshold. It’s an immense task to fathom other “selves” with their distinct social orbits and prerogatives. Adequate consideration of another’s “otherness” is a lifelong process that even adult humans struggle to master. As examples of this capacity importance, consider the elaborate backstories of motivation that you routinely apply when talking to a friend or family member. What is heard and what is understood may be two very different things. Understanding others is a delicate process of inference-making that can’t be duplicated by a machine that lacks a requisite social and organic lineage.

This shift to “I” from “we” also enables us to assert intellectual and social kinship, one biological creature to another, bound by an awareness of similar arcs that include learning, living and dying. These natural processes motivate us to assert our own sense of agency: to be engines of action and reaction. We “know” and often boldly announce our intentions, at the same time doing our best to infer them in others. Estimations of motive shape most of our conversations with others. Think of the “I” statements used by others as sitting atop a deep well of attitudes and feelings we struggle to bring to the surface.

So, it is clear that every time Chat GPT composes a message to us, it needs to depend on fraudulent pronouns, stated or implied. It uses forms of everyday language that conceal the fact that it has no resources of the self: no capability to “feel” as a sentient being. This makes it clueless in gaining even a rudimentary sense of what others are about.

![]()

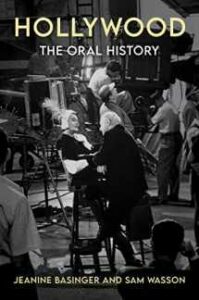

Basinger and Wasson work to correct the common impression that it is simply stars and directors who make screen magic. At least the book starts in that frame of mind, until later sections succumb to long passages from directors and producers who have some scores to settle with actors and studio heads.

Basinger and Wasson work to correct the common impression that it is simply stars and directors who make screen magic. At least the book starts in that frame of mind, until later sections succumb to long passages from directors and producers who have some scores to settle with actors and studio heads. turn Tom Hanks into Elvis’s manager, “Colonial” Tom Parker for the 2022 film, Elvis. Similarly, making effective use of light in specific scenes is its own art. Years of watching a colleague teach film lighting made it clear that it is possible to turn film into a convincing three dimensional medium. Official recognition usually goes to the Director of Photography. But unnamed scene or lighting designers may have added just the right magic.

turn Tom Hanks into Elvis’s manager, “Colonial” Tom Parker for the 2022 film, Elvis. Similarly, making effective use of light in specific scenes is its own art. Years of watching a colleague teach film lighting made it clear that it is possible to turn film into a convincing three dimensional medium. Official recognition usually goes to the Director of Photography. But unnamed scene or lighting designers may have added just the right magic.