A reasonable noise level at a restaurant should be about 65 decibels. But many can top 85. Little wonder noise is the most common complaint about eateries of all sorts.

These days when the New York Times restaurant critic Pete Wells writes reviews, it’s not uncommon to read about sound levels in expensive establishments that are “abusive” or “overpowering.” That’s not always the case. But high New York rents dictate small rooms with many tables. And the bar culture especially in after-work watering holes nearly duplicates the sound intensity of the beachside runway on St. Maarten’s. We have all had the experience of spending an evening with others where our time together was defined less by the food coming from the kitchen than our skill as lip-readers.

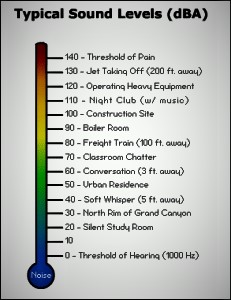

The World Health Organization notes that the normal nighttime noise level for a large city should be no more than 40 decibels. (This measurement scale is logarithmic; every three decibel increase roughly doubles perceived sound intensity.) Continuous sound topping 55 decibels can leave a person at risk of cardiovascular disease. That’s a considerable distance from the 120 decibels that can produce permanent hearing loss: a real risk for musicians of all sorts.

The World Health Organization notes that the normal nighttime noise level for a large city should be no more than 40 decibels. (This measurement scale is logarithmic; every three decibel increase roughly doubles perceived sound intensity.) Continuous sound topping 55 decibels can leave a person at risk of cardiovascular disease. That’s a considerable distance from the 120 decibels that can produce permanent hearing loss: a real risk for musicians of all sorts.

A reasonable noise level for a busy restaurant should be about 65 decibels. But many restaurants easily top 85 in their bars and main dining areas, a fact aggravated by the tendency of well lubricated patrons to talk even louder. Maybe the hard stuff should come with a noise warning as well as a warning to drink in moderation. Little wonder noise is the single biggest complaint leveled against eateries of all sorts.

Many eateries are also designed to reflect rather than soften noise. And nothing is a greater problem than hard surfaces, especially glass. Glass harshly reflects sound back on us, even while it seems visually transparent. So even a table with a beautiful view may be no better than sitting in a three sided box. In practical terms, avoid the offer of a seemingly cozy booth with a view that is also just a few steps from the bar. If the place is busy, you are likely in for a sound circus. As I documented in The Sonic Imperative: Sound in the Age of Screens, all of that alcohol-fueled reverie a few feet away is going to come you way twice: once as the sound travels to the window, and then again when it comes back to your ears a few microseconds later.

Many eateries are also designed to reflect rather than soften noise. And nothing is a greater problem than hard surfaces, especially glass. Glass harshly reflects sound back on us, even while it seems visually transparent. So even a table with a beautiful view may be no better than sitting in a three sided box. In practical terms, avoid the offer of a seemingly cozy booth with a view that is also just a few steps from the bar. If the place is busy, you are likely in for a sound circus. As I documented in The Sonic Imperative: Sound in the Age of Screens, all of that alcohol-fueled reverie a few feet away is going to come you way twice: once as the sound travels to the window, and then again when it comes back to your ears a few microseconds later.

The problem is common enough to get a separate web page from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Their recommendations:

- Spare your kids the noise.

- Eat at off times.

- Request that music or the sound on televisions be turned down

- Ask for a quieter corner away from loudspeakers or loud groups.

There is a curious fact about excessive noise. Many of us don’t notice it. We are used to moving through clamorous environments that push at the margins of comfort. Some of us are natural stoics, bearing the burden of too much noise until it is mentioned by others. This is one reason excessive sound volume is a contributor to stress, not to mention permanent hearing loss. As ambient sound turns into a roar it stretches the natural elasticity of our patience. In the end, we feel drained and fatigued without exactly knowing why.

![]()