[A 2016 piece originally titled “Happily Misinformed” cites a feature of our age that seems even more appropriate now than when it was first published. How can we explain people who hold ersatz opinions in contradiction to established facts and evidence? Here’s an updated version of that piece.]

[A 2016 piece originally titled “Happily Misinformed” cites a feature of our age that seems even more appropriate now than when it was first published. How can we explain people who hold ersatz opinions in contradiction to established facts and evidence? Here’s an updated version of that piece.]

In his sobering 1989 study, Democracy Without Citizens, Robert Entman dwells on the irony of living in an information-rich age among uninformed citizens. There is a rich paradox to a culture where most members have a vast virtual library available on their computer, yet would struggle to pass a third grade civics test. According to the Annenberg Public Policy Center, only one in three Americans can name our three branches of government. And only the same lone third could identify the party that controls each of the two houses of Congress. Fully a fifth of their sample thought that close decisions in the Supreme Court were sent to Congress to be settled.

Add in the dismal results of map literacy tests of high school and college students (“Where is Africa?,” “Identify your city on this map”), and we have just a few markers of a failed information society.

As Entman noted, “computer and communication technology has enhanced the ability to obtain and transmit information rapidly and accurately,” but “the public’s knowledge of facts or reality have actually deteriorated.” The result is “more political fantasy and myth transmitted by the very same news media.” We seem to live comfortably without even elementary understandings of forces that effect our lives.

This condition is sometimes identified as a feature of the Dunning-Kruger effect, a peculiarly distressing form of functional ignorance observed by two Cornell psychologists. Their basic idea is that many of us seem not to be bothered by what we don’t know, producing a level of ignorance that allows us to overestimate our knowledge. Dunning and Kruger found that “incompetent” individuals (those falling into the lowest quartile of knowledge on a subject) often failed to recognize their own lack of skill, failed to recognize the extent to which they were misinformed, and did not to accurately gauge the skills of others. In short, a person’s ignorance can actually increase rather than decrease their informational confidence. If you have an Uncle Fred who is certain that former President Obama is a Muslim born in Kenya, or that vaccines cause autism, you have an idea of what kind of willful ignorance this represents.

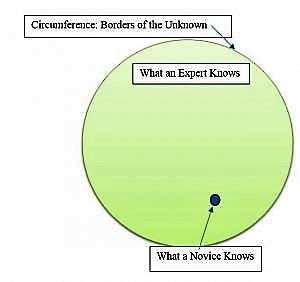

Think of this pattern in an inverted sense: from the perspective of individuals who truly know what they are talking about. Even for the well-informed, the more they know about a subject, the larger the circumference of the boundaries that delineate the unknown. It takes considerable knowledge to know what you don’t know. That’s why those who have mastered a subject area are often the most humble about their expertise: their expanded understanding of a field give them a sense of the many areas that remain to be explored.

All of this makes listening to the truly ignorant a measure of our forbearance. We are left to vicariously know the shame of someone who is not smart enough to feel it. As with our President, we wonder why he doesn’t feel more embarrassment for his exaggerations and falsehoods. Has he never really read about the substantive policy accomplishments of F.D.R (the FDIC, Social Security) or L.B.J.? (successful anti-poverty programs, the Civil Rights acts of 1964 or 1965). Can slapping on tariffs for goods and subverting long-standing values of equality and fairness be enough to count as great leadership?

The Dunning-Kruger Effect shows it self in other ways as well. A key factor is our distraction by all forms of media—everything from texting to empty-headed television programming—that leaves us with little available time to be contributing members of the community. When the norm is checking our phones over 100 times a day, we have perhaps reached a tipping point where we have no time or energy left to fill in our own informational black holes.

The idea of citizenship should mean more. In this coming election cycle it’s worth remembering that nearly half of eligible voters will probably not bother to vote. And even more will have no interest in learning about president and legislative candidates. Worst still, this is all happening at a time when candidates have been captured by a reality-show logic that substitutes melodrama for more sober discussions of how they intend to govern. Put it altogether, and its clear that too many of us don’t notice that we are engrossed with a sideshow rather than the main event.

![]()