Selling things or promises is our common national heritage, usually featuring a mixture of shameless persuasion and outright ‘cons.’

Most cultural observers note that Americans these days are perhaps better at selling stuff than making it. It’s an understatement to note that we have a knack for marketing services and wares to each other. Our economy is largely propelled by consumption. And while we can still design elegant products like phones, cars and electronics, many if not most of their parts are made elsewhere. On the other hand, selling them is something we still do well, sometimes too well.

Even Americans with modest incomes are drowning in stuff. There’s a store and product for nearly every budget. One sign is the spread of the American idea of franchise stores, with familiar brands now in every corner of the world. Think of McDonalds or Marriott. Another sign is the common problem families face in finding places to store all of the things they have accumulated. In most neighborhoods garages originally built to hold cars are now used for storage. Especially in the West, the family car is usually relegated to the driveway.

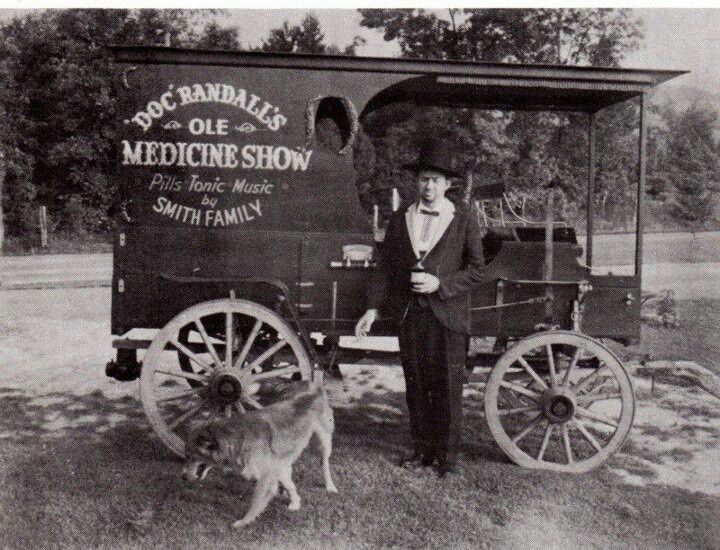

Cultural historian Daniel Boorstin was among the first to offer a seminal account of the typical American “go getter” continually “on the make.” (The Americans: The Democratic Experience, 1973). Our common heritage is selling and buying medicines, household products and goods that promise happiness. CNBC’s popular reality show Shark Tank continues the trend and represents it in miniature. It features investors with cash whose hearts quicken when they hear a good sales ‘pitch’, often from strivers who have more optimism than judgement. Some may be natural entrepreneurs. But it’s equally likely that others are attracted to the idea of making a pitch as a pathway to celebrity. Everyone knows the story of actress Lori Loughlin’s daughter, Jade, who used her ill-gained admission to the University of Southern California not to become a serious student, but because of the ego-boost of being a social media “influencer” on campus. We can also look to the current President as an example the ultimate “man on the make.” Given recent evidence of massive business losses over the years, Donald Trump appears to have little talent for anything except selling his “brand.” In this sense, his ‘cons’ make him less of an outlier then we might think.

![]()

The pitch is the thing; the product, not so much.

Observing this long-running streak from the communication side makes it plain that little has changed since the days of P. T. Barnum, or the medicine shows that once toured the country. Today, many students beginning their college careers are still enamored with the apparatus of selling as represented by ad agencies, public relations firms, social media, electronic media and other ways to attract willing buyers. In my own institution the fields of marketing, sales and communication studies easily attract more students than fields like engineering or education. And while a professor of persuasion should delight in seeing communication as a subject of special interest, it’s apparent that this fascination often comes with less thought in what the content of a given message should be. The pitch is the thing; the product, not so much. And so the campus television studio remains high on the list of places for future communication students to visit. The excellent library can wait.

Consider another case. A recent New York Times article described the rising popularity of entrepreneurial summer camps around the country. Parents can now enroll their eight-year-olds for weeks of immersion in the business world. Highlights typically include stops at a “personal branding station,” in addition to the chance for these youngsters to make their own television commercials for products they will presumably think up later. If their fantasies eventually come true, they may design a campaign around some plastic thing they can pitch to the rest of us as a product “as seen on TV.” The American love affair with selling continues even in the pristine woods and away from our screens.

![]()