Little wonder that noise is the most common complaint about eateries of all sorts.

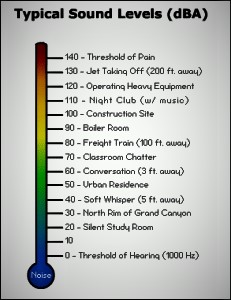

It is not uncommon for restaurant critics to write reviews pointing out sound levels in even expensive establishments that are “abusive” and “overpowering.” A reasonable noise level at a restaurant should be about 65 decibels. But many easily top 85 or higher. (This measurement scale is logarithmic; every few decibel increases roughly doubles perceived loudness.) Little wonder noise is the most common complaint about establishments of all sorts. Then there is often music thrown in to add to the aural chaos. City retail rents tend to dictate many tables in small rooms. Add in the bar culture in some watering holes and you’ve come close to replicating the sound energy on an airport runway.

This is not just a big city problem. Eateries in my small-town generally have the same issue. More tables potentially increases the take for an establishment on a good night, not to mention that diners almost on top of each other get the incidental chance to try out a neighboring meal.

This is not just a big city problem. Eateries in my small-town generally have the same issue. More tables potentially increases the take for an establishment on a good night, not to mention that diners almost on top of each other get the incidental chance to try out a neighboring meal.

For all of this we have a peculiar solution from former restaurant critic Pete Wells, suggesting Apple’s AirPods Pro 2. These earbuds act as “over-the-counter hearing aids for mild to moderate hearing loss, adjustable to your own ears.” His recommendation is based on the “Conversation Boost” mode, which “uses directional microphones to isolate and amplify voices that are directly in front of the listener. Ambient Noise Reduction dampens sound coming from other angles.” The irony, of course, is that the use of these amounts to taking a tiny public address system with you to dinner so you can hear the person at the same table. Count that as another weird 21st Century fix. The A.I. image at the top shows what this might look like.

A continuous piling on of high decibels can leave a person at risk of cardiovascular disease. That’s a considerable distance from the 120 decibels that can produce permanent hearing loss: incidentally, a real risk for kitchen workers and musicians of all sorts. Even so, many of us don’t notice the problem. We are used to moving through environments that push at the margins of aural comfort. Some of us are natural stoics, bearing the burden until it is mentioned by others. This is one reason excessive sound volume is a contributor to stress. As ambient sound turns into a roar it stretches the natural elasticity of our patience. In the end, we feel drained and fatigued without exactly knowing why.

My advice for a reasonable shot at an evening when you can hear your dinner companions:

- Avoid restaurants known for hosting big groups and celebrations. Crowds of people at one table tend to encourage others to talk louder to be heard. If you end up seated next to a wedding party or birthday celebration, you are probably in for a night of lip reading.

- Dine out mid-week more than weekends when restaurants are less crowded.

- Think of “old school” restaurants that are elaborately decorated or filled with booths. High ceilings, carpet, and the luxury of space between tables that can significantly lower decibel levels.

- Though they are usually not cuisine hotspots, hotel dining rooms are usually a spacious refuge.

- Consider take out.