Rogers assumes that all of us have music “sweet spots” that come from causes that can’t be fully explained

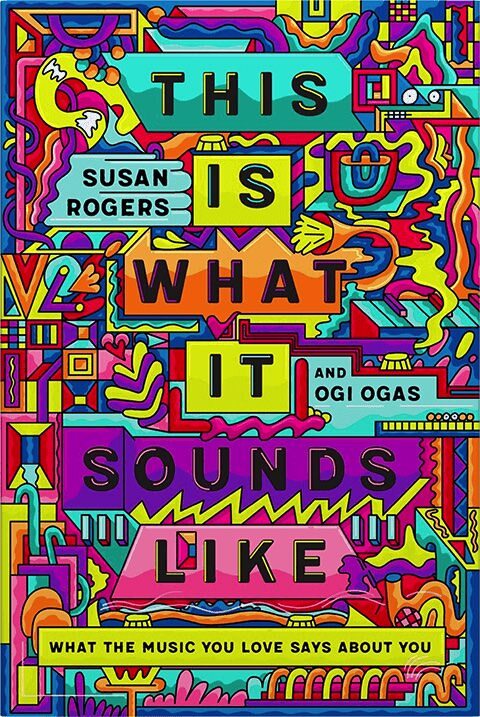

A book published this year by record producer Susan Rogers raises one of the great conundrums when writing about the arts. Her book, This is What it Sounds Like (co-authored with Ogi Ogas and published by Norton) is a valiant attempt to assess what it is we love and we hear a favorite piece of music. What, exactly, is going on? It can be hard to wade into these dark waters that conceal unseen holes that can pull a writer way out of their depth. As one critic put it, when writing about popular culture it’s hard to not sound like a jerk.” But Rogers has produced albums for Prince and a host of other bands and singer/songwriters. In addition, she regularly takes the pulse of modern listeners as an instructor of Record Production at Berklee College of Music. She’s a professional listener at a school that has a reputation for helping students who want to get foothold in the mysterious commercial music business.

In the book we learn that she and her co-author share very few of the same musical passions. Her tastes run to grunge rock, for example: preferring the rougher style of the Rolling Stones to the more polished playing and production that was common with the Beatles. But she also acts on the premise that there is little point in pressing one’s case that a certain song or album is superior to another. She wants to build an understanding of why we have such different tastes, without dwelling on the weaknesses of individual talents. That’s what music critics do, and sometimes very well. But music is a phenomenological experience. Studies of neural mechanisms of hearing will only get you so far. That’s as it should be, but I can attest to the fact that it makes life difficult for academics if they venture beyond the safe tropes of the social sciences.

So, challenges to write sensibly and clearly about popular music are enormous. Music is its own language. A writer must translate feelings and the attributes of specific sonics into verbal forms that range from barely adequate to very clumsy. Needless to say, analogies abound: everything from discussions of auditory “circuitry” to “whispers” of sound, and even to tactile terms like “harsh” and “cold.” Sometimes these conversions work, and at other times they surely distract us from the difficult task of communicating more nuanced features of music. If you assume that a composition is wonderful because it exceeds what can be explained in ordinary language, then it is easy to see how the whole enterprise of musical dissection can be a fool’s errand. But Rogers is aware of this problem. At many points in her book she is candid enough to admit that nothing can replace the experience of listening to a specific effort.

Rogers assumes that all of us have music “sweet spots” that come from causes that can’t be fully explained. We may have a preference over, say, acoustic rather than electronic sounds, syncopation over straight rhythms, broad melodies in lieu of more obscure ones, and so on. She rightly assumes that there’s no sense in trying to find a neurological reason to prefer one attribute over another. For example, some of us get hooked on a particular timbre, never able to hear enough of the kind of sound produced by an instrument or singer. The sonics of any piece always have their own unique features. And for true “sound centrics,” hearing particular timbres is reason enough to go back to the source again and again. The organ-like tones coming from a steel band work for me. Others of us prefer the distortion or the “on the beat” music of a rock song with the out-front thud of bass coming from a drum machine locked into the same tempo.

Throughout the book Rogers takes the musicianship of those she works with seriously, noting at one point that even the best often have to hold back to make a particular tune fit with the rest of a band. In our era, and for most listeners and record producers focused on pop music, virtuoso playing is hardly the point.

I can’t say that I have spent much time with the kinds of music Rogers likes to record. But I admire he ability to maintain a panoramic view of music. And it is indeed helpful to try to identify some musical “sweet spots” that make listeners swoon and a handful of musicians unexpectedly rich.

![]()