A person with high social intelligence has a set of ‘antennae’ that can be a guide for behavior that will give another more comfort than pain.

We are used to thinking of “intelligence” as a single entity. But it’s not so simple. To be sure, we have IQ scores and other measures of a person’s capacity for understanding abstract ideas and processing information. But traditional measures of intelligence are notoriously imprecise. The term itself is difficult to operationalize, something that must happen with “objective” and comparative measures. It’s thus problematic to saddle an individual with a number that is supposed to stand as a representation of their cognitive skills. It’s not unlike establishing the overall worth of a car by the time it takes it to go from 0 to 60 mph. You can do it, but it misses a lot. By contrast, there is something of greater value in the idea of social intelligence, even though it also will not easily yield to the insistence in most of the social sciences for specific metrics.

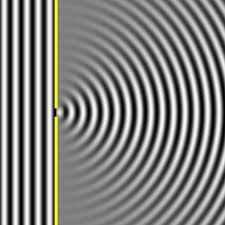

Broadly speaking, social intelligence is a capacity to “read” others and make adjustments to meet their expectations and norms. In practical terms, this turns out to be mostly a function of a person’s skill in knowing how to use a familiar ‘script’ employed in a given setting. Opening a door for someone with a heavy load or asking the perfunctory “How are you?” are common scripted behaviors.

Psychologists sometimes talk about ‘theory of mind” as the related capacity to be able to anticipate what is going on in another person’s life, making adjustments that are more empathetic than indifferent. We know it when we see it, as when another person has said what seems like just the right thing to a needy friend. We have also walked away from a conversation suddenly realizing that we wadded into a topic they consider taboo.

In actual fact, there are assorted ways we can sense another person’s social intelligence: in their abilities to self-monitor impulses that might be awkward, in a general willingness to engage even with strangers, or generally knowing how to listen to another and make appropriate responses. A person with high social intelligence could be said to have a set of ‘social antennae’ that are strong enough to grasp what will give more comfort than pain to another.

The phrase “social intelligence” is perhaps most clearly associated with the psychologist, Daniel Goleman, and his best-selling book under the same name (Bantam, 2006). The book is a worthwhile study, even if its subtitle oversells the subject as a “science of human relationships.”

My own favorite thinker in this area is the less flamboyant sociologist, Erving Goffman. In his ever-popular Presentation of Self in Everyday Life (1959) he notes that we are actors creating responses appropriate to a given scene. I don’t believe he ever used the phrase, but he was dogged in reminding us that social relationships are predicated on functional presentational skills. He talked about “impression management” and role taking as capacities that lie at the core of our relational world. His mode of explanation was based less in survey research, using instead a method of deep description, giving simple exchanges a careful ‘reading’ of what they mean and reveal.

When observers see Donald Trump’s behavior as sometimes “unpresidential,” they are doing a kind of dramatic critique.

The shift in perspective makes a big difference. Social intelligence is best understood as a function of our ability to perform words and deeds that are a good match for a given situation. There is no single standard or set of norms, effects or skills, but infinite possibilities.

This is why the dominant art form in our lives is film, with all of its variations and platforms. Seeing individuals act in the presence of others is always a potential touchstone. Comedy generally lets us see people behaving badly, or at least inappropriately. Our laughter flows from a recognition of violated social codes. And drama puts us in close to see moments when lives can be transformed. It isn’t the transformation itself that grabs us. It’s a character’s response to the problem that precipitated it. Their reactions are how we come to know the features of their character, especially their aptitude for rising to meet social circumstances fraught with complexities.

In a sense we are all critics of performances, using personal preferences and floating standards to assess the responses of others. This more open-ended dramatic framework gives us the kind of pluralism of potential responses we need to understand the marvels and occasional disasters that unfold in social encounters. For example, when observers see Donald Trump’s acts as sometimes “unpresidential,” they are doing a kind of dramatic critique. However smart he is or isn’t, he is mostly graceless around others. People have favorite examples. One of mine: refusing to shake hands with Germany’s Angela Merkel during a White House photo-op early in his administration.

A final thought: It’s not unreasonable to expect a challenge to the Goffman view of social dramas on the grounds that digital media that was not around in his day takes us out of public spaces. We obviously communicate much more via devices, and often with complete anonymity. In these media we hardly pay attention to polite rules of engagement. Our statements can be all of “us” with little worry about “them.” Current research suggests this may be happening with our youth, who seem to struggle more to willingly meet adults and strangers face to face. The nominal discomfort most of us felt growing into the adult world has lately grown to levels in the young that approach paralyzing fear.

I suspect that’s our problem more than it was his. Social norms may change, but the need to match our behavior to them does not.

![]()