It is worth considering the idea that large nations may be too big to fail, but also too big to thrive as open societies.

A phrase frequently heard during the financial meltdown of 2008 was that certain banks were “too big to fail.” It is often the case that we equate the control of vast spaces or resources as a sign of an institution’s preeminence in the culture. We can’t do without them. But when looking at sovereign nations, I’m beginning to think that the reverse is true. The vast Soviet state with 11 time zones and 15 republics failed in part because its leaders could not effectively govern all of the diverse factions bridging Europe and Asia. Vladivostok, located in the Russian Far East, is over 5500 miles from Moscow. Similarly, before the United States gave it new reasons to care, Canada had struggled to unify its vast provinces and native groups to form a coherent nation. The U.S. has inadvertently helped Canadian citizens unify against their sour neighbor to the south. Ditto for China, which needs its rising wealth to keep very different areas like Hong Kong and Tibet under their thumb. Lhasa in Tibet is 3500 miles from Beijing, and holds on to some autonomy. That’s a great distance, but shorter than the space between Honolulu and Washington, D.C. (approximately 5,000 miles). Distance is obviously more easily bridged in the digital age. But as the old Mason-Dixon line reminds us, it is not insignificant as a key variable for achieving a degree of national cohesion.

As a thought experiment, it is worth considering the thesis that large states may appear to be too big to fail, but they may also be too big to thrive as open societies. No one living in one of the geographical giants with huge land masses and understandably diverse populations can call them fully “unified.” This seems so obvious now. Though pollsters caution against assuming that the American population is as polarized as its current politics, it is still clear that regional differences have turned into regional antagonisms that weaken the chances to establish a good society.

As a thought experiment, it is worth considering the thesis that large states may appear to be too big to fail, but they may also be too big to thrive as open societies. No one living in one of the geographical giants with huge land masses and understandably diverse populations can call them fully “unified.” This seems so obvious now. Though pollsters caution against assuming that the American population is as polarized as its current politics, it is still clear that regional differences have turned into regional antagonisms that weaken the chances to establish a good society.

Politically, Vermont does not look like Florida. Among others, Senator Bernie Sanders seems like a natural representative of the Green Mountain State. Some political norms in other northern tier states would hardly be recognized by the government now sitting in southern capitols like Tallahassee. Reproductive freedom for women, control of hiring and curricula in some universities, book banning, official support for child vaccines and social services are vastly different. For example, in terms of money spent per child for K-12 public education, New Jersey and Massachusetts look more like Sweden ($15,000) than some of the southern states. In 2020 New Jersey spent over twice as much per student ($20,600) than Florida ($9,937). This can be taken as only a rough indicator, but it is suggestive of the yawning differences that exist in populations sharing the same national leadership and ostensibly the same values. One expects that Norwegians and Germans less than 800 miles apart do not experience the same span in civil norms as Russia or the U.S., though their citizens have their differences. To put it a different way, nations bridge a vast continent are arguably a long way from whatever we mean by a coherent society.

Aristotle estimated that size of an ideal polity would be the number of people who could know most of their fellow citizens. The city-states in his time numbered from 500 to 5000 citizens. In pre-electric times a community was contiguous rather than dispersed; members could more readily rub shoulders with their fellow citizens. To be sure, size is partly a limitation that belongs to another époque. But, in general terms, a nation that is larger and much more diverse is likely to see less opportunities for social cohesion: even more so in the era of newly fragmented media. For example, in 2006 less than half of American young adults could identify Ohio on a national map.

Aristotle estimated that size of an ideal polity would be the number of people who could know most of their fellow citizens. The city-states in his time numbered from 500 to 5000 citizens. In pre-electric times a community was contiguous rather than dispersed; members could more readily rub shoulders with their fellow citizens. To be sure, size is partly a limitation that belongs to another époque. But, in general terms, a nation that is larger and much more diverse is likely to see less opportunities for social cohesion: even more so in the era of newly fragmented media. For example, in 2006 less than half of American young adults could identify Ohio on a national map.

Questioning Ethnic Variety in the Same Sovereign State

Based on recent elections, even tolerant Scandinavians seem to be coming to the belief that multiculturalism has its limits. And there are fewer states that are anything like the monoculture of Japan. That may be a good thing, building on the countervailing idea that synergies created by different cultural traditions enrich a culture. But smaller European states are collectively agonizing over when immigration undermines their cornerstone values. However it manages, we now understand how lucky a nation is to have leaders and systems that can hold on to strong diversity as a foundational idea. The way things are going, the French may want their harbor statue back.

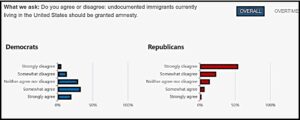

The United States is again (always?) in an era when even core values are disputed, when subcultures with distinct norms become alien and hostile to each other. Consider again additional north-south differences. Northern residents are sometimes reminded that they get less federal money than they contribute in taxes. In the case of New Jersey, 91 cents on every tax dollar goes to federal coffers. By comparison some southern states may receive over two dollars in aid for every dollar sent. As to specific issues, members of the dominant GOP in many of the southern states see real dangers in the presence of undocumented immigrants, most of whom who are reliable workers doing jobs in their communities that no one else wants. As indicated in the chart below, by a wide margin most in the GOP do not want an amnesty extended to them, with brutal ICE arrests as one consequence.

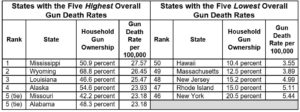

With regard to gun ownership and its corollary of gun deaths, there is again a sharp regional difference, with most of the states with the lowest rates of gun ownership and gun deaths not so coincidently in a contiguous corner of the east coast. The deadliest areas per capita include Wyoming and Alaska, but otherwise stretch along the southern tier of the nation. Again, attitudes on some Issues generally align with particular regions.

We are obviously describing big entities that must include scores of exceptions, such as the anomaly of blue cities in red states. And there is the natural variability of individual attitudes everywhere; no two people think or act alike. But the overall point still has merit. Sovereign regions would seem to have a better chance of converting themselves into successful civil societies than those which lack the will to build bridges to citizens considered social outliers.

![]()

We like to share the fiction that we are “a people,” but it is obviously a rhetorical covering for a far more varied collection of individuals.

We like to share the fiction that we are “a people,” but it is obviously a rhetorical covering for a far more varied collection of individuals.