Place matters a lot in how humans relate. In a welcoming setting we feel comfortable, even as strangers.

The new ‘work at home’ culture that has emerged after Covid has a lot of cultural observers asking questions about how we are coping with this partial shift. Do we feel isolated? Would we willingly go back to pre-pandemic days? Some apparently find the world a bit limited when living and working under the same roof. And the office is not always a remedy. With more colleagues on scattered schedules, traditional work spaces have lost some chances for the kind of amiability that might have existed prior to Covid. Of Course, there are many exceptions. But few would welcome a ten-hour day in the middle of a half empty carrel farm. And not every workplace can be the kind of extended ‘game room’ that the folks working at Pixar seem to enjoy.

Sociologist Ray Oldenburg coined the idea of “the third place” several decades ago to describe a need in people to be out in the world, but without the hierarchies and tensions that often come from homes or offices. Libraries, inviting parks, coffee shops, public lectures, bookstores, bars, and churches are representative examples. Oldenburg noted that third places needed to be informal and welcoming with “no formal criteria of membership and exclusion.” So, as New York Times journalist Anna Kodé recently noted, an escape to a cozy private club does not meet his standard.

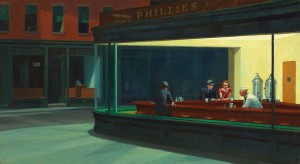

We need third places to fully experience being “of” a place: to feel connected to a community that offers chances for random connections with few requirements. In these spaces with may still be “strangers,” but our simple presence is somehow affirming. Imagine the denizens of Cheers”(1982+) or Friends (1994+) when all were just first-time visitors.

As in most towns and cities, a coffee shop with enough space is a representative case. My little town has a few good examples. My experience is that those lounging on the chairs and sofas are less thirsty than fulfilling a need to be in a common physical space. Many working on their laptops appear to be enacting an adult version of the parallel play of children.

There is an interesting communication dynamic in the act of putting ourselves in the presence of others, but not necessarily interacting with them. Place matters a lot in how humans relate. In a welcoming setting we feel comfortable even as strangers.

The Importance of Partaking

The idea of communication has its root in the Latin verb communicare, which translates as “sharing with another” or “to make common.” But, as silent witnesses, are we really  connecting in a third space? The argument for “yes” is strong. Our bodies and clothing say a lot, mostly that we are part of the tribe. There is also a degree of comfort when entering a welcoming space that is non-threatening. This derives from escaping the usual burden of responding to settings with clear expectations and verbal scripts. Because what we say can unexpectedly boomerang, our presence in a place is usually the additional option of adding our thoughts. An important part of communication is simply being present. What communication theorist John Durham Peters call “partaking” means “taking part in a collective world.” This is much more than an ancillary part of communication; it speaks to our core nature as social creatures.

connecting in a third space? The argument for “yes” is strong. Our bodies and clothing say a lot, mostly that we are part of the tribe. There is also a degree of comfort when entering a welcoming space that is non-threatening. This derives from escaping the usual burden of responding to settings with clear expectations and verbal scripts. Because what we say can unexpectedly boomerang, our presence in a place is usually the additional option of adding our thoughts. An important part of communication is simply being present. What communication theorist John Durham Peters call “partaking” means “taking part in a collective world.” This is much more than an ancillary part of communication; it speaks to our core nature as social creatures.

Many theorists have paired Oldenburg’s idea with the work of social scientist Robert Putnam, who has argued that we live in an era where old and durable affiliations have withered. He lamented the decline of trade unions, granges, small museums, community service groups, church-supported activities and even bowling lanes, which were at a low ebb when the book was written. In Bowling Alone (2000) he noted that, even with increasing urbanization, we seem more isolated. More entertainment is produced exclusively with home consumption in mind. And, of course, the non-games side of the internet atomizes experience with only intermittent real-time interaction. (Texting resembles signaling, setting the bar too low to be included as rich human communication.) Some of those civic facilities that remain—school boards, city council meetings, and PTAs—now seem to come with more tensions that can easily shatter the idea that gatherings can nature the individual.

In the best of cases, partaking as communication is affirming because we are noticed and seemingly accepted: a variation of the old aphorism that “80 percent of life is just showing up.”

![]()

The present moment has created more self-isolation than most would like. We know what it means to be alone with one’s own thoughts. Chatter with others may be in short supply. But our consciousness can easily take the chatter inside. We may share a common culture and lineage, and we can build bridges to each other, but can our reservoirs of self-reflection ever be made transparent?

The present moment has created more self-isolation than most would like. We know what it means to be alone with one’s own thoughts. Chatter with others may be in short supply. But our consciousness can easily take the chatter inside. We may share a common culture and lineage, and we can build bridges to each other, but can our reservoirs of self-reflection ever be made transparent?