There is a wide perception that it is the moderator’s job is to comment on lies, half truths or false claims. But that’s the job of the other debater. In a good debate the participants aren’t answering reporter’s questions, but fact-checking each other.

The political season always brings out a cycle of “debates” finally agreed to by cautious candidates, news organizations, and good government groups. Though everyone involved has different motives, the one most commonly expressed is that debates offer the public the chance to compare candidates side by side. In the unfettered give-and-take of a debate we are supposed to learn about issues that divide and sometimes unify those running for the same office.

And yet most of these joint appearances are a sham. As usually formatted, they can’t achieve the lofty goals they allege.

A public debate done correctly should deliver what philosophers call “dialectic:” a purposeful clash of views where claims and evidence are tested against a series of counter-arguments. Among others, Aristotle was certain that acts of public advocacy had a cleansing effect on the body politic. He believed we are wiser for subjecting our ideas to the scrutiny of others. This may sound lofty and abstract, but most of us do a form of this when we talk through a pending and important decision. We often want friends to help us see potential problems to our proposed course of action.

In open societies such as ours we expect to hear the contrasting opinions. It’s a wonderful process when it can be properly formatted. Otherwise—and as devised by most political operatives—a political debate is usually is little more than a joint press conference.

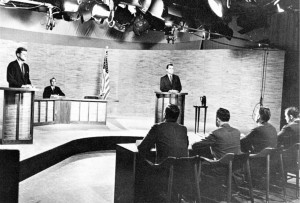

The problem is that candidates usually fear these exchanges. They and their staffs believe that a serious gaff can sink an entire campaign. So they hedge their bets. They agree to “debates” if they are moderated by a panel or at least a single journalist. This is when the process begins to go south. It’s further doomed when each side is given only a minute or two to respond the statements of opposing candidates. These errors are then compounded with a final counter-response that is barely the length of a sneeze. As it now exists, it’s little more than a lukewarm form of political theater.

I especially regret that the national Commission on Presidential Debates that includes some of my professional colleagues hasn’t significantly altered this ersatz format. A true debate will have no more than a moderator or time-keeper to equalize participation and keep things civil. In true debates there are no outside questioners. The advocates directly address the claims and arguments of their opposites on what is usually a single broad but important subject area. Their opening remarks must be permitted to be longer than a television commercial. They listen, refute, question, and challenge each other. When one issue seems to have been exhausted, the moderator may steer the pair to a related issue and then get out of the way.

Lincoln and Douglas debated for hours by themselves without the assistance of others. Indeed, a prime form of Saturday night entertainment in the 19th Century was a formal debate in a town’s biggest venue. The whole process of seeing two leaders explain their ideas under the scrutiny of an interested audience could be invigorating. By contrast, the short question-based formats commonly in American political debates generally ruin the chance to see how much a candidate truly knows beyond the memorized sound bites that they repeat at every stop. Just when follow-up rebuttals might begin to test a candidate’s knowledge of an issue, the questioners usually interrupt and move on to a new topic.

Last year Americans could catch a series of BBC debates in the United Kingdom between Alistair Darling and Alex Salmond on Scotland’s referendum to go it alone as an independent state. These weren’t perfect by any means. But these televised clashes had the advantage of allowing both sides sufficient time to make essential arguments and extended refutations. As can be seen during weekly Prime Minister’s Questions in the House of Commons (available on C-SPAN’s website), the British expect that their leaders should be able to stand up under sometimes withering criticism from their ideological opponents.

Our system conspires to do the reverse by giving unnecessary screen time to outside questioners, thereby protecting candidates by allowing them to stay in a comfort zone of stump-speech clichés and bumper sticker retorts. Debates should expose the relevant facts and hard truths behind a decision to support or oppose an action. We never let the candidates go on long enough to see if they have confronted those truths.