We use everyday garments to announce our identities in lieu of the more awkward task of trying to explain them.

The Victorian writer Thomas Carlyle was not the first to notice that clothing makes its own rhetorical statements. But he was clear in noting that “coverings” can be material and well as verbal. Just as we sometimes clothe our motives in language that conceals less admirable impulses, so we use everyday garments to announce our identities in lieu of the more awkward task of trying to spell them out. For Carlyle “the first spiritual want of man is decoration.” How we choose to appear before others is perhaps the straightest line to identity. It’s little wonder that teens grappling with an awkward transformation to a more personal self would be so particular about how they appear to each other.

Concerns with clothing and appearance can last for an entire lifetime. As the New York Times notes, no one was really surprised to find an apparently expensive Christian Louboutin stiletto stuck in an escalator near the new editorial offices of Vogue at One World Trade Center. Some well-dressed employee obviously moved on without it. At best, even the most policed architecture in the city can only delay but can’t deter the mavens of high fashion.

The principle of clothing as a “statement” is only more exaggerated in the fashion world. In reality nearly all of us trade in the imagery of personal presentation.

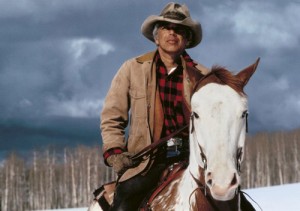

Consider three cases that exemplify the power of selected external skins to announce what we want to believe about ourselves. Designer and fashion mogul Ralph Lauren was born Ralph Lifshitz in the Bronx 75 years ago. Today the Lauren empire often features the short and photogenic President in clothing that has become one of his signature styles: a leather or wool-lined jacket, a western hat that looks like its been kicked around the corral a few times, hand-tooled boots and jeans. Even as a teen in the Colorado mountains I never succeeded in looking so ranch-hand cool.

And there’s the case of the iconic tamer of the West, John Wayne, born Marion Morrison in Winterset Iowa. Wayne apparently disliked horses. But nothing in his past and his Midwestern roots would deter him from becoming Director John Ford’s favorite trailblazer. The Duke achieved on film what Theodore Roosevelt constructed in his larger-than-life legacy. He transformed himself from a sickly son of a Manhattan socialite into the “Rough Rider” who relished the possibilities of taming any country that could test his masculine prowess.

Donald Trump from Queens offers a related case that is more firmly anchored in the urban jungles of America’s biggest cities. Trump grew up into a comfortable family thriving on the business of building modest apartments and single-family homes in the Jamaica Estates area in Queens. He obviously expanded the base of the Fred Trump organization, creating a Manhattan-centered development model more suited to his ambitions as a real estate juggernaut. Though he would have us believe that he is a master-builder, a closer reading of his career suggests an aptitude for real estate marketing and self-promotion. Trump wears aggressive entrepreneurship as a badge of honor.

This mix of material accomplishment and relentless hype can be seen in a soaring Skidmore-designed building along the Chicago River. Its 20-foot tall TRUMP nameplate spanning the 16th and 17th floors is so large that one can imagine the structure listing toward the river under its weight. To be sure, the handsome 98-story structure—officially the Trump International Hotel and Tower–complements the skyline, and–unlike many–was his project from the start. But the outsized sign mars its sleekness and feeds stories among locals of the New York vulgarian who somehow still managed to blow in, even against the stiff prairie winds from the West. The twist is that the gaudy gold and chrome skins of his buildings have become surrogates for the conservative business attire even a brash mogul has to wear. For most of us the need for self-definition permits less flamboyance. But few of us are immune from the urge to calibrate our “look” to match our aspirations.

Comments: woodward@tcnj.edu