If given the chance, the founders of the nation could rightly put the blame for our current disintegration back on us.

![]() The founders were generous when they assumed that the nation they were establishing would be able to master the challenges of self-government. But with each month under the current administration we are forced to acknowledge the limits of their work on the Constitution, which assumed the public was smart enough to select ethical leaders. To be sure, there were skeptics, including Hamilton, Madison and Adams. Madison assumed the need for “sufficient virtue among men for self-government.” And Adams felt the Constitution would work only with “moral and religious people.” Given the natural constraints against seeing far into the future, they perhaps did the best they could. But it seems like the document is full of holes, with clear evidence now that a rogue President will pay a minimal price for going beyond its vague constraints.

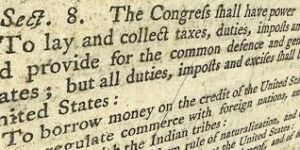

The founders were generous when they assumed that the nation they were establishing would be able to master the challenges of self-government. But with each month under the current administration we are forced to acknowledge the limits of their work on the Constitution, which assumed the public was smart enough to select ethical leaders. To be sure, there were skeptics, including Hamilton, Madison and Adams. Madison assumed the need for “sufficient virtue among men for self-government.” And Adams felt the Constitution would work only with “moral and religious people.” Given the natural constraints against seeing far into the future, they perhaps did the best they could. But it seems like the document is full of holes, with clear evidence now that a rogue President will pay a minimal price for going beyond its vague constraints.

The quaint part of this history is that all the founders were concerned about setting up a monarchy. Clearly, the constitution has prevented such an outcome. We have many levels of courts that can delay or derail some actions of a president. But useful enforcement mechanisms that could have been written into the document were not, allowing, for example, the current problem of the wholesale takeover of the Department of Justice to enforce personal grievances and to ignore illegal presidential actions.

In our current situation the unlawful Executive Orders of Donald Trump are many, including impounding funds already approved by Congress, imposing tariffs without review, destroying portions of the White House without proper vetting, using his office to enrich his family, denying immigrants even minimal rights, interfering with university affairs, withholding federal funds from red states, violating existing treaties, and browbeating professionals like reporters and attorneys into silence. I am no constitutional expert, but it is obvious that most of the policing and enforcement functions in our time have been usurped by the President and his mostly unqualified cabinet officers.

In our current situation the unlawful Executive Orders of Donald Trump are many, including impounding funds already approved by Congress, imposing tariffs without review, destroying portions of the White House without proper vetting, using his office to enrich his family, denying immigrants even minimal rights, interfering with university affairs, withholding federal funds from red states, violating existing treaties, and browbeating professionals like reporters and attorneys into silence. I am no constitutional expert, but it is obvious that most of the policing and enforcement functions in our time have been usurped by the President and his mostly unqualified cabinet officers.

These violations exist in parallel with unwritten but clearly known norms for conducting the nation’s business at home and abroad. Presidents have always taken care to move beyond partisanship to celebrate  charities, cities, arts groups and immigrant communities. Instead, what little rhetorical energy that remains is used for personal verbal abuse, taunts aimed at our former Canadian Allies, and senseless indictments of countless others actually doing constructive work. There is little time or space devoted to appealing to our best inclusive values. Instead, the abandonment of this custom has pulled down the edifice of American civic discourse.

charities, cities, arts groups and immigrant communities. Instead, what little rhetorical energy that remains is used for personal verbal abuse, taunts aimed at our former Canadian Allies, and senseless indictments of countless others actually doing constructive work. There is little time or space devoted to appealing to our best inclusive values. Instead, the abandonment of this custom has pulled down the edifice of American civic discourse.

If given the chance, the founders of the nation could rightly put the blame back on us. At the 1787 Constitutional Convention Franklin offered the caution that his peers have fashioned a new republic, “if you can keep it.” He and others knew that political factions that seem baked into any society can devolve into crude motives and actions. They should have acted to curb these possibilities.

Perhaps a continent-nation is too big to be a single entity to be effectively governed from a centralized government. The founders were dealing with just 13 colonies. And, as the British writer Simon Jenkins has recently noted, we often miss the point that the founders talked about the “United States.” The “s” matters. No one anticipates a mostly “united state,” at least in the way that could perhaps happen in a nation of seven or eight million. They assumed a fair degree of local autonomy, which we tend to overlook because our media is cross-regional, and because a progressive view of nationhood favors the idea of federalism. It is instructive that even the EU and Canada struggle at times to establish cross-border or cross-provincial norms that are binding on all.

Perhaps a continent-nation is too big to be a single entity to be effectively governed from a centralized government. The founders were dealing with just 13 colonies. And, as the British writer Simon Jenkins has recently noted, we often miss the point that the founders talked about the “United States.” The “s” matters. No one anticipates a mostly “united state,” at least in the way that could perhaps happen in a nation of seven or eight million. They assumed a fair degree of local autonomy, which we tend to overlook because our media is cross-regional, and because a progressive view of nationhood favors the idea of federalism. It is instructive that even the EU and Canada struggle at times to establish cross-border or cross-provincial norms that are binding on all.

Our quandary is that constitutional changes are almost impossible to achieve, since they must have sizable majorities of legislatures and states to agree. In addition, we live in an era when citizens can escape news on the nation’s civic affairs by living in media bubbles offering far more escape than information. In the short term, our best hope is the resurrection of the moribund Congress in 2026, which could again exercise the powers given to it under the Constitution’s Article I.

![]()