It is not enough for a thinking adult to remain captive to the highly corrupted spaces of video fantasists.

With media such as YouTube, we have reached a point where the presumption going forward will have to be that the content is fake until it is verified. More and more images and audio are A.I. fabrications.

Last week I was briefly taken in by the YouTube post, since taken down by the platform, that had columnist George Will describing a supposedly sudden transformation within the Republican Congressional caucus. He described their separation from President Trump, and even the possibility of using the 25th Amendment to remove the President from office. The video looked like Will and more or less duplicated his usually clipped cadences.

The first clue that all might not be what it seems was the source, which was not his newspaper, The Washington Post, but some sort of A.I. group called “Inside the Union.” A second was that the words put into Will’s mouth were not quite what he would use at this moment in time. Only a “synthetic content” flag visible for a short time in the corner of the video indicated that it is an A.I. fabrication.

My attention was initially heightened because I hoped the sudden report might be true. Alas, no one else at the AP, the New York Times, or The Wall Street Journal was reporting anything like this supposed GOP insurrection. Clearly Mr. Will had become an unwilling avatar for someone else’s political agenda.

![]()

Tech leaders who present themselves as in the forefront of the race to the future haven’t even left the starting blocks in terms of controlling the veracity of their offerings.

As we know, A.I. technology is capable of more convincing fakes. It was only a matter of time until fake news would become ubiquitous across the political spectrum. As noted in an earlier post, we may be OK with images of a cat minding the fry grill at McDonalds. The joke is obvious. But we should be on guard when the likeness of a person with a curated reputation is hijacked in complete defiance of what they actually believe. Elon Musk’s Grok image generator has similarly been used repeatedly to create false and malicious images that can end up on other sites. And, obviously, X, YouTube and other platforms are not immune. Tech leaders who like to present themselves as in the forefront in the race to the future haven’t even left the starting blocks when it comes to controlling the veracity of their offerings.

A person’s reputation for accuracy may be the most important character trait they have. Routine fakery should not be allowed to rob them of that. Whether we want to or not, all of us are going to have learn to do what journalists and prosecutors do to test the credibility of their sources.

A person’s reputation for accuracy may be the most important character trait they have. Routine fakery should not be allowed to rob them of that. Whether we want to or not, all of us are going to have learn to do what journalists and prosecutors do to test the credibility of their sources.

Their method is sometimes called “triangulation,” where a given story is checked against other sources known for credible reporting. To be sure, this takes a little bit of time. As landmark movies about journalism remind us, investigative reporters usually need two or three sources to confirm that a narrative is accurate. Think of All the President’s Men (1976), Shattered Glass (2003) or Spotlight (2015). The related and honorable practice of fact-checking is also a tradition at major news outlets and legendary at The New Yorker. In addition, triangulation usually means getting out of the video media bubble and moving on to more reliable human and print sources. It is not enough for a thinking adult to remain in the highly corrupted spaces of video fantasists.

All of this is a reminder schools should be regularly teaching some version of a course in Evidence and sources in the middle and upper grades. Every citizen needs to know what high and low credibility looks like, as well as some of the basic rules of evidence, Navigating the swamps of digital media where anything can be faked is going to require cognitive screening skills that will have to become second nature.

All of this is a reminder schools should be regularly teaching some version of a course in Evidence and sources in the middle and upper grades. Every citizen needs to know what high and low credibility looks like, as well as some of the basic rules of evidence, Navigating the swamps of digital media where anything can be faked is going to require cognitive screening skills that will have to become second nature.

Media theorist Marshall McLuhan reminded us that one medium is not easily translated into another.

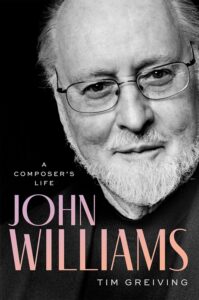

Media theorist Marshall McLuhan reminded us that one medium is not easily translated into another.  An easy answer is that words about musical form can enhance what we are hearing. Libraries of words about music can be vast and maybe compelling and revealing. That is surely what Leonared Bernstein thought in his famous 1973 Norton Lectures at Harvard. If there ever was a valiant effort to marry musical sounds with their meanings, these six lectures are it. It is no surprise that Bernstein leans heavily on what may be the slight cheat of using generative linquistics to bring its music to life. It suggests that music is just another “language:” a common but perhaps limiting metaphor that needs a harder look.

An easy answer is that words about musical form can enhance what we are hearing. Libraries of words about music can be vast and maybe compelling and revealing. That is surely what Leonared Bernstein thought in his famous 1973 Norton Lectures at Harvard. If there ever was a valiant effort to marry musical sounds with their meanings, these six lectures are it. It is no surprise that Bernstein leans heavily on what may be the slight cheat of using generative linquistics to bring its music to life. It suggests that music is just another “language:” a common but perhaps limiting metaphor that needs a harder look.