The best parts of this 700-page volume come early, with observations from people working in often-ignored theater crafts that make the talent look good.

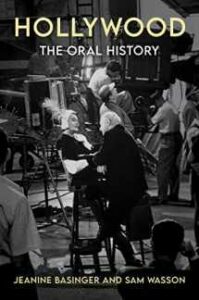

A new book, Hollywood: The Oral History (Harper, 2022), is compendium of hundreds of interviews with film industry figures–familiar and unfamiliar–more or less organized by topic. It is indeed an oral history, because these folks recorded their thoughts in conversations archived by The American Film Institute. Nearly 400 industry people are quoted in various parts of the book. Many are no longer with us, but academics Jeanine Basinger and Sam Wasson have put together a panoramic range of interviews that offer compelling details about filmmaking, including the years before sound. Producers, directors, crafts people and actors offer candid memories of their work under the old studio system, or the newer one-off pattern of film production that has replaced it. Posterity is the beneficiary here, with more than a few people anxious to correct the record offered by studio publicists or on display in the final credits.

Basinger and Wasson work to correct the common impression that it is simply stars and directors who make screen magic. At least the book starts in that frame of mind, until later sections succumb to long passages from directors and producers who have some scores to settle with actors and studio heads.

Basinger and Wasson work to correct the common impression that it is simply stars and directors who make screen magic. At least the book starts in that frame of mind, until later sections succumb to long passages from directors and producers who have some scores to settle with actors and studio heads.

The best sections of the 700-page volume chronicle the memories of “the studio workforce” including the people working in the too-often neglected theatrical crafts that make talent in front of the camera look good. Amazing talents doing the work of costuming, set design, makeup, photography, and music all chronicle some of their efforts on various projects, reminding us of just how collaborative filmmaking is. This redirection of attention is important because our endless attention on actors us obscures the sometimes brilliant visual and audio details that give films their memorable attributes.

As examples, costuming, makeup and lighting require great amounts of time and convincing invention. But these folks mostly labor in obscurity. One costumer notes that Edith Head at Paramount got scores of Oscars, some for clothes that others in her department actually designed. Credit is also due to whoever was able to turn Tom Hanks into Elvis’s manager, “Colonial” Tom Parker for the 2022 film, Elvis. Similarly, making effective use of light in specific scenes is its own art. Years of watching a colleague teach film lighting made it clear that it is possible to turn film into a convincing three dimensional medium. Official recognition usually goes to the Director of Photography. But unnamed scene or lighting designers may have added just the right magic.

turn Tom Hanks into Elvis’s manager, “Colonial” Tom Parker for the 2022 film, Elvis. Similarly, making effective use of light in specific scenes is its own art. Years of watching a colleague teach film lighting made it clear that it is possible to turn film into a convincing three dimensional medium. Official recognition usually goes to the Director of Photography. But unnamed scene or lighting designers may have added just the right magic.

In the recent past these amazing talents have gotten insufficient recognition from the Motion Picture Academy, which builds the all-important Oscar ceremonies more around directors and the talent dressed for a fashion show. Production and post-production people who make it all work—directors of photography, film editors, Foley artists, music arrangers, set designers, and others—have gone barely recognized in the yearly television spectacle. Giving their awards at an earlier ceremony or during commercial breaks are bad habits that this year’s planners say they intend to correct. Imagine your own organization’s faux version of the Oscars–and there are many– where only the prettiest people receive most of the attention.

Basinger and Wasson use most of the book’s space quoting the impressions of stars, directors and producers. Much of the talk is about co-workers who were good collaborators, and some who were not. Among others, the tragically overworked Judy Garland gets a noticeably rough ride here. But I would have liked to have read more about the challenges of a cinematographer facing the task of lighting a particular scene, or the solutions developed by a sound editor to salvage dialogue that can’t be “looped” in post- production.

There’s an old saying that all of us have two vocations: our own fields of work, and as witnesses to the many worlds of the entertainment business. So it makes sense that we should want to be smarter about how the narratives we love or hate came to be.

![]()