Arguably, some of the best forewarnings have come from the British, even in the film Love Actually (2003), where the PM is none too happy with the bullying of his American counterpart.

There is no question that Hollywood warrants its old label as a home of escapist entertainment. But it is also true that there is a growing list of mainstream films offering narratives about the devolution of American political life. Most were first presented as fiction; but hindsight makes some remarkably prescient. These are films plotted around acts of political corruption, deception or exploitative media. Who knew that we should have paid closer attention?

Overcoming studio timidity was never been easy. The cautionary Vietnam fable M*A*S*H (1970) was shot by director Robert Altman in a California state park, away from the prying eyes of nervous Fox executives. Even so, the studio demanded that the film must appear to be about the politically safer Korean War.

The most interesting films include plot lines that anticipate our current moment. For example, in The Manchurian Candidate (1962) propagandists from China and the Soviet Union brainwash a veteran in an effort to have him subvert the United States government. The idea of Communist brainwashing has never been very convincing. But the fact that we have a President seemingly in the thrall of the heirs to the Soviet Union seems like a fantasy that has become uncomfortably real.

Some films are reminders that Americans are easy marks for cynical populists.

There are also a number of films that suggest how easy it can be for an empty vessel of a leader to attract the support of audiences short on reasoning but ready to accept simple-minded bromides. Budd Schulberg’s A Face in the Crowd (1952) suggests that fame can be easily manufactured and sold to ordinary citizens. It’s emphasis on the susceptibility of media audiences is mirrored in other iconic films like writer Paddy Chayefsky’s Network (1976), or All the King’s Men (1949), based on a Pulitzer-winning book by Robert Penn Warren. The latter film is an extended riff on a figure like Louisiana Governor Huey P. Long, a populist demagogue we sells a stream of lies to a clueless public. Depending on the person, films can “mean” many things. For me, Warren’s character of Willie Stark and Network’s Howard Beale are reminders that many of us are easy marks for cynical populists.

Of course, the corruption that may come with power was a theme familiar to Shakespeare’s audiences. It also fascinated film legend Orson Welles, who put the abuse of authority front and center in the form of corrupt police captain Hank Quinlan in A Touch of Evil (1958). And there’s also the ruthless Hearst-like newspaper magnate in Citizen Kane (1941), who had his own seaside Mar-a-lago.

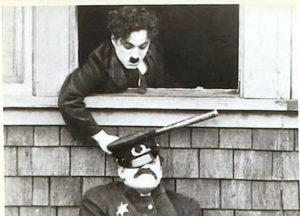

Even Charlie Chaplin gave  us reasons to be wary about the abuse of power, consistently using the gentle figure of the Tramp to deflate the police and the pompous. His pattern of mocking leaders is carried on by a handful of late-night television hosts, in sharp contrast to talk radio’s continuing love of reactionary politics.

us reasons to be wary about the abuse of power, consistently using the gentle figure of the Tramp to deflate the police and the pompous. His pattern of mocking leaders is carried on by a handful of late-night television hosts, in sharp contrast to talk radio’s continuing love of reactionary politics.

Viewers of films about the McCarthy era may also see the coming pattern of the current president to scapegoat problems to immigrants, Mexicans, China or even NFL players. The Wisconsin senator’s bludgeon was anti-communism. His penchant for making baseless accusations against whole categories of Americans is well-represented in Bryan Cranston’s 2015 portrayal of blacklisted writer Dalton Trumbo. This accustory strain in American politics has its own fascinating lineage of sobering Hollywood jeremiads, ranging from a film version of Arthur’s Miller’s The Crucible (1996) to the Edward R. Murrow biopic, Good Night and Good Luck (2005).

More recently, the best forewarnings on film have come from the British. In the surprising case of the otherwise negligible Love Actually (2003), a perfect rebuke is directed to a bullying American President. Hugh Grant is the PM, and is none too happy with the high-handedness and arrogance of his American counterpart: words that would work equally well for the embattled Theresa May.

In the recent past, BBC Films and the U.K. Film Council win the honors for confronting the problem of governments who have gone of the rails. In the Loop (2009) is played by Tom Hollander and Peter Capaldi as farce, but seems close to the truth in displaying the twin challenges of bad foreign policy (i.e., the invasion of Iraq) pursued by inept bureaucracies. James Gandolfini is a cautious American General who is no match for the spin doctors in Washington and London that are planning a disastrous joint invasion. In The Loop is a good representation of contemporary suspicions of political discourse, where the energies put into defending policies come prior to determining their basic soundness. What was British farce in 2009 is now evident in the prevarications of official Washington.

![]()

Top Image: Universal Pictures