- Negotiating Table Inside the Joint Security Area Separating North from South Korea

Photo: South Korean Government

Seating arrangements subtly govern how individuals are likely to respond. Some arrangements encourage interaction. Others discourage it.

Movie stars, producers and other supplicants summoned to the office of Louis B. Mayer in Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer’s complex in Culver City often remember their first impression. Mayer was the very definition of a movie mogul in charge of the studio that defined Hollywood’s “golden age.” Befitting his place at the center of a industry that worshiped visual impressions, visitors passed through massive carved doors to enter his inner sanctum. Then it was another 60-foot walk between white leather walls to his massive ship of a desk at the far end of the room. The short man who gave us The Wizard of Oz apparently liked the idea inscrutability. All of the office trappings were meant to remind a visitor that any decision that would come out of the meeting was likely to be exactly what Mayer wanted.

Studies of non-verbal elements of communication include seating as a crucial variable. Seating arrangements subtly govern how individuals are likely to respond. Some arrangements encourage interaction. Others discourage it. The arrangement of furniture for a gathering is nearly always consequential as an important communication variable.

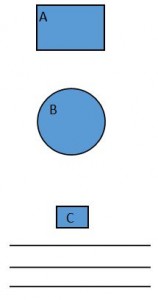

Here’s the drill on what to consider. For smaller groups a round table (B) is perfect for encouraging and even equalizing participation. No one has a power advantage by virtue of their place. Any leader is visually an equal among peers. Note, too, that at a round table everyone has at least some possibility of eye contact with others: a key variable that helps to encourage participation from the naturally introverted. The downside is that anyone around the table can use even minimal facial cues to undermine a speaker’s point. We’ve all probably used a frown worthy of an M-G-M closeup to telegraph our displeasure at a leader’s point. For good reasons the round table model needs a genuine commitment from all participants to work in common cause.

Here’s the drill on what to consider. For smaller groups a round table (B) is perfect for encouraging and even equalizing participation. No one has a power advantage by virtue of their place. Any leader is visually an equal among peers. Note, too, that at a round table everyone has at least some possibility of eye contact with others: a key variable that helps to encourage participation from the naturally introverted. The downside is that anyone around the table can use even minimal facial cues to undermine a speaker’s point. We’ve all probably used a frown worthy of an M-G-M closeup to telegraph our displeasure at a leader’s point. For good reasons the round table model needs a genuine commitment from all participants to work in common cause.

A rectangular table (A) is more likely to distribute advantages to some and limit participation by others. In a typical rectangle the power positions are at the both ends. From these vantage points it is easier to be seen and to control the participation of others. And so we may be able to push “reluctants” out of their shells by placing them in these positions (even though introverts will often resist being placed at the head of a table). Conversely, “dominators” will have a harder time controlling a discussion if they sit on one of the long sides of the table on one of the corners. Those positions make it difficult to have eye contact with some participants, especially those on the same side of the table.

A rectangular table is also the preferred arrangement when the objective is to carry on two-sided talks. Labor-management negotiations, meetings in the “dead zone” between North and South Korea, and other situations where there are distinct “sides” are visually maintained this face-off arrangement.

Interestingly, in the White House Cabinet Room a President usually sits along one side of the long oval table, not at the head. But the oval preserves some of the virtues of a round table. And it looks good in photo ops to have the president appear to be one among others. By contrast, with the serious business of discussions in the basement Situation Room, the President is usually at the head.

Rows of chairs facing a single source, as in the seating pattern represented in the above diagram as “C” lends itself to giving one person in front maximum control. It’s an obvious point, but for an interesting reason. When a member of the audience has only the back of another’s head in their foreground view they have little choice but to give more attention to the presenter, even when that person is some distance away. Audience members are essentially denied most of the non-verbal facial cues that other members can give that would undermine their faith in the presenter’s message. So arena or “classroom” styles of seating give all the advantages to the single source at the front.

We tend to forget that hundreds died in Vietnam over the Winter of 1968 while talks scheduled to begin in Paris were stalled. The issue? The shape of the negotiating table. Were these essentially four-party or really two-party negotiations? Only putting a round table in between two rectangular tables radiating out from the center finally settled the issue. The arrangement saved the South Vietnamese from having to deal with the Vietcong as an equal negotiating partner. Seating can matter that much.

Comment at woodward@tcnj.edu